Team:NTNU Trondheim/Description

Project Description

Background

We have chosen to do a project related to diabetes, a group of metabolic diseases caused by a deficiency of the hormone insulin and/or a decreased response to the insulin produced in the body (diabetes type 1 and 2, respectively). This leads to a high and unstable blood glucose level, as the body needs insulin to get glucose from the blood into the cells to use as energy. (WHO, 2015)

A failure to manage the disease can have serious consequences, even death. Over time, diabetes can lead to a higher risk of heart disease and strokes, neuropathy and infections in limbs and subsequent amputations, blindness and kidney failure. Worldwide, an estimated 9% of adults 18 years or older have diabetes. In 2012 alone, 1.5 million deaths were directly caused by diabetes. (WHO, 2015)

In management of diabetes, a healthy lifestyle is very important. For some patients it may be necessary to adjust blood glucose levels (and other risk factors that can damage blood vessels) with insulin injections or antidiabetic drugs as well. Therefore it is important for the patient to measure or meter the blood glucose level following food intake and physical activity. (WHO, 2015)

Motivation

Almost everyone has a family member or a friend who suffers from diabetes, and we thought it would be nice to work on a project that most people can relate to. Most diabetics have to rely on measuring blood glucose levels several times a day, and we want to investigate the possibility of engineering a bacterial glucose sensor that can simplify this task for diabetes patients in the future.

Early on we talked about creating a biosensor, more specifically an efficient glucose sensing system in bacteria (we did not find any papers about such systems of detection). In addition, we wanted to use the cell encapsulation technology developed at NTNU, using the environmentally friendly biomaterial alginate. Brown algae can be found all along the coast of Norway, and it is an abundant natural resource! Our system could have several possible applications, diabetes management being one of them.

We also wanted to try a different model organism than Escherichia coli.

Objectives

- To engineer a novel glucose sensing system in Pseudomonas putida by expressing the red fluorescent protein mCherry upon glucose detection (as a proof of concept).

- To encapsulate the engineered Pseudomonas putida in alginate, and to tailor the capsule properties to best suit our engineered cells and possible applications.

- To improve the Matchmaker website, originally developed by the 2012 NTNU Trondheim team.

- To develop a model of the glucose sensing system.

Methods

Molecular Genetics

Glucose Metabolism in Pseudomonas putida

Glucose, gluconate and 2-ketogluconate are transported into the cell without being modified (Figure 2). In the periplasm, glucose can either be transformed into gluconate and subsequently to 2-ketogluconate or it can pass the inner membrane. Approximately half of glucose in the periplasm is directly channeled into the cytosol. The other half is processed via the 2-Ketogluconate peripheral pathway. Less than 10% of gluconate produced by glucose is directly passing the inner membrane. (del Castillo et al., 2007)

In the cytosol, glucose is transformed via glucokinase (glk) and glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase (zfw) into 6-phosphogluconate. 2-Ketogluconate is modified by 2-ketogluconate kinase (kguK) and reductase (kguD), which results in 6-phosphogluconate as well. Finally, 6-phosphogluconate is transformed into 2-keto-3-deoxy-6P-gluconate and subsequently cleaved into pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate.(Daddaoua et al., 2009)

The Promoters We Use

There are four operons whose structural genes are directly concerned with the glucose metabolism. All are negatively controlled, two by the repressor PtxS and the other two by HexR.

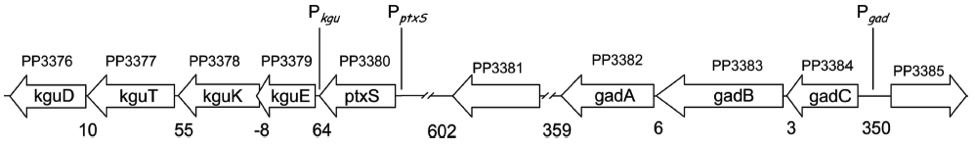

The kgu and gad operons (Figure 3), specifically the promoters Pkgu and Pgad contain the operator sequence for the repressor PtxS. It has a DNA binding site as well as a binding site for 2-Ketogluconate. The ptxR and RNA polymerase binding site of Pkgu and Pgad overlap. Thus, PtxR represses gene expression by means of competing with the RNA polymerase for binding. In the presence of 2-Ketogluconate, PtxS changes its conformation and dissociates from the DNA. The RNA polymerase is then able to bind to the DNA and to transcribe the structural genes.

The kgu operon comprises four open reading frames (ORF) coding for kguE, kguK, kguT and kguD (2-ketogluconate epimerase, kinase, transporter and reductase, respectively). The gad operon comprises three ORFs encoding gadC, gadB, and gadA.

The promoters of the edd and zwf operon (Figure 4) contain the operator sequence for the repressor HexR. It is monomeric in solution but assembles to a dimer when binding to DNA. The mechanism of repression is most probably due to inhibition of progression of RNA polymerase. Additionally, HexR has a binding site for 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate (KDPG). In its presence, the dimeric HexR is released from the DNA and transcription can progress.

Besides the edd gene (encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase), the edd operon comprises the genes glk, gltR2 and gltS (encoding glucokinase and proteins of the glucose transport system, respectively). The zwf operon comprises the genes for zwf, pgl and eda, which all are encoding enzymes for the glucose metabolism as well. (Daddaoua et al., 2009)

Our Engineered Plasmid

Subsequently to the respective promoter, our engineered plasmid contains mCherry, a red fluorescent protein. Its excitation maximum is at 584 nm, its emission maximum is at 620 nm (Takara Clontech, 2015). Additionally, the backbone contains KanR (aminoglycoside 3-phosphotransferase), enabling the transformed cell to be resistant against kanamycin (Figure 5).

Cell Encapsulation

Alginate

Alginate

Alginate is a polymeric biomaterial that can be extracted from marine brown algae (e.g. Laminaria hyperborea), or synthesized by some soil bacteria (some Pseudomonas and Azotobacter species). At NTNU, extensive research has been done for decades on alginate and its many applications - it is even considered to be the national molecule of Norway! Alginate is a linear polymer consisting of (1-4)-linked β-D-mannuronate (M) and α-L-guluronate (G) residues (Figure 6). (Draget et al., 2006)

Gelation of Alginate

It is the stretches of G-units that are responsible for gelling of alginate by binding multivalent cations (Draget, 2011).The G-units in alginate exist in the 1C4-conformation, and this makes the glycosidic linkages diaxial. This places the rings almost perpendicular to the chain axis, and results in cavities between two or more aligned chains. Two or more G-blocks aligned selectively bind Ca2+ strongly and form junctions in a gel network (also called the egg-box model, as shown in Figure 7). Stretches in the polymer chains consisting of M-blocks and MG-blocks do not bind Ca2+ strongly. (Smidsrød and Moe, 2008)

Encapsulation method

Alginate capsules can be made by dropping alginate solution into a gelling solution containing CaCl2, where the alginate will gel instantly when it comes in contact with calcium ions. To encapsulate living cells, they can simply be mixed into the alginate solution prior to gelation. As the alginate solution is very viscous, a capsule generator is necessary to achieve small enough capsules (< 1mm).

The high voltage electrostatic capsule generator (made at the Department of Physics, NTNU) enables the production of alginate microcapsules with a narrow size distribution. The capsule diameter depends on several parameters, such as the applied voltage, needle diameter, the distance between the electrodes and the alginate solution flow rate (Strand et al., 2002). We aim to produce capsules with a diameter of ~200 μm.

Modeling

The objective of modeling the glucose-detecting bacterial capsules is to reflect the most important dynamics and features of alginate-encapsulated bacterial glucose sensors. The modeling will assist to answer numerous design questions regarding genetic circuits, capsule geometric and physical properties, bacterial density, and predict the performance of the glucose sensor.

Agent-based modeling is being conducted to reflect the complexity of the developed system. This approach allows the integration of genetic networks, multiple-physics, growth models, intricate tri-dimensional boundary conditions. The outcomes of the model will be used to assist in design decisions and will be compared with experimental results. Finally, a general analytical and computational framework for bacteria encapsulation will stem from this project.

iGEM Matchmaker

The iGEM Matchmaker Tool is a website developed by the 2012 NTNU Trondheim team to make it easy for iGEM teams to collaborate and assist each other. The website has been positively received by the iGEM community in the past years. In 2015, the NTNU Trondheim team has decided to deploy and enhance the existing tool focusing on usability, data mining algorithms, technical uphaul, documentation, and open source practices.

References

TAKARA CLONTECH. 2015. mCherry Fluorescent Protein [Online]. Available: http://www.clontech.com/US/Products/Fluorescent_Proteins_and_Reporters/Fluorescent_Proteins_by_Name/mCherry_Fluorescent_Protein [Accessed July 13th 2015].

DADDAOUA, A., KRELL, T., ALFONSO, C., MOREL, B. & RAMOS, J.-L. 2010. Compartmentalized Glucose Metabolism in Pseudomonas putida Is Controlled by the PtxS Repressor. Journal of Bacteriology, 192, 4357-4366.

DADDAOUA, A., KRELL, T. & RAMOS, J.-L. 2009. Regulation of Glucose Metabolism in Pseudomonas: The Phosphorylative Branch and Entner-Doudoroff Enzymes are Regulated by a Repressor Containing a Sugar Iisomerase Domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284, 21360-21368.

DEL CASTILLO, T., RAMOS, J. L., RODRÍGUEZ-HERVA, J. J., FUHRER, T., SAUER, U. & DUQUE, E. 2007. Convergent Peripheral Pathways Catalyze Initial Glucose Catabolism in Pseudomonas putida: Genomic and Flux Analysis. Journal of Bacteriology, 189, 5142-5152.

DRAGET, K. I. 2011. Oligomers: Just background noise or as functional elements in structured biopolymer systems? Food Hydrocolloids, 25, 1963-1965.

DRAGET, K. I., MOE, S. T., SKJÅK-BRÆK, G. & SMIDSRØD, O. 2006. Alginates. In: STEPHEN, A. M., PHILLIPS, G. O. & WILLIAMS, P. A. (eds.) Food polysaccharides and their applications. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC/Taylor & Francis.

SMIDSRØD, O. & MOE, S. T. 2008. Biopolymer chemistry, Trondheim, Tapir Academic Press.

STRAND, B. L., GÅSERØD, O., KULSENG, B., ESPEVIK, T. & SKJÅK-BRÆK, G. 2002. Alginate-polylysine-alginate microcapsules: effect of size reduction on capsule properties. J Microencapsul, 19, 615-30.

WHO. 2015. Diabetes [Online]. Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ [Accessed July 15th 2015].