Difference between revisions of "Team:Toronto/Design"

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| − | <li><a href=" | + | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Parts"><span>parts</span><i class="fa fa-gear"></i></a></li> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Notebook"><span>notebook</span><i class="fa fa-book"></i></a></li> | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Notebook"><span>notebook</span><i class="fa fa-book"></i></a></li> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| Line 59: | Line 50: | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

<li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Safety"><span>safety</span><i class="fa fa-fire"></i></a></li> | <li><a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Toronto/Safety"><span>safety</span><i class="fa fa-fire"></i></a></li> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li><a href="#"><span>software</span><i class="fa fa-code"></i></a> | <li><a href="#"><span>software</span><i class="fa fa-code"></i></a> | ||

Latest revision as of 04:40, 20 November 2015

Bioreactor Design

The goal of our project is to sunthesize bacteria that can effectively degrade Toluene. At the same time we are aware of the safety concerns and public perception of introduction of synthetic organisms into the environment.

We have tried to address this issue in two ways:

- Public engagement and education about our project(mentioned in community-outreach.md)

- A Novel bioreactor design that can efficiently use bacteria to degrade toluene while keeping it separate from the environment.

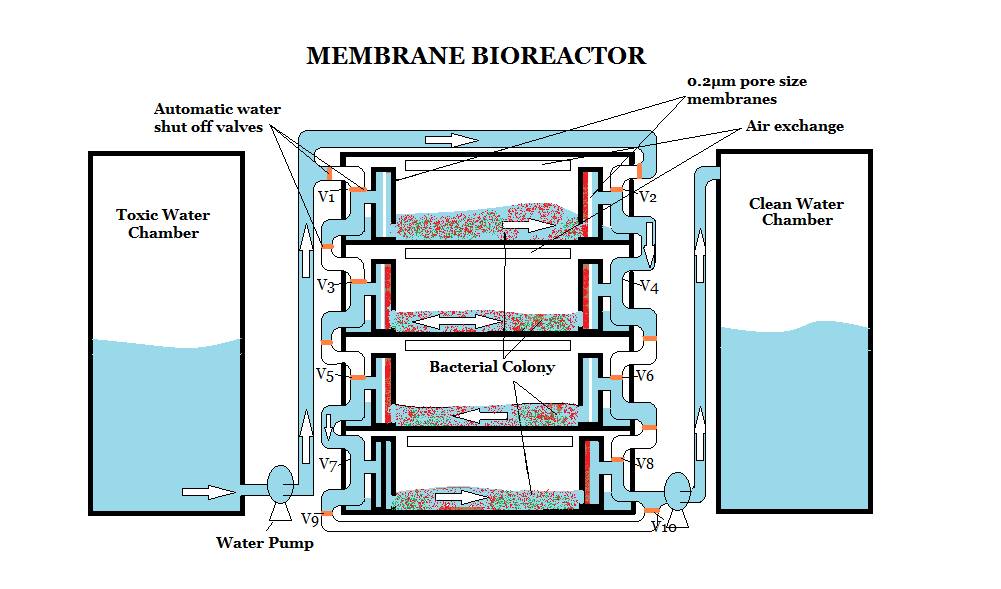

Above is the diagram for the membrane bioreactor.

Design:

As shown in the image the middle chamber is the reaction chamber, separated into multiple shelves. Each shelf has a discrete colony of bacteria(shown in red) along with natural bacteria(shown in green) that originally degraded toluene in the environment. On each side of the shelves we have a 0.2 µm pore size membrane. The purpose of these membranes is to confine bacteria into each compartment. The inlets and outlets of water on each side of the shelves is guarded by automatic water shut off valves.

How it works:

The toxic water is pumped into the reaction chamber from the top. The water enters into the first shelf through V1 or V2 valves – through V1 valve according to above diagram. The water is then allowed to stay in the chamber for a calculated amount of time, which is based on the time bacteria takes to degrade Toluene. After that time, water is allowed to go into the next chamber through V4 valve. Notice that water came into the chamber through V1 valve and travelled across the shelf to exit through V4 valve, which cause bacteria to clog the membrane on the right. The water is then allowed to stay into the second shelf for a specific time, to allow bacteria to degrade Toluene and later let into third shelf. Meanwhile, the first shelf has obtained a new load of water through V2 valve, which is later allowed to exit the shelf through V3 valve. This creates a two way flow of the water. The purpose of this two way flow of water is to reduce membrane fouling and biofilm formation by bacteria. Furthermore, the two way flow of water dislodges the bacteria from the membrane and spreads it back into the chamber, this allows better mixing of bacteria in the water which helps degrade Toluene effectively. The slits at the top of each shelf allow air exchange which gives a direct air contact with the surface of water in each shelf. The reason for this is to allow the bacterial colonies to have access to air which they would in the outside environment. Thus each shelf mimics the outside environment, this allows us to effectively apply community flux balance analysis to each shelf. The purpose of having multiple shelves is to increase the efficiency of degradation by having smaller loads of water in each chamber rather than having bulk amount of water in one chamber.

Prototype:

Our team has built a functional prototype of the bioreactor design shown above. We intend to demonstrate the working ability of our prototype during our presentation. However, for demonstration purposes we have chosen to not use bacteria since bacteria is not conspicous to the naked eye as well as we can not visually asses the effictiveness of the bacteria. Hence, we have decided to use beeds instead of bacteria, and wire gauze instead of 0.2 µm membranes. This would allow us to demonstarate the working ability of our bioreactor, however our prototype allows the use of bacteria and membranes in order to degrade Toluene.

Advantages over conventional bioreactor:

- Multi-stage purification of water allows thorough contact between bacteria and the water. Water being purified in multiple smaller loads of water is more effective than bulk amount of water with all the bacteria in it. Bulk amount of water with bacteria requires mixing of water.

- 0.2 µm pore size membranes allow no bacteria to escape each bacteria. Thus ensuring no bacteria enters fresh water.

- Better control – Automated gates control two way flow of water, ensuring no overflow of water in each shelf.

- Alternating flow - Two way flow of water in each shelf considerably reduce fouling and biofilm formation, since bacteria is shuffled back and forth in the shelf with each load of water.

- Non-conventional use of membranes – Membranes are primarily used to confine the bacteria in each shelf instead of conventional use of membranes (i.e filteration). Hence, considerably increasing the life span of membranes.

- Considerably low cost:

- No manual mixing of water required, since water goes through multiple stages of purification.

- Direct surface contact with air requires no addition of oxygen, since bioreactor does not need to be sealed.

- Cheaper maintenance – Due to alternating flow of water, the life span of membranes is considerably longer, hence requiring less maintenance.

Challenges faced and proposd solutions:

| Challenges | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|

| Direct air contact can allow volatile toxins to escape into the environment | We check the amount of toxins in water to not surpass the saturation point(by obtaining the top layer of water resting above thick cake of toxins). Hence, least amount of vapors are released in the air, which turns out to be negligible amount as per WHO standards. |

| Flux through micro-pore membrane | To obtain high flux through the membranes we will need to use light suction. However, we can increase the coss-sectional are of the membrane to increase flux |

Conclusion:

This novel design of bioreactor can confidently address the public concerns and safety issues of keeping synthetic bacteria separate from the water. Furthermore, it operates at lower cost while effectively degrading Toluene in comparison to conventional bioreactors.

References:

- World Health Organization. Toluene in drinking water: background document for development of WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality. 2004.

- L. van Dijk, G.Roncken, Membrane bioreactor for wastewater treatment: the state of the art and new developments. Water Science and Technology, 1997.35:10; pg.35-41

- Shah, Pranjul. Microfluidic bioreactors for culture of non-adherent cells

- Montseny, Emmanuel. Control of fed-batch bioreactors models by means of dynamic time-scale transformation and operatorial parametrization

- Gagliardo, P. Water reclamation with membrane bioreactors

- Chang et al. Carbon nutrition of Escherichia coli in the mouse intestine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004. 101:19, pp. 7427-7432