Difference between revisions of "Team:Waterloo/Modeling/CaMV Biology"

(Created page with "{{Waterloo}} <html> <div class="container main-container"> <h1>Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) Biology</h1> <section id="genome" title="Lifecycle"> <p>Lifecycle Overvi...") |

|||

| (24 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

<h1>Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) Biology</h1> | <h1>Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) Biology</h1> | ||

| − | + | <p>Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) is a member of the caulimovirus genus of pararetroviruses. CaMV is an ideal virus for the study of CRISPR plant defense for several reasons. <ol> | |

| − | + | <li>Most importantly, CaMV only infects plants, making it significantly safer to work with.</li> | |

| − | + | <li>Second, it can infect <em>Arabidopsis thaliana</em>, the plant model organism for genetics, meaning many of the tools for genetic engineering already work.</li> | |

| − | + | <li>Finally, the CaMV genome is double stranded for much of the virus lifecycle, which means it can be easily targeted by CRISPR-Cas9 for cutting.</li> | |

| − | + | </ol> | |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | + | <section id="replication" title="Replication"> | |

| − | + | <h2>CaMV Replication</h2> | |

| − | <p></p> | + | <p>The lifecycle of a pararetrovirus such as CaMV is rather similar to that of a retrovirus such as HIV. Both types of viruses use a reverse transcriptase to turn viral mRNA into DNA. However, unlike retroviruses, pararetroviruses do not integrate into the host genome. Instead, thousands of minichromosomes of viral genome are imported into the nucleus, where they are transcribed by host machinery<cite ref="Hohn2013"></cite>.</p> |

| − | </section> | + | <p>Here we present a brief overview of the CaMV replication cycle, compiled from Khelifa et al. 2010 <cite ref="Khelifa2010"></cite>, Yasaka et al. 2014 <cite ref="Yasaka2014"></cite>, Hohn, Fütterera & Hull (1997) <cite ref="Hohn1997"></cite>, and Citovsky, Knorr, & Zambryski (1991) <cite ref="Citovsky1991"></cite>:</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-8"> | ||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <li>The virion enters the host cell, moves to the nuclear pore, and the viral genome is imported in the nucleus</li> | ||

| + | <li>Discontinuities in the genomes are repaired to form minichromosomes</li> | ||

| + | <li>Minichromosomes are used as templates to produce 35S RNA, 19S RNA, and 8S RNA</li> | ||

| + | <li>P6 is translated from 19S RNA and accumulates in electron-dense inclusion bodies (edIBs)</li> | ||

| + | <li>P6 transactivates production of P1-P5 from 35S RNA</li> | ||

| + | <li>Packaging occurs. The exact process is complicated, but either <cite ref="Hohn1997"></cite>:</li> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>35S RNA is packaged into virions along with P5 then is reverse transcribed within the capsid, or</li> | ||

| + | <li>35S RNA is reverse transcribed in the edIBs before packaging</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <li>The virion may either reinfect the nucleus to increase the copy number of the minichromosome (early in the infection) or it may leave the cell.</li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | <p>The team created an ordinary differential replication model of CaMV replication which is described on <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/CaMV_Replication">its own page</a>.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/e/ee/Waterloo_CaMV_Replication.gif" alt="CaMV Replication" style="max-width:300px;" class="img-responsive"/> | ||

| + | <div class="img-att"> | ||

| + | i | ||

| + | <ul class="img-att-bubble"> | ||

| + | <li>Photo © <a href="http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00136.x/full">Haas et al. (2005)</a></li> | ||

| + | <li>Figure 3 of <em>Cauliflower mosaic virus</em>: still in the news <cite ref="Haas2002"></cite></li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </section> | ||

| + | <section id="genome" title="Genome and Proteins"> | ||

| + | <h2>CaMV Genome and Proteins</h2> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The CaMV genome consists of circular, double-stranded DNA approximately 8000 bp in length <cite ref="Franck1980"></cite>. The genome contains three discontinuities typical of pararetroviruses <cite ref="Franck1980"></cite> <cite ref="Hohn2013"></cite>. Discontinuities are repaired within the nucleus to form covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) <cite ref="Khelifa2010"></cite>. There are seven open reading frames (ORFs) which code for six proteins of known function; P1-P6 (labeled gp2-gp7 in the diagram below) <cite ref="Khelifa2010"></cite> <cite ref="Hohn1997"></cite>. Two main RNAs are produced from cccDNA: pregenomic 35S RNA and subgenomic 19S RNA, as well as the small 8S RNA <cite ref="Guilley1982"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/4/46/Waterloo_Modeling_CaMV_Replication_Benchling_Genome.png" alt="CaMV Genome Visualization" style="width:500px;"/> | ||

| + | <figcaption>A Visualization of the CaMV Genome produced by importing the NCBI record into Benchling</figcaption> | ||

| + | <div class="img-att">i | ||

| + | <ul class="img-att-bubble"> | ||

| + | <li><a href="#">Link to original Photo</a></li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Details on the RNA transcripts and proteins produced by CaMV are given in the sections below.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="panel panel-default"> | ||

| + | <div class="panel-heading" role="tab" id="rna"> | ||

| + | <h3 class="panel-title"> | ||

| + | <a class="collapsed" role="button" data-toggle="collapse" data-parent="#bio background" href="#collapseRNA" aria-expanded="false" aria-controls="collapseRNA"> | ||

| + | RNA Transcripts | ||

| + | <span class="hidden-xs toggle-arrow pull-right">Panel Toggle</span> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </h3> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div id="collapseRNA" class="panel-collapse collapse" role="tabpanel" aria-labelledby="rna"> | ||

| + | <div class="panel-body"> | ||

| + | <h4>Pregenomic 35S RNA</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | 35S RNA is a complete transcript of the CaMV genome with additional 180 nt terminal repeats <cite ref="Guilley1982"></cite> <cite ref="Hohn1985"></cite>. It has two primary functions. The first is to act as an intermediate in genome replication. That is, it's reverse transcribed either in a viral factory or within the capsid to recover gapped dsDNA <cite ref="Pfeiffer1983"></cite>. It's second function is as polycistronic mRNA coding for P1-P5. Translation of P1-P5 from the 35S promoter must be transactivated by P6 <cite ref="Futterer1991"></cite>. 35S RNA also undergoes alternative splicing to regulate P1 and P2, which are potentially toxic in high enough concentrations <cite ref="Kiss-Laszlo1995"></cite> <cite ref="Froissart2004"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Subgenomic 19S RNA</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The 19S RNA is a 2.3 kb <cite ref="Covey1981"></cite> transcript which contains the ORF for P6 <cite ref="Khelifa2010"></cite>. P6 is constitutively produced from 19S RNA and it's many functions are described in it's own section. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>8S RNA</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | 8S RNA is 610-680 nt long <cite ref="Olszewski1983"></cite> and is transcribed from the leader sequence of 35S RNA. It's believed that it serves as a decoy for RNA interference, which normally targets the 35S leader <cite ref="Blevins2011"></cite> <cite ref="Hohn2015"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="panel panel-default"> | ||

| + | <div class="panel-heading" role="tab" id="pro"> | ||

| + | <h3 class="panel-title"> | ||

| + | <a class="collapsed" role="button" data-toggle="collapse" data-parent="#bio background" href="#collapseProtein" aria-expanded="false" aria-controls="collapseProtein"> | ||

| + | CaMV Proteins | ||

| + | <span class="hidden-xs toggle-arrow pull-right">Panel Toggle</span> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </h3> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div id="collapseProtein" class="panel-collapse collapse" role="tabpanel" aria-labelledby="rna"> | ||

| + | <div class="panel-body"> | ||

| + | <p>CaMV produces six proteins, five of which (P1-P5) are produced from the 35S RNA. The sixth, P6, is produced from the 19S RNA.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h4>Movement Protein (P1)</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The movement protein (MP) of CaMV facilitates intercellular spread of virions <cite ref="Lucas2006"></cite>. P1 binds to pectin methyltranferase, a cell wall associated protein <cite ref="Chen2000"></cite>, and ultimately forms intercellular tubules though which virions are transported to neighbouring cells <cite ref="Kastell1996"></cite>. This protein may also bind cooperatively to RNA to direct 35S and/or 19S RNA to neighbouring cells <cite ref="Citovsky1990"></cite>, which suggests the protein-RNA complex may also move between cells without a capsid. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Aphid Transmission Factor (P2)</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The aphid transmission factor (ATF) is a protein which allows for host-to-host transmission of the virus using aphids as vectors. P2 binds to the aphid stylets and P3, which allows virions to associate with the stylet upon feeding <cite ref="Drucker2002"></cite>. Its primary function is host-to-host transmission, but it does produce one electron-lucent inclusion body (elIB) which has minor effects on the system. To form the elIB, P2 associates with microtubules and are transported along the cytoskeleton to a central location. In this process some P3 associates with the P2 and is transported to the elIB <cite ref="Martiniere2009"></cite>. Finally, a small percent (~5%) of virions find their way to the elIB <cite ref="Bak2013"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Virion-Associated Protein (P3)</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The virion associated protein (VAP) is a 15 kDa protein is weakly associated with the viral capsid <cite ref="Mesnard1994"></cite>. It's implicated in both host-to-host <cite ref="Drucker2002"></cite> and cell-to-cell <cite ref="Kobayashi2002"></cite> transmission. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Capsid Protein (P4)</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The capsid protein (CP) is a precursor to numerous other polypeptides which we refer to as P4 subunits. The P4 subunits include P37, P44, P40, P80, P90, and P96, with P80 and P96 being homodimers composed of P37 and P44 respectively <cite ref="MartinezIzquierdo1987"></cite>. A viral capsid is formed from 420 subunits composed into 3 layers<cite ref="Cheng1992"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Reverse Transcriptase (P5)</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The P6 protein reverse transcribes 35S RNA to form partially double stranded DNA (pdsDNA) <cite ref="Pfeiffer1983"></cite>. The pdsDNA is then encapsidated by P4 subunits to produce virions. It's unknown if reverse transcription occurs within the capsid or in the viroplasm <cite ref="Hohn1997"></cite>. There is evidence that in Hepatitis B (a similar pararetrovirus) that RT first binds to the pregenome, then the RT-RNA complex is recognized by CP to form a capsid, after which reverse transcription finally occurs <cite ref="Ganem1993"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Transactivator/Viroplasmin Protein (P6)</h4> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The transactivator/viroplasmin protein (TAV), as it's name suggests, is a protein primarily involved in transactivating the five other proteins <cite ref="Futterer1991"></cite> and condenses into viroplasms <cite ref="Kobayashi2003"></cite>. The viroplasms, aka viral factories or electron-dense inclusion bodies (edIBs), sequester 35S RNA transcripts and produces the other proteins required for viral spread and assembly <cite ref="Mazzolini1989"></cite>. The purpose is two-fold: concentrating the nucleic acid and protein in a smaller volume to increase reaction rates, and protecting the replication machinery from cell defenses <cite ref="Mazzolini1989"></cite>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <section id="spread" title="Transport and Spread"> | ||

| + | <h2>Viral Transport and Spread</h2> | ||

| + | <p>CaMV exploits host transport mechanisms in order to spread. Neighbouring plant cells share cytoplasmic connections through connections called plasmodesmata. These symplastic connections are exploited by CaMV to spread to neighbouring cells, but it is a fairly slow process. The virions must travel between the plasma membrane and the desmotubule (cytoplasmic channel) of the plasmodesmata, a very narrow passage. The size of molecule able to diffuse through the plasmodesmata is determined by the size exclusion limit (SEL), which is affected by the gating properties of the plasmodesmata. In another slow cell-to-cell process, the virus can move through tubules formed through the cell wall. However, CaMV is able to spread to different regions of the plant quite quickly using the plant’s phloem (sugar-transport network). <cite ref="Carrington1996"></cite> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>In addition to exploiting the host transport machanisms, CaMV can induce the formation of microtubules in order to increase its rate of spread <cite ref="Carrington1996"></cite>. Microtubules are a key component of intercellular transmission as well as intracellular motion. They form viral inclusions that encourage uptake by aphids (the major plant-to-plant transport agent) and of viral factories <cite ref="Niehl2013"></cite>.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Modelling the spread of infection through a series of plant cells was the focus of the<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/Intercellular_Spread"> Intercellular Viral Spread Model</a>. </p> | ||

| + | </section> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <section id="defense" title="Plant Defenses"> | ||

| + | <h2>Natural Plant Defenses</h2> | ||

| + | <p>The CRISPR Plant Defense application aims to introduce a CRISPR/Cas9 as an antiviral defense in plants. Plants do, of course, have their own defenses against viral infection and we wanted to ensure that CRISPR/Cas9 provided <em>additional</em> defenses for the plants. To that end, two forms of natural plant defense were modelled: intercellular signalling and RNA interference. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Intercellular Defense Signalling</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Chemical signaling with chemicals such as salicylic acid (SA), NO and H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub> within plants is extremely important due to the huge role it plays in triggering and maintaining defense mechanisms to allow the plant cells to fight off pathogens. </p> | ||

| + | <p>The main plant defenses triggered by signalling are systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and the hypersensitive response (HR). SAR is a broad, long-term increased resistant to future infections, similar to the increased resistance against diseases in mammals post-infection. <cite ref="Ryals1994"></cite> This mechanism is only activated after a pathogen is detected within the plant, triggering defenses through signals like SA and NO. <cite ref="Klessig2000"></cite> During the initial wave of defense after pathogen detection, there is an “oxidative burst” wherein levels of oxidative species suddenly increase, accompanied by cell wall protein linkage, the activation of kinase and increased defensive gene expression. <cite ref="Klessig2000"></cite> </p> | ||

| + | <p>NO and SA play an interconnected role with each other, where reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as NO have been observed accumulating SA, and in turn, SA triggers ROS production (including NO and H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub>, the main signal for HR). <cite ref="Klessig2000"></cite> </p> | ||

| + | <p> In the hypersensitive response (HR), cells infected by a pathogen undergo apoptosis, forming lesions on the plant. H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>2</sub> allows for the localization of the HR-induced apoptosis by triggering the chemical processes required for cell degradation in addition to increasing the expression of defense genes, which it modulates during defense response <cite ref="Neill2002"></cite>. </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | HR and SAR are modeled extensively in the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/Intercellular_Spread">viral spread model</a> in order to produce a reasonable simulation of the infection of Arabidopsis Thaliana by CaMV. The different signalling chemicals have been simplified to one process each for HR and SAR, instead of having multiple reactions and interactions between chemicals, and are used to visualize the spread of the defenses throughout the plant. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>RNA Interference</h3> | ||

| + | <p>RNA interference is a method of gene silencing utilized in gene regulation and viral defense. Cytoplasmic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is cleaved by a Dicer-like enzyme (DCL) into short lengths, facilitated by a dsRNA-binding protein (DRB) <cite ref="Bagasra2004"></cite>. These short segments are called small interfering RNA (siRNA) or micro RNA (miRNA) and are approximately 20-25 base pairs with a 2-nucleotide overhang at the 3' end <cite ref="Siomi2009"></cite>. Specifically in <em>Arabidopsis thaliana</em>, DLC3 and DLC4 cleave CaMV virus-derived short interfering RNA (viRNA) into 24-nt and 21-nt long lengths respectively <cite ref="Haas2008"></cite>. The viRNA are split into single strands and integrated into a RNA-induced silencing complex, which targets and cleaves messenger RNA (mRNA). This prevents the use of mRNA in translation templates, effectively inhibiting gene expression <cite ref="Ahlquist2002"></cite>. To avoid this plant defense, P6 located in the nucleus interacts with DBR4 to eliminate Dicer activity <cite ref="Haas2008"></cite>. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>RNA interference is incorporated into the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/CaMV_Replication">CaMV Replication</a> and <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/Intercellular_Spread"> Intercellular Viral Spread Model</a>.</p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</section> | </section> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>References</h2> | ||

| + | <ol id="reflist"> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Waterloo_Footer}} |

Latest revision as of 02:24, 19 September 2015

Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) Biology

Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) is a member of the caulimovirus genus of pararetroviruses. CaMV is an ideal virus for the study of CRISPR plant defense for several reasons.

- Most importantly, CaMV only infects plants, making it significantly safer to work with.

- Second, it can infect Arabidopsis thaliana, the plant model organism for genetics, meaning many of the tools for genetic engineering already work.

- Finally, the CaMV genome is double stranded for much of the virus lifecycle, which means it can be easily targeted by CRISPR-Cas9 for cutting.

CaMV Replication

The lifecycle of a pararetrovirus such as CaMV is rather similar to that of a retrovirus such as HIV. Both types of viruses use a reverse transcriptase to turn viral mRNA into DNA. However, unlike retroviruses, pararetroviruses do not integrate into the host genome. Instead, thousands of minichromosomes of viral genome are imported into the nucleus, where they are transcribed by host machinery.

Here we present a brief overview of the CaMV replication cycle, compiled from Khelifa et al. 2010 , Yasaka et al. 2014 , Hohn, Fütterera & Hull (1997) , and Citovsky, Knorr, & Zambryski (1991) :

- The virion enters the host cell, moves to the nuclear pore, and the viral genome is imported in the nucleus

- Discontinuities in the genomes are repaired to form minichromosomes

- Minichromosomes are used as templates to produce 35S RNA, 19S RNA, and 8S RNA

- P6 is translated from 19S RNA and accumulates in electron-dense inclusion bodies (edIBs)

- P6 transactivates production of P1-P5 from 35S RNA

- Packaging occurs. The exact process is complicated, but either :

- 35S RNA is packaged into virions along with P5 then is reverse transcribed within the capsid, or

- 35S RNA is reverse transcribed in the edIBs before packaging

- The virion may either reinfect the nucleus to increase the copy number of the minichromosome (early in the infection) or it may leave the cell.

The team created an ordinary differential replication model of CaMV replication which is described on its own page.

- Photo © Haas et al. (2005)

- Figure 3 of Cauliflower mosaic virus: still in the news

CaMV Genome and Proteins

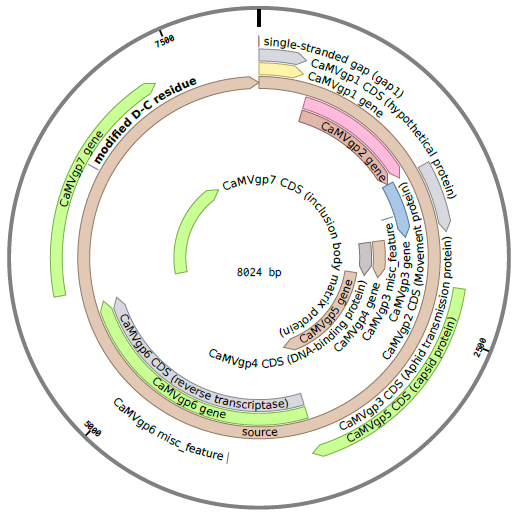

The CaMV genome consists of circular, double-stranded DNA approximately 8000 bp in length . The genome contains three discontinuities typical of pararetroviruses . Discontinuities are repaired within the nucleus to form covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) . There are seven open reading frames (ORFs) which code for six proteins of known function; P1-P6 (labeled gp2-gp7 in the diagram below) . Two main RNAs are produced from cccDNA: pregenomic 35S RNA and subgenomic 19S RNA, as well as the small 8S RNA .

Details on the RNA transcripts and proteins produced by CaMV are given in the sections below.

Pregenomic 35S RNA

35S RNA is a complete transcript of the CaMV genome with additional 180 nt terminal repeats . It has two primary functions. The first is to act as an intermediate in genome replication. That is, it's reverse transcribed either in a viral factory or within the capsid to recover gapped dsDNA . It's second function is as polycistronic mRNA coding for P1-P5. Translation of P1-P5 from the 35S promoter must be transactivated by P6 . 35S RNA also undergoes alternative splicing to regulate P1 and P2, which are potentially toxic in high enough concentrations .

Subgenomic 19S RNA

The 19S RNA is a 2.3 kb transcript which contains the ORF for P6 . P6 is constitutively produced from 19S RNA and it's many functions are described in it's own section.

8S RNA

8S RNA is 610-680 nt long and is transcribed from the leader sequence of 35S RNA. It's believed that it serves as a decoy for RNA interference, which normally targets the 35S leader .

CaMV produces six proteins, five of which (P1-P5) are produced from the 35S RNA. The sixth, P6, is produced from the 19S RNA.

Movement Protein (P1)

The movement protein (MP) of CaMV facilitates intercellular spread of virions . P1 binds to pectin methyltranferase, a cell wall associated protein , and ultimately forms intercellular tubules though which virions are transported to neighbouring cells . This protein may also bind cooperatively to RNA to direct 35S and/or 19S RNA to neighbouring cells , which suggests the protein-RNA complex may also move between cells without a capsid.

Aphid Transmission Factor (P2)

The aphid transmission factor (ATF) is a protein which allows for host-to-host transmission of the virus using aphids as vectors. P2 binds to the aphid stylets and P3, which allows virions to associate with the stylet upon feeding . Its primary function is host-to-host transmission, but it does produce one electron-lucent inclusion body (elIB) which has minor effects on the system. To form the elIB, P2 associates with microtubules and are transported along the cytoskeleton to a central location. In this process some P3 associates with the P2 and is transported to the elIB . Finally, a small percent (~5%) of virions find their way to the elIB .

Virion-Associated Protein (P3)

The virion associated protein (VAP) is a 15 kDa protein is weakly associated with the viral capsid . It's implicated in both host-to-host and cell-to-cell transmission.

Capsid Protein (P4)

The capsid protein (CP) is a precursor to numerous other polypeptides which we refer to as P4 subunits. The P4 subunits include P37, P44, P40, P80, P90, and P96, with P80 and P96 being homodimers composed of P37 and P44 respectively . A viral capsid is formed from 420 subunits composed into 3 layers.

Reverse Transcriptase (P5)

The P6 protein reverse transcribes 35S RNA to form partially double stranded DNA (pdsDNA) . The pdsDNA is then encapsidated by P4 subunits to produce virions. It's unknown if reverse transcription occurs within the capsid or in the viroplasm . There is evidence that in Hepatitis B (a similar pararetrovirus) that RT first binds to the pregenome, then the RT-RNA complex is recognized by CP to form a capsid, after which reverse transcription finally occurs .

Transactivator/Viroplasmin Protein (P6)

The transactivator/viroplasmin protein (TAV), as it's name suggests, is a protein primarily involved in transactivating the five other proteins and condenses into viroplasms . The viroplasms, aka viral factories or electron-dense inclusion bodies (edIBs), sequester 35S RNA transcripts and produces the other proteins required for viral spread and assembly . The purpose is two-fold: concentrating the nucleic acid and protein in a smaller volume to increase reaction rates, and protecting the replication machinery from cell defenses .

Viral Transport and Spread

CaMV exploits host transport mechanisms in order to spread. Neighbouring plant cells share cytoplasmic connections through connections called plasmodesmata. These symplastic connections are exploited by CaMV to spread to neighbouring cells, but it is a fairly slow process. The virions must travel between the plasma membrane and the desmotubule (cytoplasmic channel) of the plasmodesmata, a very narrow passage. The size of molecule able to diffuse through the plasmodesmata is determined by the size exclusion limit (SEL), which is affected by the gating properties of the plasmodesmata. In another slow cell-to-cell process, the virus can move through tubules formed through the cell wall. However, CaMV is able to spread to different regions of the plant quite quickly using the plant’s phloem (sugar-transport network).

In addition to exploiting the host transport machanisms, CaMV can induce the formation of microtubules in order to increase its rate of spread . Microtubules are a key component of intercellular transmission as well as intracellular motion. They form viral inclusions that encourage uptake by aphids (the major plant-to-plant transport agent) and of viral factories .

Modelling the spread of infection through a series of plant cells was the focus of the Intercellular Viral Spread Model.

Natural Plant Defenses

The CRISPR Plant Defense application aims to introduce a CRISPR/Cas9 as an antiviral defense in plants. Plants do, of course, have their own defenses against viral infection and we wanted to ensure that CRISPR/Cas9 provided additional defenses for the plants. To that end, two forms of natural plant defense were modelled: intercellular signalling and RNA interference.

Intercellular Defense Signalling

Chemical signaling with chemicals such as salicylic acid (SA), NO and H2O2 within plants is extremely important due to the huge role it plays in triggering and maintaining defense mechanisms to allow the plant cells to fight off pathogens.

The main plant defenses triggered by signalling are systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and the hypersensitive response (HR). SAR is a broad, long-term increased resistant to future infections, similar to the increased resistance against diseases in mammals post-infection. This mechanism is only activated after a pathogen is detected within the plant, triggering defenses through signals like SA and NO. During the initial wave of defense after pathogen detection, there is an “oxidative burst” wherein levels of oxidative species suddenly increase, accompanied by cell wall protein linkage, the activation of kinase and increased defensive gene expression.

NO and SA play an interconnected role with each other, where reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as NO have been observed accumulating SA, and in turn, SA triggers ROS production (including NO and H2O2, the main signal for HR).

In the hypersensitive response (HR), cells infected by a pathogen undergo apoptosis, forming lesions on the plant. H2O2 allows for the localization of the HR-induced apoptosis by triggering the chemical processes required for cell degradation in addition to increasing the expression of defense genes, which it modulates during defense response .

HR and SAR are modeled extensively in the viral spread model in order to produce a reasonable simulation of the infection of Arabidopsis Thaliana by CaMV. The different signalling chemicals have been simplified to one process each for HR and SAR, instead of having multiple reactions and interactions between chemicals, and are used to visualize the spread of the defenses throughout the plant.

RNA Interference

RNA interference is a method of gene silencing utilized in gene regulation and viral defense. Cytoplasmic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is cleaved by a Dicer-like enzyme (DCL) into short lengths, facilitated by a dsRNA-binding protein (DRB) . These short segments are called small interfering RNA (siRNA) or micro RNA (miRNA) and are approximately 20-25 base pairs with a 2-nucleotide overhang at the 3' end . Specifically in Arabidopsis thaliana, DLC3 and DLC4 cleave CaMV virus-derived short interfering RNA (viRNA) into 24-nt and 21-nt long lengths respectively . The viRNA are split into single strands and integrated into a RNA-induced silencing complex, which targets and cleaves messenger RNA (mRNA). This prevents the use of mRNA in translation templates, effectively inhibiting gene expression . To avoid this plant defense, P6 located in the nucleus interacts with DBR4 to eliminate Dicer activity .

RNA interference is incorporated into the CaMV Replication and Intercellular Viral Spread Model.