Difference between revisions of "Team:Chalmers-Gothenburg/OtherApplications"

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

<h2>Gibson 2.0</h2> | <h2>Gibson 2.0</h2> | ||

| − | <p>The world of synthetic biology is growing tremendously fast and part of it is the development of new tools. In the year 2003, the BioBrick standard was introduced as an intelligent way of using restriction sites to construct genetic constructions, however the | + | <p>The world of synthetic biology is growing tremendously fast and part of it is the development of new tools. In the year 2003, the BioBrick standard was introduced as an intelligent way of using restriction sites to construct genetic constructions, however the method is limited due to the fact that the DNA sequence needs to contain those specific restriction sites in the end of the fragments, and it can’t have any of those restriction site inside the DNA fragment. </p> |

| − | <p>In 2009, a | + | <p>In 2009, a method was introduced which avoids potential problems associated with restriction sites and –enzymes, called Gibson assembly. The method utilizes sequence overlaps between the two DNA fragments to fuse them together. Unlike BioBrick assembly there are no requirements on the overlapping region which is one of the strengths of Gibson assembly </p> |

[[File:ChalmersgothenburgOtherApplications4.png|400px]] | [[File:ChalmersgothenburgOtherApplications4.png|400px]] | ||

<p class="figuretext">Figure 4, the mechanism of Gibson assembly. 1) An exonuclease chews of one of the two strands of the two DNA fragments (blue/green and orange/green). 2) The two fragments bind together due to their overlapping region (green). 3) A DNA polymerase fills in the gaps and a ligase repair the backbone nicks. 4) The DNA fragments are fused.</p> | <p class="figuretext">Figure 4, the mechanism of Gibson assembly. 1) An exonuclease chews of one of the two strands of the two DNA fragments (blue/green and orange/green). 2) The two fragments bind together due to their overlapping region (green). 3) A DNA polymerase fills in the gaps and a ligase repair the backbone nicks. 4) The DNA fragments are fused.</p> | ||

| − | |||

<p>Now we introduce a concept for next generation of DNA assembly, Gibson 2.0. The concept is very similar to the normal Gibson assembly and is also compatible with normal Gibson reactions at the same time, but it removes the need for a specific overlap all together. The method is inspired by our repair mechanism and uses the normal Gibson proteins, but also a Recombinase and an oligonucleotide. The reason why no sequence overlap is needed is the exploitation of the recombinase and oligonucleotide to create an overlap during the reaction. </p> | <p>Now we introduce a concept for next generation of DNA assembly, Gibson 2.0. The concept is very similar to the normal Gibson assembly and is also compatible with normal Gibson reactions at the same time, but it removes the need for a specific overlap all together. The method is inspired by our repair mechanism and uses the normal Gibson proteins, but also a Recombinase and an oligonucleotide. The reason why no sequence overlap is needed is the exploitation of the recombinase and oligonucleotide to create an overlap during the reaction. </p> | ||

| Line 40: | Line 39: | ||

<p>There is a wide range of laboratory markers available for use. Some of the most common markers confer resistance versus a specific chemical like antibiotic resistance. These markers are often very effective since the selective medium does not only kill the cells without the wanted DNA constructions, but it also kills potential contaminants. However, the use of antibiotics could potentially cause selective pressure for antibiotic resistance in pathogens if the antibiotics isn’t taken care of properly. If toxic chemicals are used, it could potential harm humans. Therefore extra safety measures need to be taken to combat these risks.</p> | <p>There is a wide range of laboratory markers available for use. Some of the most common markers confer resistance versus a specific chemical like antibiotic resistance. These markers are often very effective since the selective medium does not only kill the cells without the wanted DNA constructions, but it also kills potential contaminants. However, the use of antibiotics could potentially cause selective pressure for antibiotic resistance in pathogens if the antibiotics isn’t taken care of properly. If toxic chemicals are used, it could potential harm humans. Therefore extra safety measures need to be taken to combat these risks.</p> | ||

| − | <p>An alternative method is the use of auxotrophic markers, which is based on knocking out a protein in a pathway which synthesizes an essential biomolecule like a nucleotide or an amino acid. If the cells are grown on a complex nutrient medium, e.g. LB for E. coli or YPD for S. cerevisiae, the cells will survive. But if they are grown in a media without that specific biomolecule the only survivors will be the cells with the knocked out gene reinserted. The problem with auxotrophic markers could be mixing or contamination by another strain without that specific knockout. </p> | + | <p>An alternative method is the use of auxotrophic markers, which is based on knocking out a protein in a pathway which synthesizes an essential biomolecule like a nucleotide or an amino acid. If the cells are grown on a complex nutrient medium, e.g. LB for <i>E. coli</i> or YPD for <i>S. cerevisiae</i>, the cells will survive. But if they are grown in a media without that specific biomolecule the only survivors will be the cells with the knocked out gene reinserted. The problem with auxotrophic markers could be mixing or contamination by another strain without that specific knockout. </p> |

<p> Our concept for the next generation marker is based on our repair system. The used strain should have the needed parts for the repair system but one. During transformation/transfection the last repair protein should be added and then selection is done by irradiating the sample. The transformed cells would survive while the non-transformed cells would die. The same applies for eventual contaminants. So far it has the same effect as the chemical markers, but without the downsides of auxotrophic markers. However, since the irradiation causes no chemical waste handling it would be the more ethical choice.</p> | <p> Our concept for the next generation marker is based on our repair system. The used strain should have the needed parts for the repair system but one. During transformation/transfection the last repair protein should be added and then selection is done by irradiating the sample. The transformed cells would survive while the non-transformed cells would die. The same applies for eventual contaminants. So far it has the same effect as the chemical markers, but without the downsides of auxotrophic markers. However, since the irradiation causes no chemical waste handling it would be the more ethical choice.</p> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:31, 19 September 2015

CRISPR all in one

Most CRISPR-technology vectors with both gRNA and Cas9 expression have expression of both genes under control of different promoters. Due to CAS9s immense size there are often problems working with this technology and having two regulatory sequences does not help. This effect is especially detrimental while using complex eukaryotic regulatory sequences like the 1077 bP long promotor pCLN1, used in iGEM 2014 Team Gothenburg.

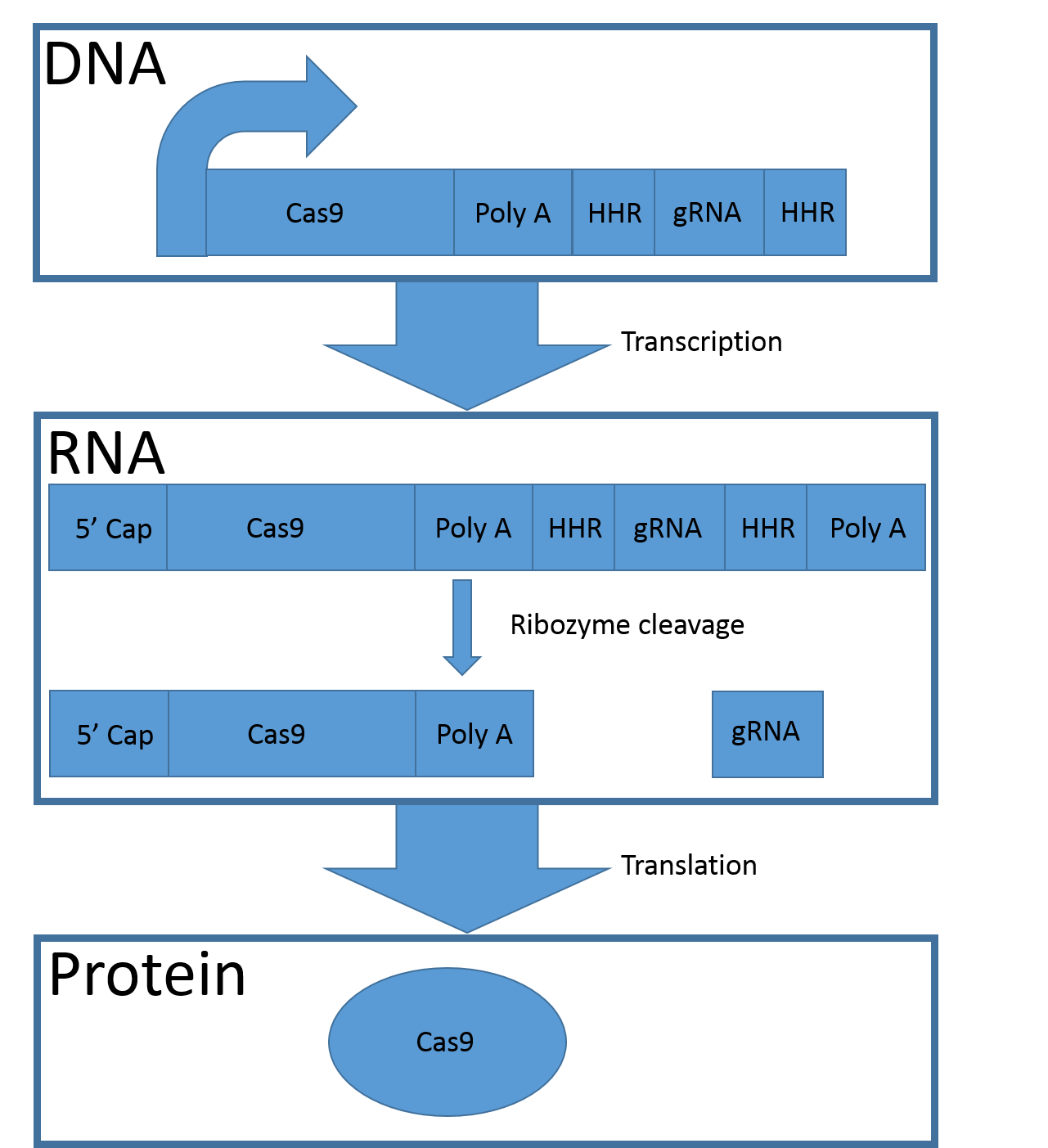

To minimize the need for regulatory sequences (promoters and terminators) we introduced a new system which has a similar effect as a bacterial operon. The system is capable of regulating one protein-encoding gene and one RNA-sequence in eukaryotes using only one promotor. We call it CGC1 (Cas9 gRNA complex one) and used it in the signal amplification mechanism in our detection system.

To obtain both of the complex components a set of requirements need to be fulfilled. First, the coding sequence for CAS9 should be flanked by the ‘5 cap and the poly A- tail to be transported outside the nuclear envelope and be translated into the protein. Second, the gRNA must be free from polyA tail and 5’ cap to avoid relocation into the cytoplasm and degradation

The solution to the problem uses two simple parts, hammerhead ribozymes and synthetic poly-A tails. The hammerhead ribozymes are functional secondary RNA structures which induce self-cleavage. The use of ribozymes to create gRNA are quite common in the research community but also in iGEM, an example of a team using ribozymes to produce gRNA in vivo are iGEM 2014 Team Gothenburg. The other CGC1 part, the synthetic poly A tail, is used as the new poly-A tail after ribozyme cleavage ensuring the cas9 mRNA translocation and translation.

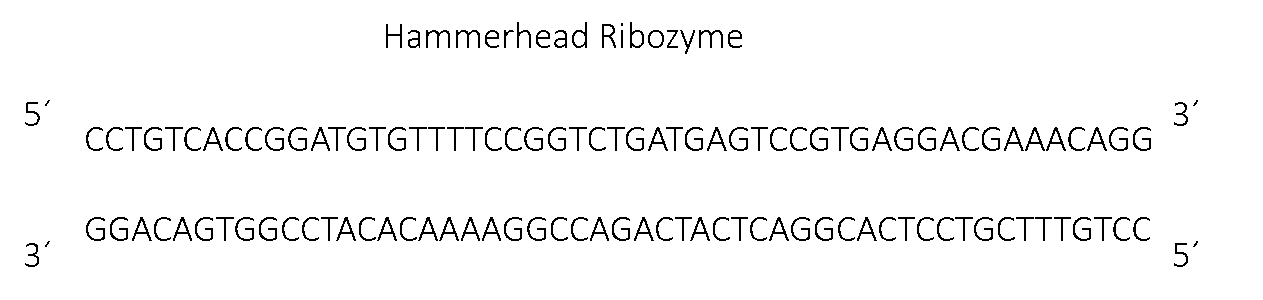

Figure 1, the sequence for the hammer head ribozyme.

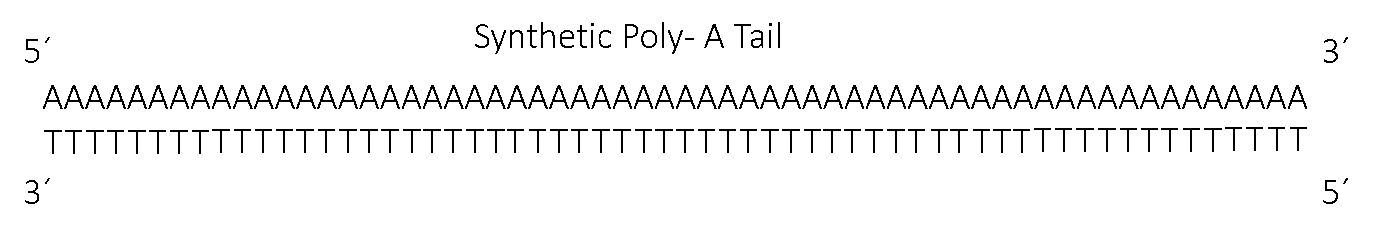

Figure 2, the Sequence of the Synthetic Poly-A tail

To use the two parts in the system, the protein-encoding sequence should be put immediately downstream of the promotor and RBS. The protein-encoding sequence should be followed by the synthetic poly-A tail and then a hammerhead ribozyme. After the ribozyme the wanted non-coding RNA sequence (here: the gRNA-encoding sequence) should be placed and last another ribozyme.

Figure 3, Mechanism of the CGC1 system. The CGC1 gene is transcribed and the natural 5’ cap and the poly-A tail are added to the sequence. The two hammerhead ribozymes (HHR) induce their own cleavage, which separates the protein coding sequence from the gRNA. The natural 5´cap and the synthetic poly-A tail (Poly A) ensure the translation of the protein coding sequence (Cas9).

Gibson 2.0

The world of synthetic biology is growing tremendously fast and part of it is the development of new tools. In the year 2003, the BioBrick standard was introduced as an intelligent way of using restriction sites to construct genetic constructions, however the method is limited due to the fact that the DNA sequence needs to contain those specific restriction sites in the end of the fragments, and it can’t have any of those restriction site inside the DNA fragment.

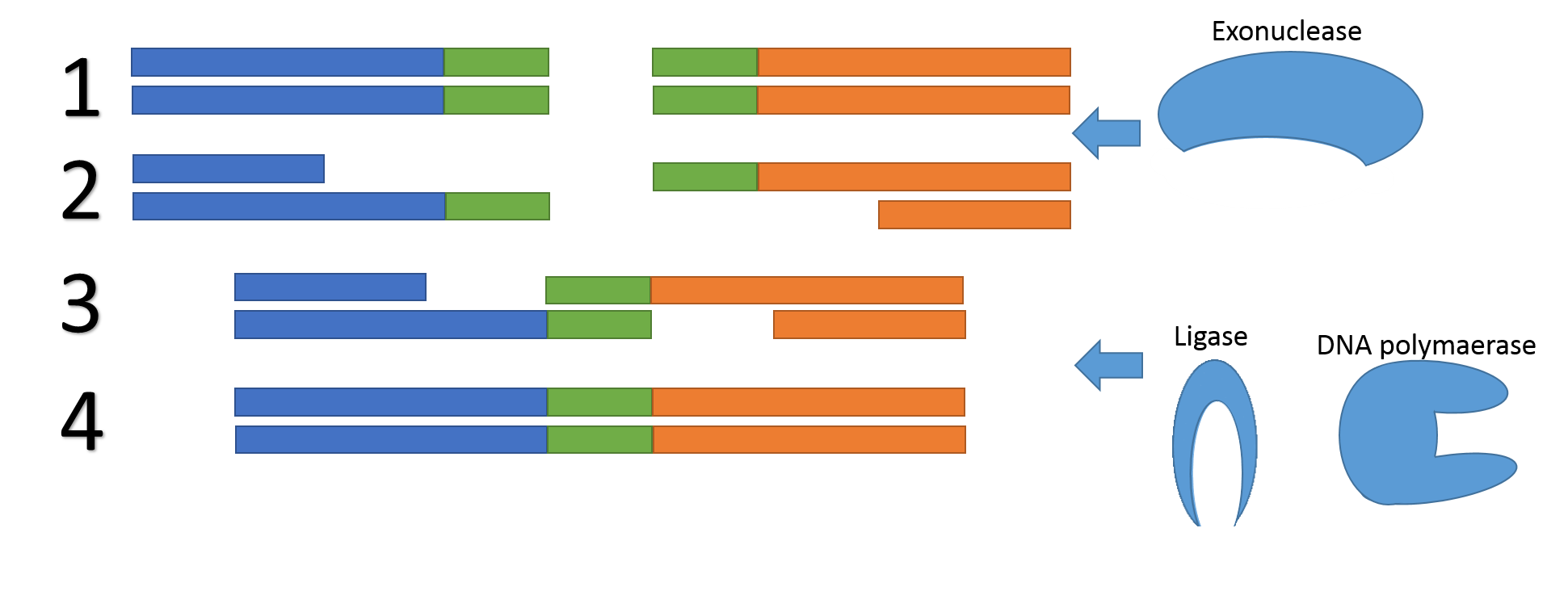

In 2009, a method was introduced which avoids potential problems associated with restriction sites and –enzymes, called Gibson assembly. The method utilizes sequence overlaps between the two DNA fragments to fuse them together. Unlike BioBrick assembly there are no requirements on the overlapping region which is one of the strengths of Gibson assembly

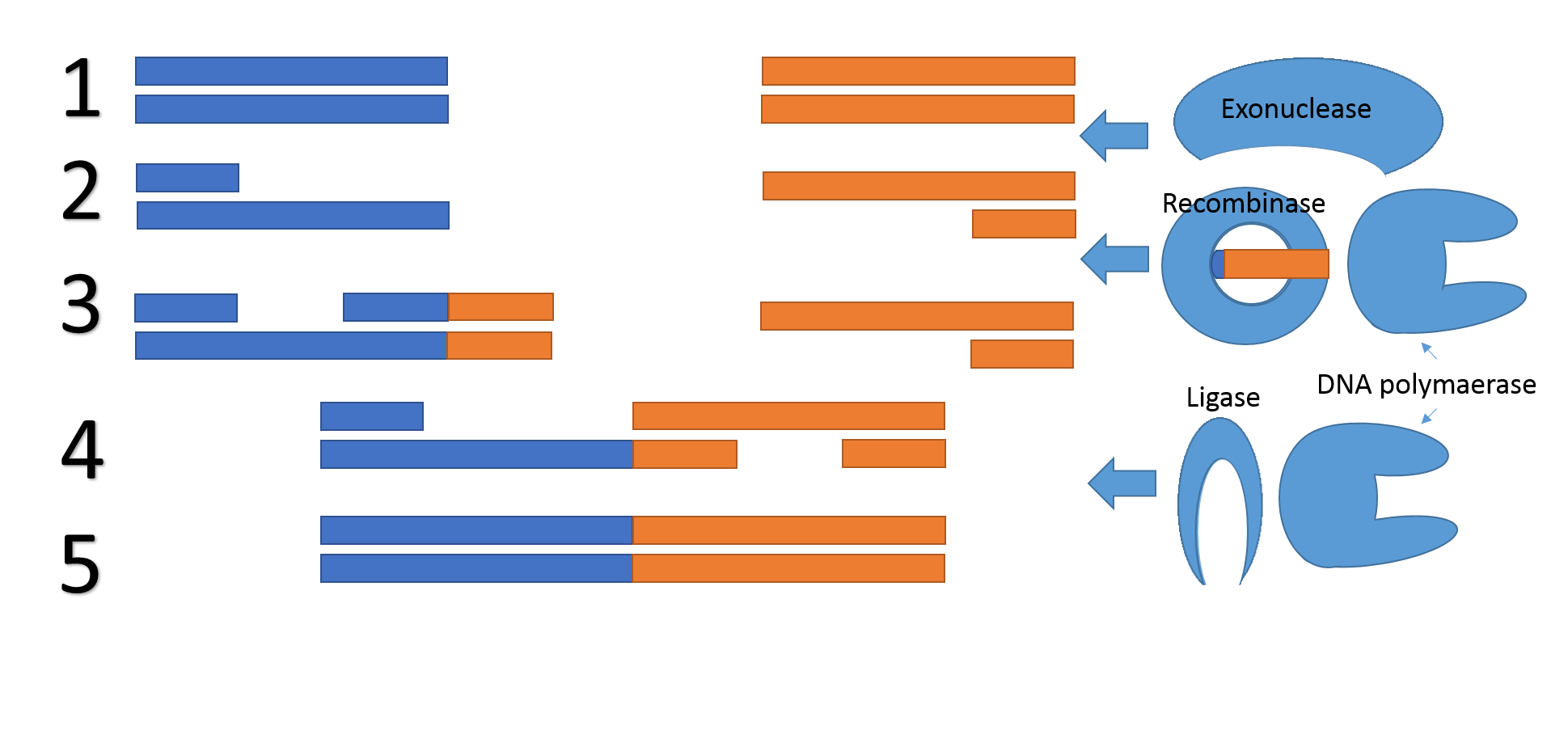

Figure 4, the mechanism of Gibson assembly. 1) An exonuclease chews of one of the two strands of the two DNA fragments (blue/green and orange/green). 2) The two fragments bind together due to their overlapping region (green). 3) A DNA polymerase fills in the gaps and a ligase repair the backbone nicks. 4) The DNA fragments are fused.

Now we introduce a concept for next generation of DNA assembly, Gibson 2.0. The concept is very similar to the normal Gibson assembly and is also compatible with normal Gibson reactions at the same time, but it removes the need for a specific overlap all together. The method is inspired by our repair mechanism and uses the normal Gibson proteins, but also a Recombinase and an oligonucleotide. The reason why no sequence overlap is needed is the exploitation of the recombinase and oligonucleotide to create an overlap during the reaction.

Figure 5, Mechanism for Gibson 2.0. 1) An exonuclease chews of one of the two complementary DNA strands on both of the DNA fragments. 2) One of the two DNA fragments is extended using the oligonucleotide as a reading frame. 3) The two fragments bind together due to their overlapping region 4) A DNA polymerase fills in the gaps and a ligase repair the backbone nicks. 5) The DNA fragments are fused.

Next generation marker

There is a wide range of laboratory markers available for use. Some of the most common markers confer resistance versus a specific chemical like antibiotic resistance. These markers are often very effective since the selective medium does not only kill the cells without the wanted DNA constructions, but it also kills potential contaminants. However, the use of antibiotics could potentially cause selective pressure for antibiotic resistance in pathogens if the antibiotics isn’t taken care of properly. If toxic chemicals are used, it could potential harm humans. Therefore extra safety measures need to be taken to combat these risks.

An alternative method is the use of auxotrophic markers, which is based on knocking out a protein in a pathway which synthesizes an essential biomolecule like a nucleotide or an amino acid. If the cells are grown on a complex nutrient medium, e.g. LB for E. coli or YPD for S. cerevisiae, the cells will survive. But if they are grown in a media without that specific biomolecule the only survivors will be the cells with the knocked out gene reinserted. The problem with auxotrophic markers could be mixing or contamination by another strain without that specific knockout.

Our concept for the next generation marker is based on our repair system. The used strain should have the needed parts for the repair system but one. During transformation/transfection the last repair protein should be added and then selection is done by irradiating the sample. The transformed cells would survive while the non-transformed cells would die. The same applies for eventual contaminants. So far it has the same effect as the chemical markers, but without the downsides of auxotrophic markers. However, since the irradiation causes no chemical waste handling it would be the more ethical choice.

Space applications

The next frontier, the border to the unexplored, space. Having sustainable production of resources is one of the big problems needing a solution before we start colonizing other planets. Mars is a possible candidate for colonization but it wouldn’t be easy. There is only a low abundance of oxygen and therefore ozone in the atmosphere. Without ozone, a lethal amount of UV radiation bombards the surface of Mars making most life from earth unable to survive. Another problem to life forms such us ours, is the lack of oxygen which leads to death by suffocation.

A solution for the colonizing would be to grow plants on mars, and when you have adult plants, then, it is only a matter of placing them in a synthetic environment like a dome. Humans could then possible live inside the dome.

All of this starts with developing a mechanism for plants to survive in high levels of UV. Some projects, like the one of our neighbor team UNIK Copenhagen (https://2015.igem.org/Team:UNIK_Copenhagen), are trying to design vegetation which survives on mars. They take a lot more survival factors than UV irradiation into an account, but our repair system could be one of the pieces needed for the final product.