Difference between revisions of "Team:Toronto/Results"

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

<li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Measurement"><span>measurement</span><i class="fa fa-bar-chart"></i></a></li> | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Measurement"><span>measurement</span><i class="fa fa-bar-chart"></i></a></li> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| − | <li><a href=" | + | <li><a href="#"><span>software</span><i class="fa fa-code"></i></a> |

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Software"><span>software</span></a></li> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| + | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Demo"><span>demo</span></a></li> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Generator"><span>wiki generator</span></a></li> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

<li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Entrepreneurship"><span>entrepreneurship</span><i class="fa fa-institution"></i></a></li> | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Entrepreneurship"><span>entrepreneurship</span><i class="fa fa-institution"></i></a></li> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

Revision as of 22:55, 19 November 2015

Project Results

Computational Biology Results

Here we present ConsortiaFlux, a framework for investigating and simulating the metabolism of microbial consortiums. ConsortiaFlux was created to explore communities of genome-scale metabolic models. We have created a tool that can provide insights in the metabolism of communities with an intuitive user interface and a novel community level flux balance analysis pipeline.

ConsortiaFlux automates the rendering of community metabolic networks, created by using HTML5 Canvas, where metabolites, reactions and species are represented as circles and metabolite-reaction relationships are represented as lines. Rendered networks dynamically move to a forced-layout by using the JavaScript library d3.js. The user interface allows the user to intuitively create community metabolic networks from a set of 32 bacterial species and subsequently add/remove metabolites and reactions; the user interface is created with Angular.js. All 32 bacterial metabolic models are genome-scale reconstructions published in literature. Parts from the iGEM registry can be added as reactions to the network. Upon initialization, metabolite networks display species nodes, external metabolites and external reactions where species nodes are connected to reactions that import/export metabolites in/out of the cell. Internal metabolites and reactions can be accessed by clicking the enter button which hovers over species nodes. The metabolism of the community can be simulated by pressing the optimize button.

Our tool simulates the community’s metabolism by using a community flux balance analysis pipeline we created using Python. We used COnstraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRApy) to optimize our models in Python. Our pipeline iteratively optimizes for individual genome-scale metabolic models for each species and computes/applies new constraints that exist in the community model. Once the constraints are calculated through iterations of linear programming and statistical procedures, a community model is built from the collection of species models where species are simply treated as additional compartments. The community model is then optimized with the community objective function. The community objective function is the summation of all the species’ objective functions where the shadow prices of metabolites are multiplied by a biomass coefficient determined from the iterations of linear programming and statistical procedures. Unlike traditional community flux balance analysis, our pipeline uses multiple iterations of linear programming instead of a bi-linear program (Khandelwal et al). The advantage of using our pipeline is that it can accommodate any number of species and that it uses linear systems.

We used ConsortiaFlux to simulate metabolism of the microbiome of oil sand tailings with the addition of our synthetic Escherichia coli that has the TodABCDEF genes which degrades toluene. With our community flux balance analysis pipeline, we saw an increase in the community biomass objective function compared to a community with E.coli that does not degrade toluene. [Then we just add in reactions that we saw an increase of flux].

This software can be applied in the future to many aspects of bacterial community studies, including numerous applications in human health and medicine. Our system of community flux balance analysis (cFBA) used the specific example of optimiziation for maximal toluene degradation within the microbial system of Athabasca oil sands tailings pond water, in order to best detoxify this water to be potable to inhabitants living downstream. However, the future uses for this tool could be far-reaching in nature.

This system has already been used for a wide range of projects including pinpointing pathogenicity islands in strains of bacteria which can be harmful to human populations (Raman and Chandra, 2009), assessing how rice plants can be optimized to best respond to flooding (Lakshmanan et al. 2013), and achieving spatiotemporal amalgamation of overall metabolism in other crop plants (Grafahrend-Belau et al. 2013). Even more significant achievements could prevail with this technology, such as further simple analysis of gut microbiomes in patients with gastrointestinal illness. With the future of cFBA and metabolic mapping, biological and medical research will no doubt leap forward with innovation.

Wetlab Results

Wetlab Goals:

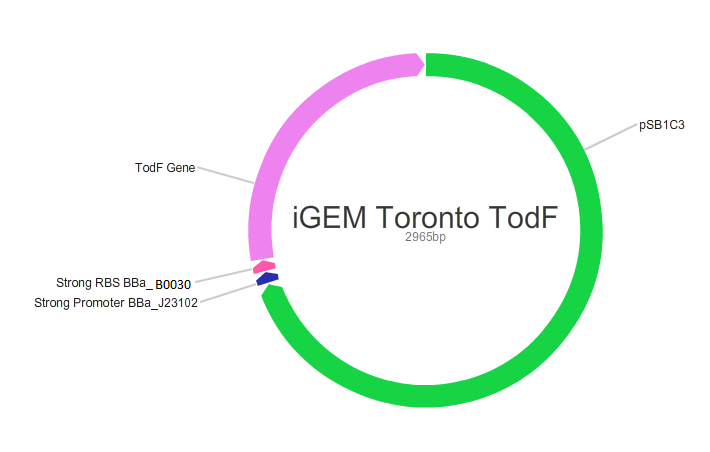

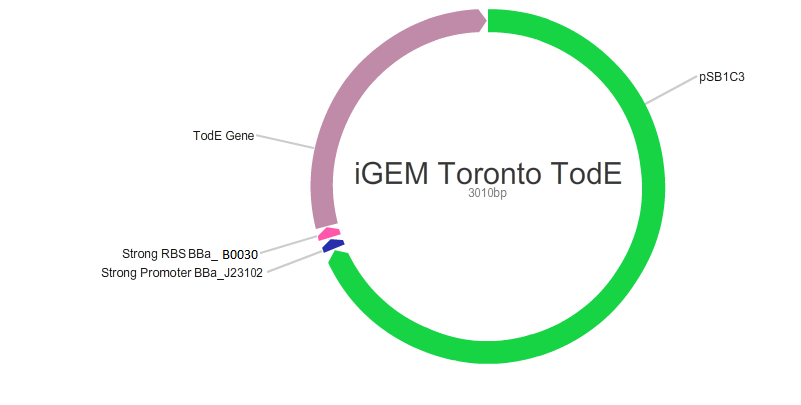

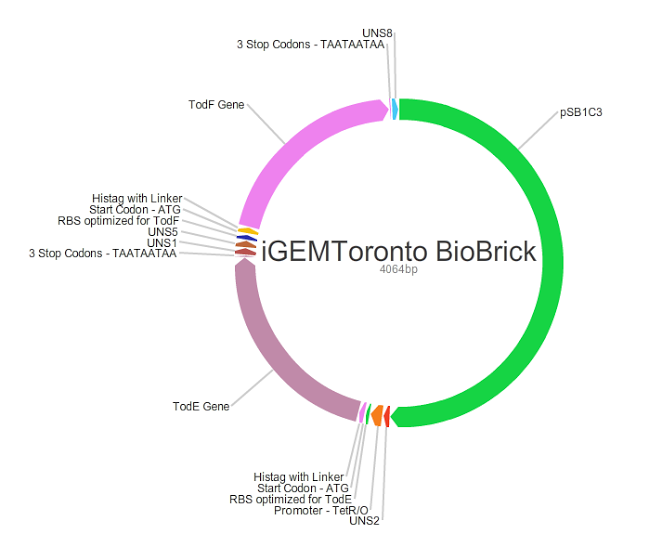

Our main goal in this project was to create standardized and easily customizable synthetic parts coding for the enzymes in the tod pathway, a toluene degrading pathway native to pseudomonas putida F1, in order to improve the efficiency of the pathway. We focused on the tod E (3-methyl catechol 2,3-dioxygenase) and tod F (HODA hydrolase) genes which appear to be important bottlenecks in the toluene degradation pathway. We are using E.Coli MG1655 as a model chassis since it contains the enzymes downstream of TodF in the pathway. As such, plasmid design had to be optimized for E.coli. This would be followed by the transformation of E.coli with the plasmid, the confirmation of protein formation by SDS PAGE and western blot (via His Tags) and the subsequent characterization of enzymatic activity. The characterization of TodE and TodF would be acheived via a spectrophotometric assay that would measure the change in the wavelength of 6-methyl HODA at 367nm. TodE would produce 6-methyl HODA and TodF would show consumption of the metabolite. This would be used to create a Michaeles-Mentens graph by transforming absorbance readings into concentrations by Beer's law. We subsequently also aimed to incorporate the complete toluene degradation pathway in E.coli to observe the complete degradation of toluene to carbon-dioxide and water. This would be achieved by co-transforming our plasmid with TodEF and TodABC1C2D (obtained from Dr. Zylstra).

Achieved:

Following are listed the goals we are able to accomplish Plasmid design:

- This was perhaps one of the most critical stages of the project since only a correctly designed plasmid would ultimately allow E.coli to successfully degrade toluene. For this purpose, we sought extensive guidance from our graduate and faculty supervisors who have had extensive experience in these areas. The plasmids were designed to be assembled by Gibson Assembly, Ligase Chain Reaction (LCR) and Synbiota Assembly. (A form of standardized digestion and ligation assembly)

Plasmid creation:

We were able to successfully create our plasmid by PCRing the psb1C3 backbone out of a plasmid containing BBa_J04450. Both TodE and TodF were made compatible for LCR by synthesizing UNS sequences (standard insulating ends) and by PCRing compatible ends for Gibson Assembly. The inserts were checked by using nanodrop readings and gel electrophoresis. At the same time, we needed to verify the correct assembly of our plasmid by digesting with specific enzyme and using gel electrophoresis to confirm the size. This was a bit challenging given that LCR was a new method of assembly and using gibson next to iGEM suffixes (multiple cloning sites) produced low efficiency. Standard protocols used in these experiments were not always completely effective so we had to modify our protocols to achieve the best possible results with respect to plasmid design. This did provide us with major insight regarding how standard protocols need to be modified in novel situations.E.coli transformation: We have been able to transform E.coli with our plasmid and we have obtained colonies on antibiotic selection media which indicates that our plasmids have been transformed.

Challenges faced:

Time Management:

This is where we struggled the most. This year we had recruited a fresh team and each member had to be trained in biosafety. At the same time the department had several administrative procedures that took long to clear and hence we were not able to work in lab on time. This has allowed us to formulate a concrete strategy for next year, so we can make best use of our time in the lab.Division of labour:

Due to the relative inexperience of many newer members in the lab, team leads had to take on the role of performing the tasks themselves. Higher efficiency was achieved by making a smaller, more select group to work on protocols throughout the week since large member base and low number of shifts per member led to discontinuity and confusion.

References:

Ramen and Chandra. Flux balance analysis of biological systems: Applications and challenges. Brief Bioinform, 10:4, pg.435-449. 2009.

Lakshmanan et al. Elucidating rice cell metabolism under flooding and drought stresses using flux-based modelling and analysis. Plant Physiology, 162:4, pg.2140-2150. 2013.

Grafahrend-Belau et al. Mutliscale metabolic modeling: Dynamic flux balance analysis on a whole-plant scale. Plant Physiology, 163:2, pg.637-647. 2013.