Difference between revisions of "Team:KU Leuven/Research/Idea"

| Line 614: | Line 614: | ||

<p style="font-size:1.3em; text-align: center"> | <p style="font-size:1.3em; text-align: center"> | ||

Address: Celestijnenlaan 200G room 00.08 - 3001 Heverlee<br> | Address: Celestijnenlaan 200G room 00.08 - 3001 Heverlee<br> | ||

| − | Telephone | + | Telephone: +32(0)16 32 73 19<br> |

| − | + | Email: igem@chem.kuleuven.be<br> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 667: | Line 667: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div id="kolo"> | <div id="kolo"> | ||

| − | <a | + | <a><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/15/KUL_Ko-Lo_Instruments_logo_transparant.png" alt="Ko-Lo Instruments" width="95%"></a> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div id="regensys"> | <div id="regensys"> | ||

Revision as of 16:14, 15 September 2015

Idea

Introduction

Intrigued by the patterns occuring in nature, we started our research to design possible interaction schemes and genetic circuits. Looking at specialised literature, we were able to find some interesting papers concerning the formation of patterns using Escherichia coli (E. coli). For example, Basu et al. created ring-like patterns based on chemical gradients of an acyl-homoserine lactone (OHHL) signal that is synthesized by ‘sender’ cells. In ‘receiver’ cells, designed genetic networks respond to differences in OHHL concentrations [1]. Liu et al. created periodic stripes of high and low cell densities of E. coli, by inhibiting cell motility when cell density was high [2]. Combining our innovative and altered chemotaxis intercellular relationship with basic principles from both papers, allowed us to design our own circuit which will be elucidated in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1

Signaling cascade for motility in E.coli

Our design

Two different cell types, called A and B, interact and create patterns. In order to achieve the desired behavior, the cells used in our experiments are derived from Escherichia coli K12 and have specific knockouts. Cell type A has a deletion of tar and tsr , whereas in cell type B both tar and cheZ are knocked out. Tar and Tsr are two major chemotactic receptors, guiding the cells towards nutrients. When a certain small molecule binds one of these receptors, a signaling cascade is initiated. In our specific case, cell’s A deletion of both tsr and tar causes them to be insensitive to leucine (as a repellent and attractant). Cell B on the other hand, who lost only Tar, is repelled by leucine. [3] Upon recognition of the small molecule (in this case leucine), the receptor transduces the signal through a set of Che proteins. This group of methylesterases and phosphatases regulates the rotation of the flagella (Figure 1). In E. coli, the motors turn counterclockwise (CCW) in their default state, allowing several filaments on the cell to join together in a bundle and propel the cell smoothly forward. The interaction of phospho-CheY and a motorprotein causes the motors to switch to clockwise (CW) rotation, inducing dissociation of the filament bundle and tumbling of the cell. (Figure 1) [4] To regulate CheY activity, a protein called CheZ removes a phosphate group and subsequently inhibits its activity. Cells lacking this protein are not able to swim and will tumble excessively and incessantly [5].

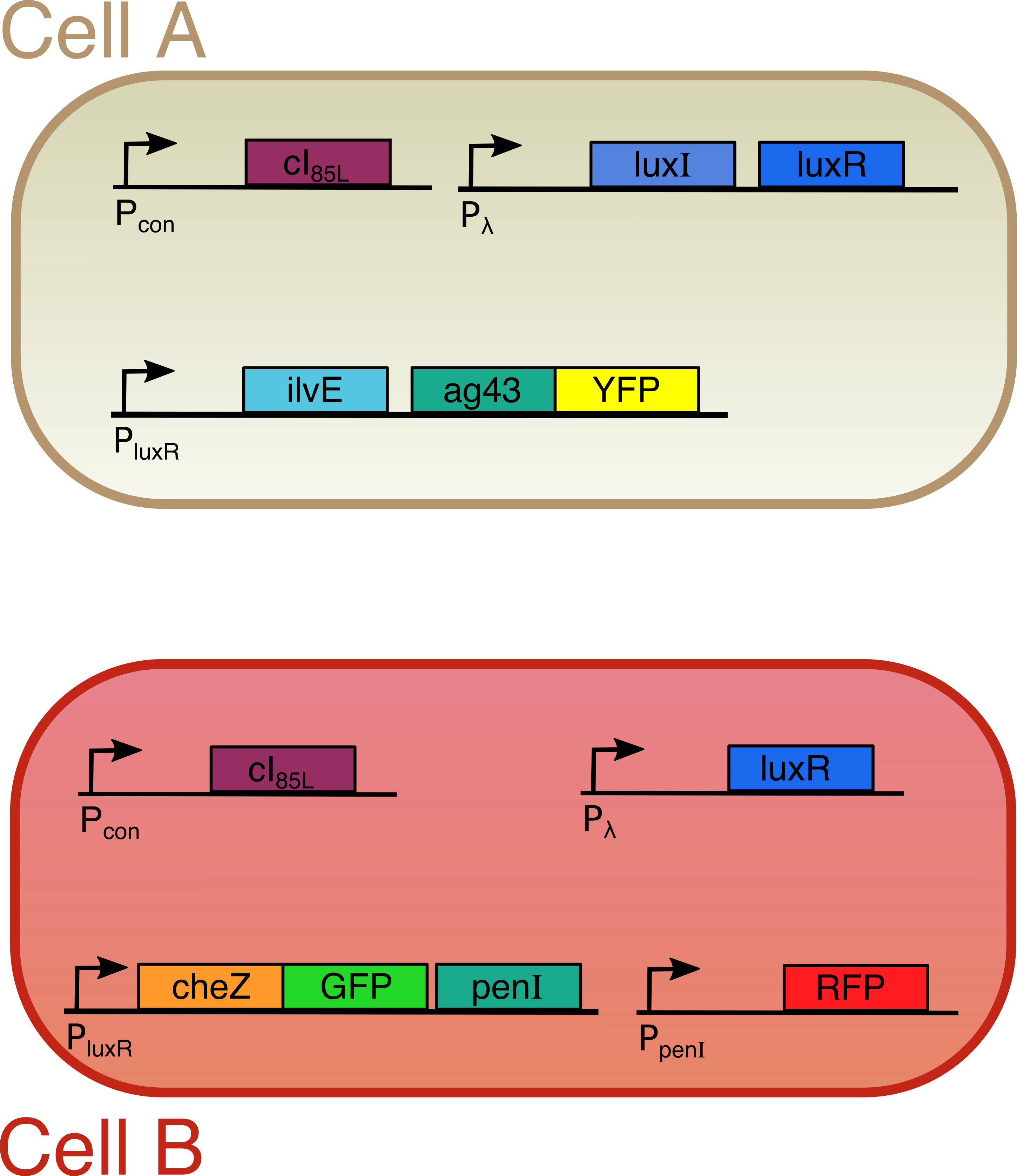

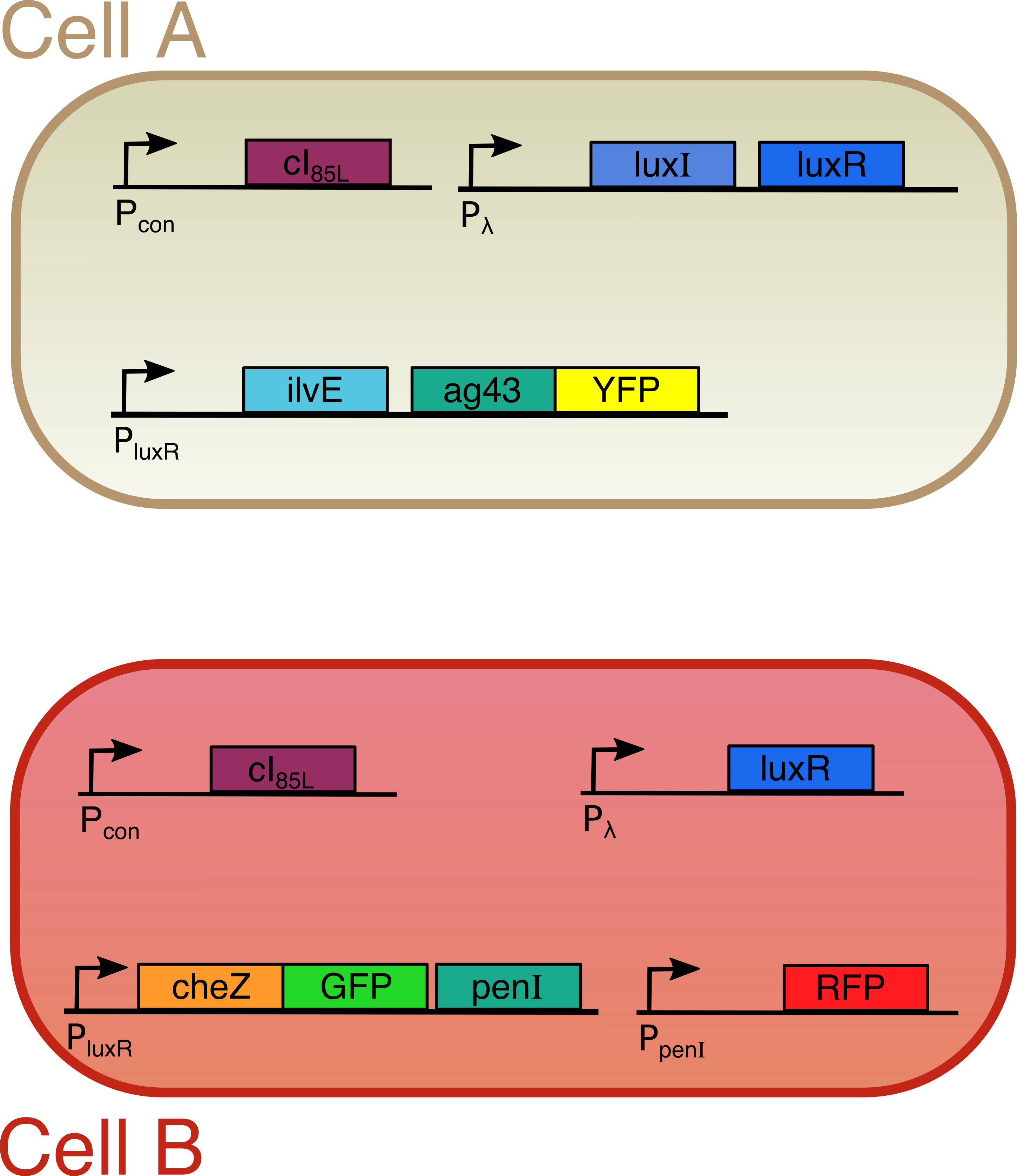

Both cells are transfected with only one plasmid each (Figure 2). Both plasmids contain a temperature sensitive cI repressor protein, which is constitutively expressed. This repressor is only able to bind to the lambda promoter at temperatures below a certain threshold (between 30°C and 42°C). At elevated temperatures, cI is unable to bind to the promoter region enabling RNA polymerase to start transcription. [6] From the lambda promoter in cell A, two essential protagonists for our system are expressed: the OHHL-producing enzyme LuxI and the transcription activator LuxR [7]. On the contrary, cell B only contains the lambda promoter coupled to the luxR gene. In cell A, we coupled the expression of an autoaggregation factor Ag43-YFP and a leucine-producing enzyme Transaminase B to the OHHL-LuxR regulated promoter. Ag43 causes cells A to stick together and form clumps [8]. At the same time, Transaminase B catalyses the production of the repellent leucine [9]. The repellent has no impact on cell A, since it does not contain the necessary receptors anymore. Cell B on the other hand is repelled by leucine, and contains the Lux promoter coupled to CheZ-GFP and the transcription repressor PenI. This repressor binds to the Pen-promoter [10], which regulates the transcription of a red fluorescent protein (RFP). The use of fluorescent fusion proteins specific for a certain state (aggregated, swimming, tumbling) facilitates the read-out of our patterns. In order to measure the concentration of the key proteins LuxI and LuxR, they were fused with a His-tag and an E-tag respectively. To ensure rapid degradation of proteins whose expression is dependent on OHHL concentration, an LVA tag was fused to CheZ, GFP and RFP. (Figure 3)

Figure 3

The designed circuit

Hypotheses

We expect that by raising the temperature, cells of type A will start to secrete OHHL. This OHHL will activate cells A to produce Ag43 and leucine and cells B to express CheZ-GFP and PenI. Cells A will start to form distinct spots on the agar plate and will emit yellow light (λ = 528 nm). At the same time, cells B will be repelled from cells A by leucine, the expression of PenI will repress the expression of RFP and thus the red color, whereas the expression of CheZ will enable the bacteria to swim and render them green. When they have swum too far away from cells A, the concentration of OHHL decreases to levels which are too low for LuxR to bind to the promotor. When LuxR cannot bind anymore, CheZ and PenI will no longer be expressed causing the bacteria to tumble incessantly and become red again. Figure 4 shows the patterns we expect in the end

Figure 4

Expected patterns

Introduction

Scientists have been interested in pattern formation for a long time. Using different techniques, they were already able to generate nice and sometimes complex patterns on a petri dish (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Example of pattern formation on a petri dish (picture from Chenli Liu et al. )

The basic principles behind this formation rely on two fundamental properties of bacteria: the communication between different cells and their ability to swim. Our project combines both properties, and adds another dimension to it. In our system, we also included a mechanism that causes the first type of bacteria to clump together and at the same time chase away the second type. According to our first rough models, this should allow to generate nice patterns.

Our circuit

Our circuit consists of two different cells, custom-made for this project. We made the first one, called cell A, in this way that it is never repelled by itself or the other cell. The second one, called cell B, is unable to swim under normal circumstances and is sensitive to certain repelling molecules. Each of these cells produce different proteins. These cellular workforces execute a variety of functions:

Cell A contains two proteins (LuxI and LuxR). LuxI produces a small molecule called OHHL. Binding of OHHL together with LuxR to a specific DNA is needed to start up the synthesis of a second group of proteins (Transaminase B and Ag43). Ag43 is some sort of molecular velcro, causing cell A to aggregate. Transaminase B makes the molecules that scare away cell B.

Cell B on the other hand only contains LuxR instead of both LuxI and LuxR. Because of this lack of the OHHL producing enzyme LuxI, the proteins whose production is LuxR and OHHL dependent (in this case CheZ and PenI) are only expressed when cell B is close to cell A. In this case, expression of CheZ restores the ability to swim, whereas PenI stops the synthesis of a red fluorescent protein. This red color indicates the standard and non-induced situation for cell B, and is used as an easy read-out to distinguish the different cells.

Figure 2

The designed circuit

In order to visualize induced patterns nicely, we also gave some proteins (Ag43 and CheZ) a color by fusing two fluorescent proteins to them. The whole system is temperature sensitive, since the expression of LuxI and LuxR starts when temperatures are elevated to around 42°C. To achieve this we include a protein (cI) that binds to the DNA at a specific site and blocks production of LuxI and/or LuxR. However, at higher temperatures, this protein starts to loose its three dimensional structure and the blockade is lifted initiating the whole pattern formation process. Figure 2 gives a summary of our circuit

Expectations

So, in theory, when we raise the temperature, the pattern formation will start. Cell A will start to aggregate and will obtain a yellow color. At the same time, it will produce the repellents for cell B. In cell B, the red color will disappear, and the swimming motility will be restored. A green color will appear simultaneously. However, when cell B is too far from cell A, the second group of proteins is no longer expressed, leading to a subsequent loss of motility and green color, and the return of the red fluorescent color.

Normally, this will produce distinct yellow spots, with a green circle around of swimming cells B. At the edges, the immotile red cells B will start to appear. Figure 4 shows the patterns we expect in the end

Figure 4

References

| [1] | Subhayu Basu, Yoram Gerchman, Cynthia H. Collins, Frances H. Arnold & Ron Weiss “A synthetic multicellular system for programmed pattern formation” Nature 434 (2005): 1130-1134. |

| [2] | Chenli Liu, Xiongfei Fu, Lizhong Liu, Xiaojing Ren, Carlos K.L. Chau, Sihong Li, Lu Xiang, Hualing Zeng, Guanhua Chen, Lei-Han Tang, Peter Lenz, Xiaodong Cui, Wei Huang, Terence Hwa, Jian-Dong Huang” Sequential Establishment of Stripe Patterns in an Expanding Cell Population” Science 334 no. 6053 (2011) : 238-241. |

| [3] | Khan, S., and D. R. Trentham. “Biphasic Excitation by Leucine in Escherichia Coli Chemotaxis.” Journal of Bacteriology 186, no. 2 (2004): 588-592. |

| [4] | Sarkar MK, Paul K, Blair D , “Chemotaxis signaling protein CheY binds to the rotor protein FliN to control the direction of flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli.” PNAS 107, no. 20 (2010): 9370-9375. |

| [5] | Kuo, Scot C., and D. E. Koshland. “Roles of cheY and cheZ Gene Products in Controlling Flagellar Rotation in Bacterial Chemotaxis of Escherichia Coli.” Journal of Bacteriology 169, no. 3 (1987): 1307–14. |

| [6] | Villaverde, A., A. Benito, E. Viaplana, and R. Cubarsi. “Fine Regulation of cI857-Controlled Gene Expression in Continuous Culture of Recombinant Escherichia Coli by Temperature.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 59, no. 10 (1993): 3485–87. |

| [7] | Clay Fuqua , Matthew R. Parsek , and E. Peter Greenberg “Regulation of Gene Expression by Cell-to-Cell Communication: Acyl-Homoserine Lactone Quorum Sensing” , Annu. Rev. Genet. (2001) 35:439–68 |

| [8] | Ulett, G. C. “Antigen-43-Mediated Autoaggregation Impairs Motility in Escherichia Coli.” Microbiology 152, no. 7 (2006): 2101–2110. |

| [9] | James L. Cox, Betty J. Cox , Vincenzo Fidanza , David H. Calhoun “The complete nucleotide sequence of the iZvGMEDA cluster of Escherichia coli K-12” Gene 56, Issues 2–3 (1987): 185–198. |

| [10] | Wittman, V., H. C. Lin, and H. C. Wong. “Functional Domains of the Penicillinase Repressor of Bacillus Licheniformis.” Journal of Bacteriology 175, no. 22 (1993): 7383–7390. [10] |