Difference between revisions of "Template:Team:TU Eindhoven/Design HTML"

Jan Willem (Talk | contribs) |

Jan Willem (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | <h1> | + | <h1 id="h1-1"> |

Introduction - A Universal Biosensor | Introduction - A Universal Biosensor | ||

</h1> | </h1> | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

| − | <h1> | + | <h1 id="h1-2"> |

The Recognition Element – Aptamers | The Recognition Element – Aptamers | ||

</h1> | </h1> | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | <h1> | + | <h1 id="h1-3"> |

The Scaffold - OmpX | The Scaffold - OmpX | ||

</h1> | </h1> | ||

| Line 302: | Line 302: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | <h1> | + | <h1 id="h1-4"> |

The Signaling Components - NanoLuc & Neongreen | The Signaling Components - NanoLuc & Neongreen | ||

</h1> | </h1> | ||

Revision as of 11:40, 10 August 2015

Introduction - A Universal Biosensor

With today’s technology and knowledge, ground-breaking drug discoveries are at the forefront of the medical sciences and society. For many diseases, however, the foundation of curing lies not exclusively in the availability of these sophisticated drugs, but rather in an accurate and early diagnosis. For colon cancer, for example, the survival rate of patients diagnosed at the early stage is 90%, whereas the survival rate of patients diagnosed in the critical stage is a mere 13% [1]. Similar figures hold for many more diseases.

Without diving too much in the details, one can see that a simple Google search already yields many reports underlining the importance of an early detection of disease for Alzheimer’s disease and Multiple Sclerosis.

Making an early biomedical diagnosis is thus often of vital importance.

Such diagnoses can be made in multiple ways. Often, they are made using analytical instruments, such as MRI scanners, NMR and mass spectrometry. These instrumentation methods can provide rich information on both the structure as well as the concentration of disease markers [2]. Even though these instruments can come to a sound diagnosis, they have a profound disadvantage: samples often need to be pre-treated and diagnoses cannot be made on-site, leading to prolonged processing times.

Due to this disadvantage, biosensors have found their way into society. In contrast to analytical instruments, biosensors can quickly diagnose a disease, can be used on-site and are often easy to use. iGEM TU Eindhoven has devised to develop a universal platform for biosensors. The designed platform is constructed from three major elements, being the recognition element which is used to detect disease markers, the signaling components which translate the detection into a measurable signal and a scaffold which joins the signaling components and recognition elements. An overview of the elements is presented below.

The Recognition Element – Aptamers

Since the discovery of the nucleic acid structure, nucleic acids were long thought to have a single function – storage of the heredity information as genetic instructions. Our perception on the function of DNA and RNA changed radically, however, as it was discovered that small RNA molecules could fold into a three-dimensional structure, exposing a surface onto which other small molecules could perfectly fit. Soon after the discovery that nucleic acids could have interaction with other molecules, Craig Tuerk and Larry Gold described a procedure, called SELEX, to isolate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands for proteins through a Darwinian-like evolution process carried out in vitro [3]

.

. SELEX is an acronym for Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment. The process is carried out in vitro and requires a very large oligonucleotide library (~1015 members), which can be generated by combinatorial DNA Synthesis. SELEX starts with incubation of the library with the target molecule. This incubation is followed by a washing step which ensures that only oligonucleotides with higher affinities are selected. Next, the oligonucleotides which are still present in the mixture after the washing step are recovered and amplified. During this amplification step, mutations are introduced into the oligonucleotides, yielding a new library. This library may again be incubated with the target molecule. Typically, these steps are repeated 8-15 times. In the last round of SELEX the oligonucleotides still present in the mixture are identified by sequencing.

SELEX is an acronym for Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment. The process is carried out in vitro and requires a very large oligonucleotide library (~1015 members), which can be generated by combinatorial DNA Synthesis. SELEX starts with incubation of the library with the target molecule. This incubation is followed by a washing step which ensures that only oligonucleotides with higher affinities are selected. Next, the oligonucleotides which are still present in the mixture after the washing step are recovered and amplified. During this amplification step, mutations are introduced into the oligonucleotides, yielding a new library. This library may again be incubated with the target molecule. Typically, these steps are repeated 8-15 times. In the last round of SELEX the oligonucleotides still present in the mixture are identified by sequencing.

The Rise of Aptamers

25 Years after the discovery of Tuerk’s and Gold’s invention of Systemic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential enrichment (SELEX), aptamers have become available for hundreds of ligands, including proteins, viruses, other small molecules and even whole cells

.

.

Aptamer sequences have been published for over 500 ligands. These ligands include small molecules, viruses, proteins and whole cells. Among these are some very notable ligands, such as HIV, cancerous cells and ricin, the extremely toxic compound which plays a prominent role in the critically acclaimed Breaking Bad series. These figures were obtained through Aptamer Base, a collaboratively created knowledge base about aptamers and the experiments that produced them, curated and maintained by a team of aptamer researchers. For more information, visit Aptamer Base's website

A major limitation of aptamers in comparison with antibodies is their stability in vivo, where nucleic acids are rapidly degraded. Aptamers which have been used as therapeutic agents, for example, suffered from a half-life of 2 minutes [9] . This problem has, however, partially been overcome by using chemical modifications to the aptamers. An example of these modifications are Spiegelmers [8] . These oligonucleotides’ backbones contain L-Ribose instead of R-Ribose – “spiegel” means mirror. These mirrored aptamers are more stable in vivo, because they suffer less from degradation.

Aptamers in Biotechnology

Since aptamers can be easily modified chemically, they can be attached to numerous surfaces, enabling their way into a wide array of biosensors and drug delivery systems. Generally, the biosensors couple binding of the aptamer to a change in structure in the latter, which generates either a fluorescent or electrical signal. Aptamers have also found their way into drug delivery systems. A particular example of such a system is developed by Wu et al., featuring aptamers targeted at cancer cells with lipid tails. These aptamers could be used as building blocks of micelles, enabling efficient delivery of the micelles to cancerous cells [10] .

Aptamers in our Biosensor

Aptamers constitute the ideal sensor domain for our universal membrane sensor: they can be targeted at virtually any molecule, can easily be attached to the membrane using SPAAC chemistry and offer affinities similar to antibodies. Taking into account their remarkable stability and small size, they are unmatched by the traditional recognition elements of biotechnology, antibodies. An essential requirement for our system which limits the choice of aptamers is bifunctionality: the system relies on bringing two membrane proteins in close proximity by binding the ligand with two different moieties. Conceptually, this bifunctionality can be reached either through the use of dual aptamers or through the use of split aptamers.

Figure 2: Bifunctionality is required to bring the membrane proteins into close proximity.

Dual Aptamers

The first way in which bifunctionality can be reached is through the use of dual aptamers acting on different binding sites, called apitopes. A well-known example of a ligand for which dual aptamers are available is human thrombin. A drawback of the use of dual aptamers is that these are in general not available for small molecules and viruses, significantly reducing the available targets for the aptamers. The main target for dual aptamers are proteins.

Split Aptamers

Alternatively, aptamers can be split into two parts. These parts can form heterodimers and thereby self-assemble into the three-dimensional structure required for binding the apitope. A crucial choice in engineering split aptamers is the choice of splitting site [11] . This choice is often not straightforward and the aptamer often suffers from a significantly decreased affinity. Obtaining split aptamers is, however, still in its infancy: of the approximately 100 small-molecule-binding aptamers, only six have been successfully engineered into split aptamers [11].

The Scaffold - OmpX

To realize conduction of a signal over the cell membrane, the aptamers have to be attached to a membrane protein. A procedure to attach oligonucleotides to membrane proteins has succesfully been tested by iGEM TU Eindhoven 2014. They presented this procedure as a part of their Click Coli project to the iGEM community. The procedure exploits the SPAAC reaction, which is one of the most well-described click chemistry reactions available (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Strain-promoted Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (SPAAC) is a well known click-chemistry reaction.

The reaction features two molecules, one functionalized with an azide group (A) and one functionalized

with a cyclooctyne group (B). SPAAC is very efficient and selective, no further reagents have to

be added to the reaction method and the reaction is completely bio-orthogonal. This image was adapted

from last year’s iGEM team’s wiki.

CPX & OmpX

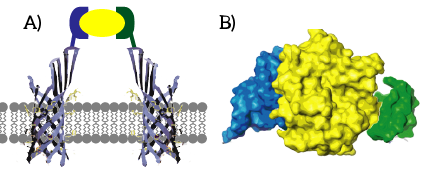

CPX is a membrane display protein developed by Rice et al. as an alternative to traditional display methodologies, such as yeast display and phage display [12]. The protein itself is derived from the naturally occuring Outer membrane protein X (OmpX) through circular permutation (see Figure 6). Circular permutation was a necessary step to obtain the termini on the exterior of the bacterial cells.

Figure 6: CPX (right) is a membrane protein derived from OmpX (left) through circular permutation.

OmpX and CPX feature signal sequences (yellow) which ensure that the membrane protein is localized

to E.coli’s outer membrane. These signal sequences are cleaved from the peptides after localization. In

CPX, an Amber stop codon was introduced to introduce a non-natural azide-functionalized amino acid.

Figure 7: The azide-functionalized amino acid enables clicking any DBCO-functionalized molecule to be attached to the cell membrane through SPAAC-click chemistry. iGEM TU Eindhoven 2014 called this azide-functionalized CPX COMPx.

Figure 8: For our signaling proteins, we revert to the basis: OmpX. We functionalize OmpX by introducing the Amber stop codon into its loops (red). The signaling domains are fused to OmpX C-terminally, since the N-terminus is occupied by the signaling sequence (yellow). The signaling sequence is cleaved from OmpX after localization.

The Loops

The Amber stop codon will be incorporated in the protruding loops of OmpX. We have chosen to introduce the mutations into the loops since they are easily accesible and are not a part of the beta-barrel of OmpX [2]. Hence, we believe that mutations in the loops will not disturb the secondary structure of OmpX (see Figure 9B).

Figure 9: A) The OmpX protein structure has been elucidated through NMR and X-ray crystallography, B) the square residues are important for the secondary structure of OmpX. To keep the structure intact, we introduce an amber stop codon in one of the protruding loops. Figure 5B is adapted from [13].

The to be substituted residues in the loops were chosen in such a way that the clicked aptamer would protrude from OmpX. Moreover, residues were selected such that the signaling proteins structure closely resembles OmpX natural’s structure. The serine residue in loop 2 was chosen since it was the only available residue with side-groups pointing outward from OmpX. The tyrosine residue in loop 3 was chosen both because tyrosine closely resembles the non-natural azide-functionalized amino acid (see Figure 10) and because the tyrosine points outward from OmpX.

Figure 10: The non-natural azide-functionalized amino acid closely resembles tyrosine

The Signaling Components - NanoLuc & Neongreen

Quite paradoxically, the number of signaling proteins pales in comparison with the vast amount of cellular responses. This signaling paradox can be explained by the fact that cells employ amazingly complex signaling pathways, which feature signal amplification, signal integration and cross communication [14]. In addition to the vast amount of effects signaling pathways can have, these pathways operate over a staggering range of time scales: some signaling pathways act within less than a second, whereas others affect cell behavior only after hours or days.

An essential aspect of a universal membrane sensor is that it allows for these wide ranges of time scales and responses. We believe that the modularity of our membrane sensor and the complexity of intracellular cell signaling allows for a wide range of responses. To enable the sensors to act upon a wide range of time scales we consider multiple intracellular signaling components. These components all respond to a decrease in mutual distance of the membrane proteins as a result of ligand binding.

Fast Signaling Components - Exploiting Bioluminiscence

Two well-known principles to translate a close proximity into a measurable signal are Resonance Energy Transfer and the use of split luciferases. Even though these principles are very different, both response elements emit light, yielding a measurable signal. After ligand binding, these signaling components yield an virtually immediate response.

Figure 11 - Resonance energy transfer (A) and split luciferases (B) both translate close proximity into a measurable signal in the form of light.

Fast Signaling Components - Explointing Bioluminiscence

Resonance Energy Transfer is a physical process which can take place between fluorophores light emission when they are in close proximity (1-10nm) [15]. An electron which has been transferred to its ‘excited state’ falls back to its ‘ground state’. The energy which is released by the electron falling back to its ground state is normally released in the form of light. In the case of Resonance Energy Transfer, however, the energy of the electron falling back to its ground state is not released in the form of light, but coupled to a transition of an electron in the RET Acceptor to from its ground state to the excited state (see Figure 12).

Figure 12 - Simplified energy-level diagram of RET. Panel A): Normally, an excited electron falls back to its ground state under the emission of light (a radiative transition). Panel B): In the case of Resonance Electron Transfer, an excited electron in the donor falls back to its ground state. This transition is coupled to the excitation of an electron in the acceptor. This excited electron falls back normally under the emission of light.

The efficiency of Resonance Energy Transfer is known to be dependent on a few factors, most importantly the relative orientation of the chromophores as well as the mutual distance of the chromophores [15]. A decreased mutual distance between the donor and acceptor increases the efficiency very significantly. This feature of Resonance Energy Transfer is exploited in the design of our membrane sensor. As a result of the reduced distance between the RET-donor and RET-acceptor, Resonance Energy Transfer is thus more efficient. As a result, relatively more light will be emitted by the acceptor when the lgiand is bound. The resulting signal is thus, per definition ratiometric. As a result of ligand binding, intensity of the light emitted by the donor will decrease and intensity of the light emitted by the acceptor will increase (see Figure 13).

Figure 13 - Panel A): Efficient energy transfer is not possible since the donor and fluorophore are to remote. Panel B): Efficient energy transfer is possible due to the proximity of the donor and acceptor. As a result, light intensity of the donor decreases whereas light intensity of the acceptor increases.

Split Luciferases

Luciferases are naturally occuring proteins which convert a substrate to a product and light. Many organisms feature luciferases to produce light, such as the sea spansy, fireflies and shrimps. These luciferases have been isolated from these organisms and can be succesfully used in vitro to produce light. Some luciferases have also been succesfully split into two complementary parts. These complementary parts can self-assemble into the functional luciferase, restoring its functionality to emit light by converting the substrate. As such, these split luciferases have become a major tool to study protein-protein interactions: these interactions are coupled to a close proximity of the proteins, allowing the parts to assemble into the functional luciferase and emit light (see Figure 14). We use these split luciferases in addition to BRET as a rapid signaling component.

Figure 14 - Panel A): The split parts of the luciferase are too remote to assemble into the functional luciferase, Panel B): Upon ligand binding, the two luciferases can self-assemble into the functional luciferase, restoring its capability to produce light from the substrate, yielding a measurable signal.

[1] American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2011-2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2011.

[2] W. Zhou, P.-J. J. Huang, J. Ding, and J. Liu, “Aptamer-based biosensors for biomedical diagnostics.,” Analyst, vol. 139, no. 11, pp. 2627–40, 2014.

[3] C. Tuerk and L. Gold, “Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase.,” Science, vol. 249, no. 4968, pp. 505–10, Aug. 1990.

[4] D. Musumeci and D. Montesarchio, “Polyvalent nucleic acid aptamers and modulation of their activity: A focus on the thrombin binding aptamer,” Pharmacol. Ther., vol. 136, no. 2, pp. 202–215, 2012.

[5] A. Cibiel, C. Pestourie, and F. Ducongé, “In vivo uses of aptamers selected against cell surface biomarkers for therapy and molecular imaging,” Biochimie, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 1595–1606, 2012.

[6] L. H. Lauridsen and R. N. Veedu, “Nucleic acid aptamers against biotoxins: a new paradigm toward the treatment and diagnostic approach.,” Nucleic Acid Ther., vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 371–9, 2012.

[7] A. Rhouati, C. Yang, A. Hayat, and J. L. Marty, “Aptamers: A promosing tool for ochratoxin a detection in food analysis,” Toxins (Basel)., vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 1988–2008, 2013.

[8] F. Radom, P. M. Jurek, M. P. Mazurek, J. Otlewski, and F. Jeleń, “Aptamers: Molecules of great potential,” Biotechnol. Adv., vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 1260–1274, 2013.

[9] B. J. Hicke, A. W. Stephens, T. Gould, Y.-F. Chang, C. K. Lynott, J. Heil, S. Borkowski, C.-S. Hilger, G. Cook, S. Warren, and P. G. Schmidt, “Tumor Targeting by an Aptamer,” J. Nucl. Med., vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 668–678, Apr. 2006.

[10] Y. Wu, K. Sefah, H. Liu, R. Wang, and W. Tan, “DNA aptamer-micelle as an efficient detection/delivery vehicle toward cancer cells.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 107, no. 1, pp. 5–10, 2010.

[11] A. D. Kent, N. G. Spiropulos, and J. M. Heemstra, “General approach for engineering small-molecule-binding DNA split aptamers,” Anal. Chem., vol. 85, no. 20, pp. 9916–9923, 2013.

[12] J. J. Rice, A. Schohn, P. H. Bessette, K. T. Boulware, and P. S. Daugherty, “Bacterial display using circularly permuted outer membrane protein OmpX yields high affinity peptide ligands.,” Protein Sci., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 825–36, Apr. 2006.

[13] J. Vogt and G. E. Schulz, “The structure of the outer membrane protein OmpX from Escherichia coli reveals possible mechanisms of virulence.,” Structure, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 1301–9, Oct. 1999.

[14] W. Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts, Molecular Biology of The Cell. Pearson, 2005.

[15] I. Medintz and N. Hildebrandt, Eds., FRET - Förster Resonance Energy Transfer. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2013.

[2] W. Zhou, P.-J. J. Huang, J. Ding, and J. Liu, “Aptamer-based biosensors for biomedical diagnostics.,” Analyst, vol. 139, no. 11, pp. 2627–40, 2014.

[3] C. Tuerk and L. Gold, “Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase.,” Science, vol. 249, no. 4968, pp. 505–10, Aug. 1990.

[4] D. Musumeci and D. Montesarchio, “Polyvalent nucleic acid aptamers and modulation of their activity: A focus on the thrombin binding aptamer,” Pharmacol. Ther., vol. 136, no. 2, pp. 202–215, 2012.

[5] A. Cibiel, C. Pestourie, and F. Ducongé, “In vivo uses of aptamers selected against cell surface biomarkers for therapy and molecular imaging,” Biochimie, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 1595–1606, 2012.

[6] L. H. Lauridsen and R. N. Veedu, “Nucleic acid aptamers against biotoxins: a new paradigm toward the treatment and diagnostic approach.,” Nucleic Acid Ther., vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 371–9, 2012.

[7] A. Rhouati, C. Yang, A. Hayat, and J. L. Marty, “Aptamers: A promosing tool for ochratoxin a detection in food analysis,” Toxins (Basel)., vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 1988–2008, 2013.

[8] F. Radom, P. M. Jurek, M. P. Mazurek, J. Otlewski, and F. Jeleń, “Aptamers: Molecules of great potential,” Biotechnol. Adv., vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 1260–1274, 2013.

[9] B. J. Hicke, A. W. Stephens, T. Gould, Y.-F. Chang, C. K. Lynott, J. Heil, S. Borkowski, C.-S. Hilger, G. Cook, S. Warren, and P. G. Schmidt, “Tumor Targeting by an Aptamer,” J. Nucl. Med., vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 668–678, Apr. 2006.

[10] Y. Wu, K. Sefah, H. Liu, R. Wang, and W. Tan, “DNA aptamer-micelle as an efficient detection/delivery vehicle toward cancer cells.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 107, no. 1, pp. 5–10, 2010.

[11] A. D. Kent, N. G. Spiropulos, and J. M. Heemstra, “General approach for engineering small-molecule-binding DNA split aptamers,” Anal. Chem., vol. 85, no. 20, pp. 9916–9923, 2013.

[12] J. J. Rice, A. Schohn, P. H. Bessette, K. T. Boulware, and P. S. Daugherty, “Bacterial display using circularly permuted outer membrane protein OmpX yields high affinity peptide ligands.,” Protein Sci., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 825–36, Apr. 2006.

[13] J. Vogt and G. E. Schulz, “The structure of the outer membrane protein OmpX from Escherichia coli reveals possible mechanisms of virulence.,” Structure, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 1301–9, Oct. 1999.

[14] W. Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts, Molecular Biology of The Cell. Pearson, 2005.

[15] I. Medintz and N. Hildebrandt, Eds., FRET - Förster Resonance Energy Transfer. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2013.