Difference between revisions of "Team:ETH Zurich/Project Description"

D.gerngross (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

<p>The first marker we are planning to detect is the increased production rate of lactate by cancer cells due to the Warburg effect, a metabolic shift occurring in tumor cells that is characterized by a much higher glycolysis rate and subsequent lactic acid production [<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Chen2007">Chen 2007</a>, <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Vander2009">Vander 2009</a>]. The increased output of L-lactate by cancer cells that results from this shift can be used to discriminate cancer cells from healthy cells. We found the lldPRD operon, which is endogenously present in <i>E. coli</i> to help it metabolize lactate, and decided to use this system to our advantage. The constitutive expression of LldR (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1847001">BBa_K1847001</a>), a repressor of the lldPRD operon in <i>E. coli</i>, is an important part of our system, since according to the literature, lldR acts as a repressor of promoters containing the respective lldR binding sites, the lldR operators O1 and O2. Upon exposure of <i>E. coli</i> to lactate, binding of lactate to LldR causes a conformational change, inhibiting lldR's ability to bind to its target operators, which in turn leads to activation of the operon [<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Aguilera2008">Aguilera 2008</a>]. | <p>The first marker we are planning to detect is the increased production rate of lactate by cancer cells due to the Warburg effect, a metabolic shift occurring in tumor cells that is characterized by a much higher glycolysis rate and subsequent lactic acid production [<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Chen2007">Chen 2007</a>, <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Vander2009">Vander 2009</a>]. The increased output of L-lactate by cancer cells that results from this shift can be used to discriminate cancer cells from healthy cells. We found the lldPRD operon, which is endogenously present in <i>E. coli</i> to help it metabolize lactate, and decided to use this system to our advantage. The constitutive expression of LldR (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1847001">BBa_K1847001</a>), a repressor of the lldPRD operon in <i>E. coli</i>, is an important part of our system, since according to the literature, lldR acts as a repressor of promoters containing the respective lldR binding sites, the lldR operators O1 and O2. Upon exposure of <i>E. coli</i> to lactate, binding of lactate to LldR causes a conformational change, inhibiting lldR's ability to bind to its target operators, which in turn leads to activation of the operon [<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Aguilera2008">Aguilera 2008</a>]. | ||

| − | <p>The concentration of lactate around the cells accumulates over time. Therefore, we designed our system to detect a fold-change using an incoherent feed-forward loop [<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Goentoro2009">Goentoro 2009</a>]. Overall, an <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Part_Collection">lldRO-lacO fusion promoter</a>, which we designed specifically for this setup, acts as a filter, detecting our first general cancer marker and converting it into a signal that will be crucial for the next step of our design, which will thus only induce a final output if elevated lactate production rates are detected. This is where the second cancer marker comes into play.</p> | + | <p>The concentration of lactate around the cells accumulates over time. Therefore, we designed our system to detect a fold-change using an incoherent feed-forward loop [<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Goentoro2009">Goentoro 2009</a>]. Overall, an <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Part_Collection#Double_responsive_promoter">lldRO-lacO fusion promoter</a>, which we designed specifically for this setup, acts as a filter, detecting our first general cancer marker and converting it into a signal that will be crucial for the next step of our design, which will thus only induce a final output if elevated lactate production rates are detected. This is where the second cancer marker comes into play.</p> |

Revision as of 00:48, 19 September 2015

- Project

- Modeling

- Lab

- Human

Practices - Parts

- About Us

A Microbial Beacon for Cancer Detection

Cancer as a major health concern

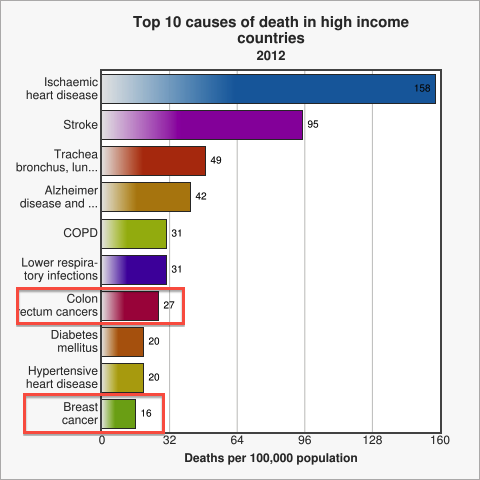

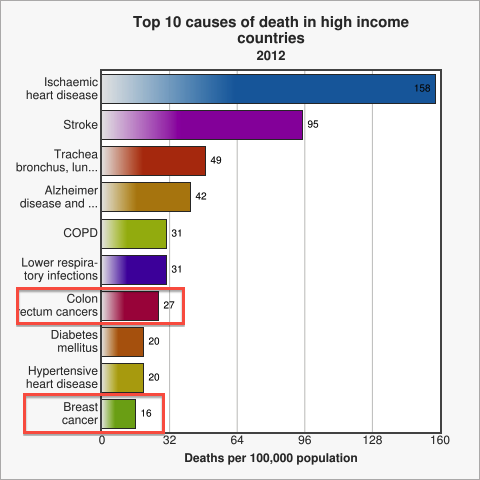

Figure 1. Cancer is a leading cause of death among high income countries. Image from WHO

Figure 1. Cancer is a leading cause of death among high income countries. Image from WHO

Cancer is among the top ten causes of death in developed countries [WHO]. Amongst all cancer patients, for approximately 90% the ultimate cause of death is metastasis [Saxe 2013], be it during the initial occurrence of cancer or at a time after successful treatment [Cooperberg 2009]. Therefore, early diagnosis of metastasis is one of modern medicine's major and challenging problems [WHO 2014]. Thus, designing a novel method to test for circulating cancer cells, which represent the first sign of possible metastasis [Sleijfer 2007], quickly caught our attention as a potential project idea. After researching current testing methods we decided to come up with a system for the assessment of metastasis risk in cancer patients and high-risk groups using a genetically engineered strain of Escherichia coli. The big advantage of a bacterial system over conventional analysis methods is the great capacity of signal integration in genetic circuits and the generation of a robust, yet sensitive output. Our engineered E. coli, called MicroBeacons, will provide a broadly applicable, cheap, and reliable alternative to existing test for circulating tumor cells (CTC).

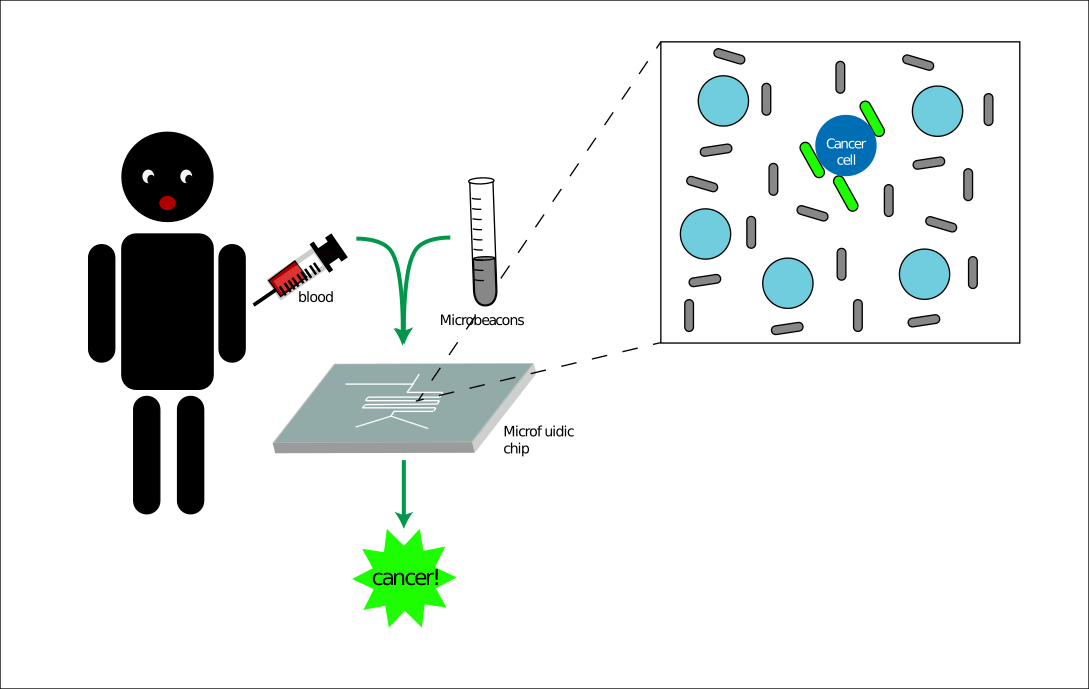

A universally applicable system for CTC detection

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) can be used as an indicator of the initial stages of metastasis [Sleijfer 2007]. In our project we aim to develop a novel method that is fast, economical, and reliable for the identification of CTCs by using MicroBeacons to detect two general cancer markers and indicate their co-occurrence through fluorescence. By design, this makes our system applicable to many types of cancer. To facilitate handling the cells, our detection system will be embedded in a microfluidic chip built especially for this purpose. In contrast to existing methods which rely on detection of very specific cancer markers, like epithelial cell adhesion molecules [Cooke 2001, Garcea 2005, Singhal 2005] a single general test would be more economical if it can be mass produced and deployed in a cost-effective manner.

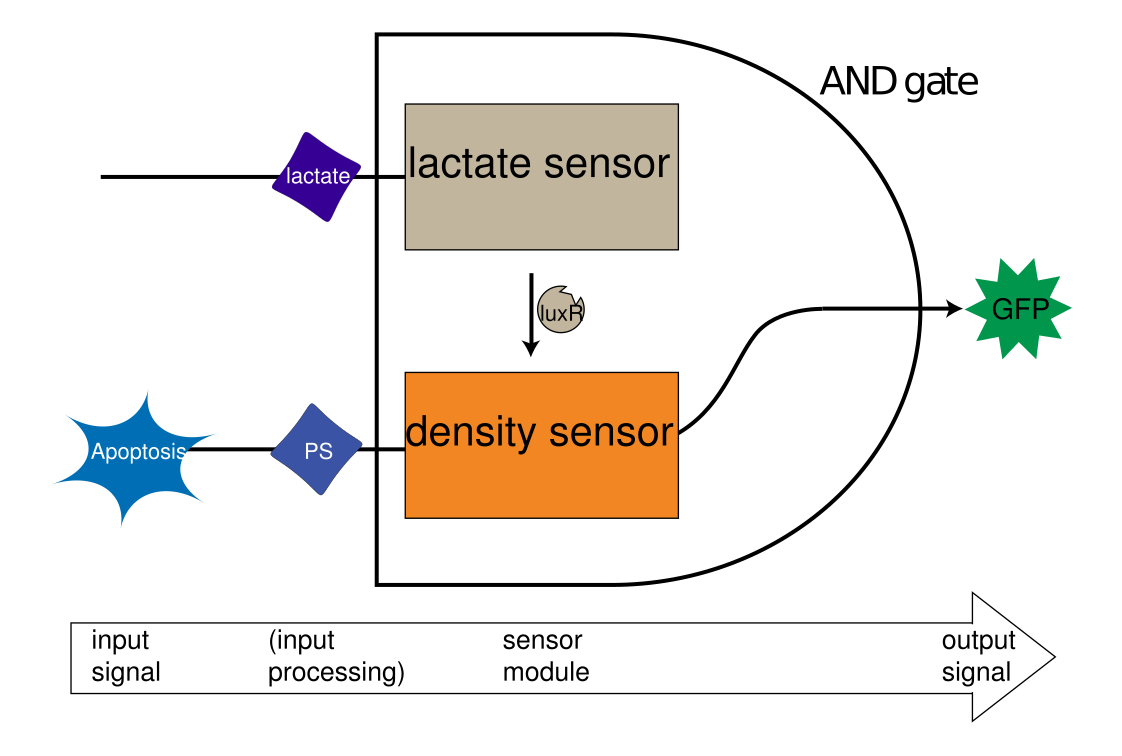

Higher selectivity thanks to AND gate

The elevated lactate production and binding of MicroBeacons on an apoptotic cell lead to a fluorescent signal. Both signals are chained in a way that quorum sensing can only be initiated upon detection of elevated lactate production rates. The final output of the system is the expression of reporter green fluorescent protein (GFP) coupled to this quorum sensing module (see densitiy sensor in figure below), which is only be expressed in significant levels near a target if it is a cancer cell.

Overall, the integration of two general markers allows for the detection of various types of cancers with high reliability and a low false positive rate, while control of signal expression by the bacteria should result in a considerable increase in the signal to noise ratio compared to conventional assay kits. The direct binding of our MicroBeacons to cancer cells allows for the detection of lactate and AHL in a controlled micro-environment with minimal crosstalk from other cells in the sample or unbound MicroBeacons. Finally, the use of a fluorescent signal as our output signal will allow for easy measurement from the microfluidic chip through microscopy.

Lactate sensor: Using cancer cells' metabolic adaptation to our advantage

The first marker we are planning to detect is the increased production rate of lactate by cancer cells due to the Warburg effect, a metabolic shift occurring in tumor cells that is characterized by a much higher glycolysis rate and subsequent lactic acid production [Chen 2007, Vander 2009]. The increased output of L-lactate by cancer cells that results from this shift can be used to discriminate cancer cells from healthy cells. We found the lldPRD operon, which is endogenously present in E. coli to help it metabolize lactate, and decided to use this system to our advantage. The constitutive expression of LldR (BBa_K1847001), a repressor of the lldPRD operon in E. coli, is an important part of our system, since according to the literature, lldR acts as a repressor of promoters containing the respective lldR binding sites, the lldR operators O1 and O2. Upon exposure of E. coli to lactate, binding of lactate to LldR causes a conformational change, inhibiting lldR's ability to bind to its target operators, which in turn leads to activation of the operon [Aguilera 2008].

The concentration of lactate around the cells accumulates over time. Therefore, we designed our system to detect a fold-change using an incoherent feed-forward loop [Goentoro 2009]. Overall, an lldRO-lacO fusion promoter, which we designed specifically for this setup, acts as a filter, detecting our first general cancer marker and converting it into a signal that will be crucial for the next step of our design, which will thus only induce a final output if elevated lactate production rates are detected. This is where the second cancer marker comes into play.

Density sensor: Bacteria as apoptosis detectors

To make our system reliable, we needed a second general cancer marker which would form an AND gate with the first marker. We encountered the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), or sTRAIL in its soluble form, which induces apoptosis specifically in cancer cells, leaving healthy cells unharmed [Srivastava 2001]. The initiation of apoptosis can be detected by the strong binding (Kd=0.5-1 nM) of Annexin V to phosphatidylserine (PS) that appears on the outer membrane of the target CTCs in early stages of apoptosis [Engeland 1998]. Although Annexin V is an intracellular protein in mammalian cells [Hawkins 2002], we planned to engineer it to be expressed on the surface of our MicroBeacons, allowing them to bind to the target CTCs. Binding of several MicroBeacons on the surface of an apoptotic CTC will be detected via quorum sensing signals.