Difference between revisions of "Team:SF Bay Area DIYBio/Description"

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

Sunscreens are chemical compounds that absorb or reflect UV light, preventing it from damaging cells. We put sunscreen on our skin to protect the underlying skin cells from the damaging UV in sunlight. The Sun Protection Factor (SPF) rating of sunscreen essentially measure how much longer it allows someone to stay in the sun before getting a sunburn caused by UV-B light (290-320 nanometers). This is an imperfect measure of skin damage because invisible damage and skin aging are also caused by ultraviolet type A (UV-A, wavelengths 320–400 nm), increasing the risk of malignant melanomas. | Sunscreens are chemical compounds that absorb or reflect UV light, preventing it from damaging cells. We put sunscreen on our skin to protect the underlying skin cells from the damaging UV in sunlight. The Sun Protection Factor (SPF) rating of sunscreen essentially measure how much longer it allows someone to stay in the sun before getting a sunburn caused by UV-B light (290-320 nanometers). This is an imperfect measure of skin damage because invisible damage and skin aging are also caused by ultraviolet type A (UV-A, wavelengths 320–400 nm), increasing the risk of malignant melanomas. | ||

| − | UV rays carry high energy and are suspected of causing cancer through damage to the skin's DNA. High energy in sunlight comes in two forms: | + | UV rays carry high energy and are suspected of causing cancer through damage to the skin's DNA. High energy in sunlight comes in two forms: |

- UV-A (320-400 nanometers) | - UV-A (320-400 nanometers) | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

- Repeat! | - Repeat! | ||

| − | In principle, we can rely on the UV exposure to introduce mutations, and select for the phenotype we want to optimize. In practice, we use error-prone Rolling Circle Amplification to introduce mutations just in the engineered plasmid carrying the shinorine biosynthesis genes | + | In principle, we can rely on the UV exposure to introduce mutations, and select for the phenotype we want to optimize. In practice, we use error-prone Rolling Circle Amplification to introduce mutations just in the engineered plasmid carrying the shinorine biosynthesis genes. |

| − | [[File:RCA Animation.gif|400px]] | + | [[File:RCA Animation.gif|400px|right]] |

| + | In Rolling Circle Amplification, a phage polymerase is used to copy a circular piece of DNA. The polymerase is so processive that it will displace the previously copied strand when it circles around the plasmid, resulting in linear strand containing many copies of the plasmid. By changing some of the salts present in the reaction, we can cause the polymerase to become far more error-prone, incorporating single-base errors at random locations. | ||

| − | + | Error-prone Rolling Circle Amplification is a highly effective and convenient alternative to doing error-prone PCR to amplify a stretch of DNA while introducing mutations. One of its main benefits is that the reaction happens at a single temperature, so no temperature cycling is needed! | |

| − | This could in theory lead to a greatly simplified protocol: | + | If we go directly from transformation to growing in liquid medium, and then do the selection in liquid medium, we may never actually need to grow isolates during each round of Directed Evolution. This could in theory lead to a greatly simplified protocol: |

[[File:Directed Evolution Animation.gif|600px]] | [[File:Directed Evolution Animation.gif|600px]] | ||

Latest revision as of 03:00, 22 November 2015

Bio Sun Block (Evolved Bacterial Sunscreen)

Introduction

No, not sunscreen for bacteria - sunscreen made by bacteria. We are going to make e.coli bacteria create shinorine, a UV absorbing compound that is currently being extracted from algae as an eco-friendly sunscreen.

Genetic Engineering is arguably the greatest leap forward in human understanding and manipulation of nature in the whole history of mankind, above and greater than the invention of fire and the wheel combined. This project makes use of Genetic Engineering to force a bacteria to create a compound that it would never make and then use the tools of evolution to enhance that ability.

E.coli can easily be killed by UV light. By equipping it with the genes to produce UV absorbing compounds, we expect that the E. coli will become somewhat UV resistant as well. After designing the process, we want to make it better, so we will employ “directed evolution” to make the process better. We think that if we stress the bacteria with UV that they will start to evolve better and more efficient mechanisms to protect themselves from UV.

So that is our project: start some bacteria making sunscreen then subject them to a lot of sunshine and they will evolve to make more and better sunscreen.

Physics of sunscreen

Sunscreens are chemical compounds that absorb or reflect UV light, preventing it from damaging cells. We put sunscreen on our skin to protect the underlying skin cells from the damaging UV in sunlight. The Sun Protection Factor (SPF) rating of sunscreen essentially measure how much longer it allows someone to stay in the sun before getting a sunburn caused by UV-B light (290-320 nanometers). This is an imperfect measure of skin damage because invisible damage and skin aging are also caused by ultraviolet type A (UV-A, wavelengths 320–400 nm), increasing the risk of malignant melanomas.

UV rays carry high energy and are suspected of causing cancer through damage to the skin's DNA. High energy in sunlight comes in two forms:

- UV-A (320-400 nanometers)

- UV-B (290-320 nanometers)

The UVB waves tend to receive more criticism than the less energetic UVA waves. But, in actual fact, both UVB and UVA can damage the skin. Unfortunately, the chemistry of sunscreen, in most cases, does not enable the blocking of UVA as effectively, if at all, as they do UVB.

Note that the germicidal UV lights we use in the laboratory (e.g. built into the biosafety cabinet) emit the even short wavelength and even higher energy UV-C light (wavelengths 100–280nm). These wavelengths do not actually occur in natural sunlight, because they are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere.

Mycosporine-like amino acids

Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) are small secondary metabolites produced by organisms that live in environments with high volumes of sunlight, usually marine environments. The structures of over 30 Mycosporine-like amino acids have been resolved and all contain a central cyclohexenone or cyclohexenimine ring and a wide variety of substitutions. The ring structure is thought to absorb UV light and accommodate free radicals. All MAAs absorb ultraviolet light, typically between 310 and 340 nm. It is this light absorbing property that allows MAAs to protect cells from harmful UV radiation. They are commonly described as “microbial sunscreen” but their function is not limited to sun protection.

Though most MAA research is done on their photo-protective capabilities, they are also multifunctional secondary metabolites that have many cellular functions. MAAs are effective antioxidant molecules and are able to stabilize free radicals within their ring structure. In addition to protecting cells from mutation via UV radiation and free radicals, MAAs are able to boost cellular tolerance to desiccation, salt stress, and heat stress.

Anabaena variabilis shinorine gene cluster

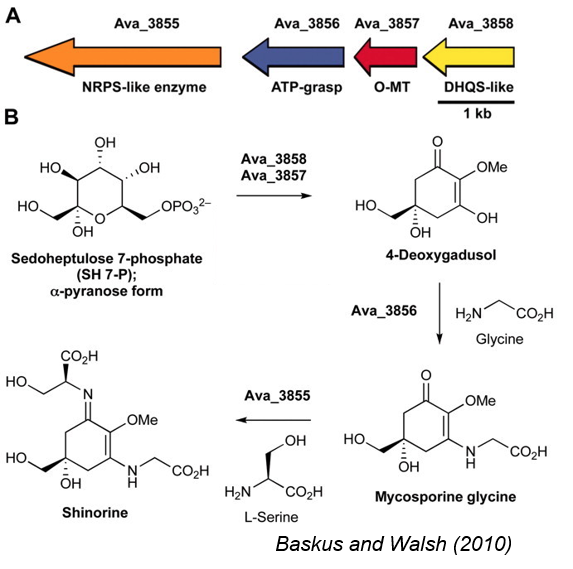

Baskus and Walsh (2010) identified a gene cluster in A. variabilis that produced shinorine, a well-studied MAA.

The U. Minnesota 2012 iGEM team successfully transformed the entire gene cluster, but did not observe the production of shinorine, the final metabolite in the pathway - suggesting that the final enzyme of the pathway was not active. Unfortunately, they did not submit any parts to the iGEM Registry.

Alternative Mycosporine enzymes

The Minnesota 2012 team was not able to get the final step in the pathway, so we also searched for alternative enzymes in other cyanobacteria

Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133: final enzyme produces shinorine and porphyra-334

We identified 7 other homologous genes from known shinorine producing cyanobacteria

Directed Evolution

UV resistance is an ideal target for Directed evolution:

- Introduce mutations

- Select for UV resistance

- Repeat!

In principle, we can rely on the UV exposure to introduce mutations, and select for the phenotype we want to optimize. In practice, we use error-prone Rolling Circle Amplification to introduce mutations just in the engineered plasmid carrying the shinorine biosynthesis genes.

In Rolling Circle Amplification, a phage polymerase is used to copy a circular piece of DNA. The polymerase is so processive that it will displace the previously copied strand when it circles around the plasmid, resulting in linear strand containing many copies of the plasmid. By changing some of the salts present in the reaction, we can cause the polymerase to become far more error-prone, incorporating single-base errors at random locations.

Error-prone Rolling Circle Amplification is a highly effective and convenient alternative to doing error-prone PCR to amplify a stretch of DNA while introducing mutations. One of its main benefits is that the reaction happens at a single temperature, so no temperature cycling is needed!

If we go directly from transformation to growing in liquid medium, and then do the selection in liquid medium, we may never actually need to grow isolates during each round of Directed Evolution. This could in theory lead to a greatly simplified protocol:

UV Kill Curve experiments

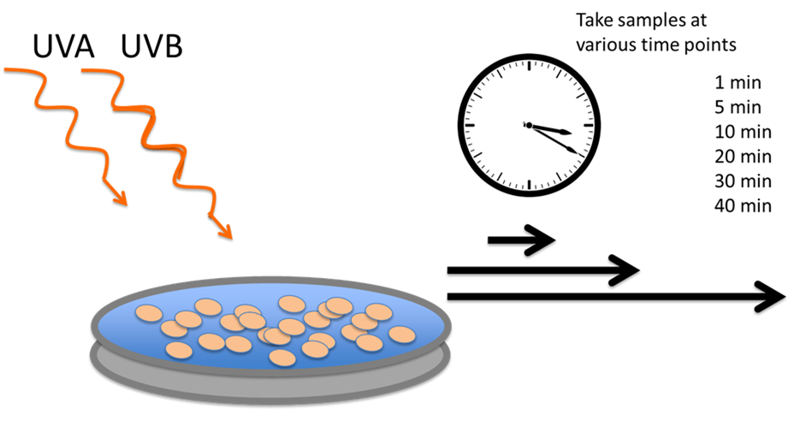

In order to do the Directed Evolution experiments, we first need to figure out how much UV light we expose our E. coli cells to. During the selection phase, we want to kill most, but not all cells, so as to impose a strong selective pressure for improved UV resistance.

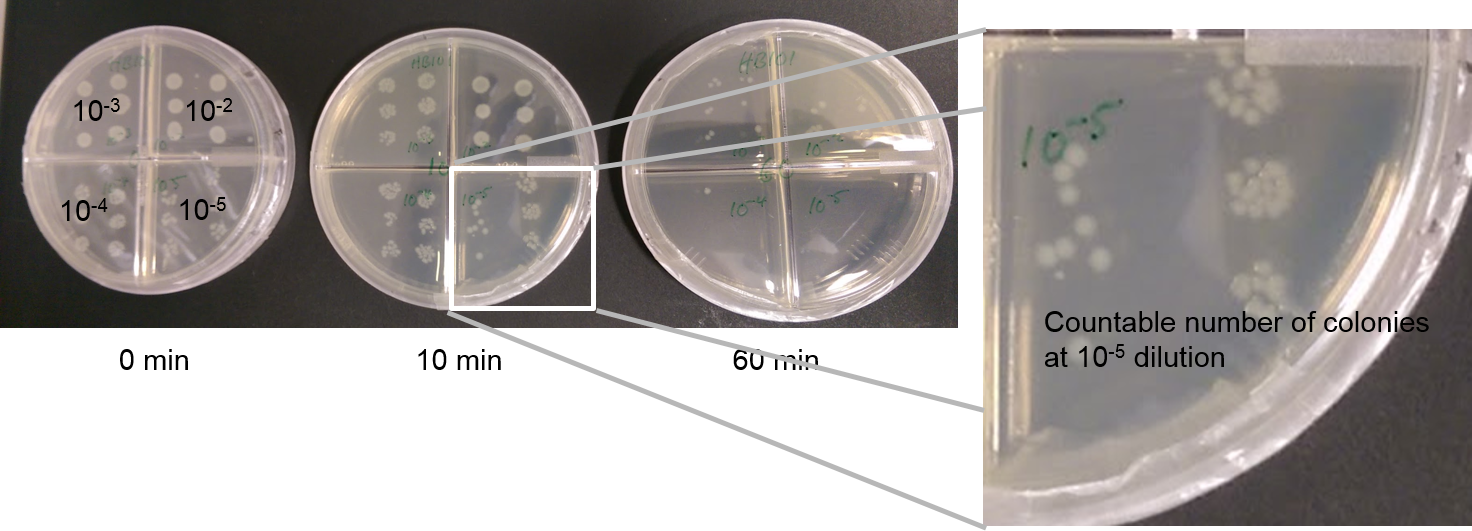

So we first generated a "Kill Curve" for our E. coli cells, counting how many cells are left alive after exposure to different doses of UV. We simple expose a liquid E. coli culture in a very shallow Petri dish to UV light in our home-made UV exposure box, and take out samples every couple of minutes.

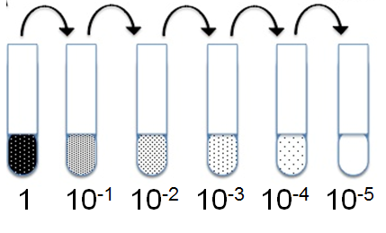

From these samples we then create a dilution series, diluting 1:10 down to a dilution of 1:10^-5^, and spot drops of these dilutions on agar plates.

Finaly, we count the colonies, at whichever dilution factor yields a countable number of colonies. Knowing the dilution factor, we can then work back to how many colony forming units were left in the liquid culture exposed to UV light.