Difference between revisions of "Team:ETH Zurich/Modeling/Reaction-diffusion"

| (279 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ETH_Zurich}} | {{ETH_Zurich}} | ||

| + | {{:Template:ETH_Zurich/mathJax}} | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <div class="expContainer"> | + | <div class="expContainer" style=position:relative> |

<h1>Reaction-diffusion Models</h1> | <h1>Reaction-diffusion Models</h1> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--[if gte IE 9]><!--> | ||

| + | <!--<div class="imgBox">--> | ||

| + | <object class="svg" data="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/c/c1/Reaction_diffusion_model.svg" type="image/svg+xml" width="12%"> | ||

| + | </object> | ||

| + | <!--</div>--> | ||

| + | <!--<![endif]--> | ||

| + | <!--[if lte IE 8]> | ||

| + | <![endif]--> | ||

| + | |||

<h2>Introduction</h2> | <h2>Introduction</h2> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>One of the two signals used by our <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Glossary#Circulating_Tumor_Cell__CTC_">CTC</a> detection system is the detection of apoptotic cancer cells through <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Glossary#Quorum_sensing">quorum sensing</a> between <i>E. coli</i> cells colocalized around them. However, for this to be a useful signal as part of an <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Glossary#">AND gate</a>, <i>E. coli</i> within the same experimental environment (in our case, a well) as a mammalian cell (henceforth called the <b>target cell</b>) must only trigger the loop if they are colocalized and the cell produces a high amount of lactate, or at least trigger after a sufficient amount of time. By accurately simulating the diffusion of the two chemical species AHL and lactate through the environment, the efficacy of our quorum sensing module as a signal of colocalization can be assessed. |

| − | + | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The results from these simulations show that due to the small size of the well in which the experiment takes place, the generation of a slightly higher AHL concentration around the target cell is only possible due to the strong binding of LuxR to AHL. Unbound AHL diffuses through a 1 nL well in about 6 minutes, thus quickly diminishing its concentration gradient. However, the greater capture of lactate by cells bound to the target cell relative to free-floating cells creates a concentration gradient of LuxR which translates to a difference in GFP signal between bound and unbound cells. Combinatorially testing cases where <i>E. coli</i> cells bind or float around high- or low-rate lactate producers shows that our system acts as an AND gate of the two cancer markers, with <i>E. coli</i> bound to a high lactate producer fluorescing at a greater strength and the other cases exhibiting intermediate levels of fluorescence. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="highlightBox"> | ||

| + | <h3>Goals</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | We need to use a reaction-diffusion model to fully understand the diffusion of the intercellular chemical species, and hence, our system's functionality. Through this modeling, we aim to explore</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>the diffusion of AHL and lactate through the well</li> | ||

| + | <li>the self-activation time of the system in different well volumes</li> | ||

| + | <li>the relative capture of secreted lactate by bound and unbound <i>E. coli</i></li> | ||

| + | <li>the influence of <a href="#Logistic_growth_of_E__coli">logistic growth</a> of the <i>E. coli</i> on the activation time</li> | ||

| + | <li>simulation of the system in a water droplet suspended in an oil flow</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<div class="expContainer"> | <div class="expContainer"> | ||

| − | <h2>" | + | <h2>The "doughnut" model</h2> |

| + | <h3>Model development</h3> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ETH_doughnut_schem.svg | thumb | <b>Figure 1.</b> Schematic of the "doughnut" model. Lactate is produced by the the target cell in the middle and captured at a certain rate by doughnut <i>E. coli</i>. AHL is produced by the <i>E. coli</i> and freely diffuses through all domains.]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | For a simulation of the diffusion of chemical species to be meaningful, a geometry accurately representing the distributions of the cells within the well is required. Preliminary simulations were done in a geometry where a central circle representing the target cell was surrounded with smaller circles representing bound <i>E. coli</i> and circles uniformly distributed in the remaining space represented unbound <i>E. coli</i>. It was quickly realized, however, that this would not be an accurate representation due to the rapid growth of the <i>E. coli</i> population. To address this, the discrete circles were abstracted to a geometry with three connected domains representing populations of <i>E. coli</i> with different cell densities. Owing to the shape of the layer of bound <i>E. coli</i> in two-dimensions, this geometry is referred to as the <b>"doughnut" model</b>. A simplification of this model known as the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/Single-cell_Model"><b>compartment model</b></a> was also implemented in MATLAB and used for further analysis. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| − | < | + | <h3>Abstraction of discrete <i>E. coli</i> to a connected space</h3> |

| − | < | + | </html> |

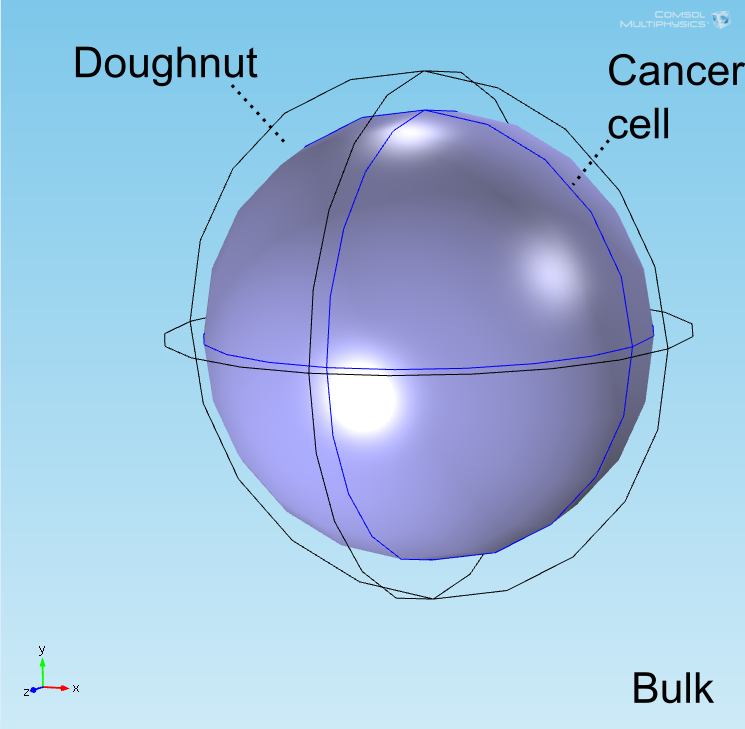

| − | < | + | [[File:ETH_doughnut.png | thumb | <b>Figure 2.</b> Doughnut and cancer cell represented as spheres in a model in COMSOL Multiphysics.]] |

| − | </ | + | <html> |

| − | + | ||

| − | < | + | <p>The well in which our reaction takes place is a box of length 100μm representing a well of volume 1 nL in the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Chip">chip</a>. In the middle of the well, a sphere represents the target cell and is surrounded by a layer whose thickness is the diameter of an <i>E. coli</i> cell representing the space taken up by the bound <i>E. coli</i> (called the <b>doughnut</b>) (see Figure 1). Finally, the remaining space represents both the medium and free-floating <i>E. coli</i> cells, which we refer to as the <b>bulk</b>. All chemical species are able to diffuse within their domains, while AHL and lactate are able to diffuse across domain boundaries. The <i>E. coli</i> population in the bulk grows logistically, represented by an increase in the domain's density, and hence reaction rates, over time. |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>The well in which our reaction takes place is a box of length | + | |

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="info"> | <div class="info"> | ||

<h4>Assumptions</h4> | <h4>Assumptions</h4> | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| − | <li> | + | <li>One non-dividing target cell per well</li> |

| − | + | <li>Uniform distribution of <i>E. coli</i> cells in their respective domains</li> | |

| − | <li> | + | <li>The doughnut has the density of the maximum number of cells that can bind to it</li> |

| − | <li> | + | <li>A cell unbinding from the target is immediately replaced, so cell density in the doughnut is constant</li> |

| − | + | <li><a href="#Logistic_growth_of_E__coli">Logistic growth</a> of <i>E. coli</i> in the bulk with a doubling time of 30 minutes</li> | |

| − | <li> | + | <li><i>E. coli</i> take up lactate, but do not export it</li> |

| − | < | + | |

| − | < | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <li> | + | |

</ol> | </ol> | ||

<a class="expander" href="#" onclick="expand(this);return false;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/1f/Blank_square.png"></a> | <a class="expander" href="#" onclick="expand(this);return false;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/1f/Blank_square.png"></a> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <p>The lactate and AHL modules were modeled and analyzed separately before being merged into a combined model. Since the <a href="#Lactate_Module">lactate module</a> does not export and chemical species, most of its analysis is identical to that from the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/Lactate_Module">single-cell lactate module</a> page. Thus, in the following section, analysis is restricted to a study of the relative amounts of lactate that are taken up by cells within the doughnut and bulk. In the <a href="#AHL_Module">AHL module</a>, we study the activation times of the system in the domains under different conditions. In addition, we assess the effects of the increasing density of <i>E. coli</i> in the bulk over time and the influence of performing the experiment in a <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Chip#Introduction_and_first_idea">water droplet suspended in a flow of oil</a>. The <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/Single-cell_Model">combined model</a> is used to determine the system's final GFP production rate and determine of the system acts as an AND gate on its two inputs. |

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="expContainer"> | ||

| + | <h2>Lactate Module</h2> | ||

| + | <h3>Lactate uptake by cells</h3> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ETH_lact_prod.eps.svg|thumb|right|<b>Figure 3.</b> Lactate produced by cancer and normal mammalian cells. Both functions have the same steady-state, but cancer cells produce lactate at three times the rate.]] | ||

| + | [[File:ETH_captured_lactate.svg|thumb|right|<b>Figure 4.</b> Lactate captured from a cancer cell by <i>E. coli</i> in the doughnut and the bulk. Doughnut cells capture lactate until its internal concentration is 20 times the outside concentration.]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | |||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | High rates of lactate production by a target cell do not readily translate to equal intracellular concentrations in the <i>E. coli</i> cells. In particular, those cells within the doughnut domain will capture a greater fraction of the excreted lactate due to its higher apparent concentration immediately around the target cell. Therefore, a simulation of the diffusion of lactate through the well and its capture by <i>E. coli</i> will provide a better idea of the input for our sensor. Due to the dilution of lactate upon diffusion into the bulk and to reduce computational complexity, it is assumed that all lactate entering the bulk is taken up by the bulk <i>E. coli</i>. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | + | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | As shown in Figure 4, the uptake and excretion rates set for lactate lead to a 20:1 ratio of lactate concentration between the doughnut and the bulk, as described in <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Dong1993">[Dong, <i>et al.</i>, 1993]</a>. Lactate is excreted by the target cell until the total amount produced would have corresponded to a concentration of 700 μ M had it not been excreted. | |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="expContainer"> | |

| − | + | <h2>AHL Module</h2> | |

| + | <p>For these simulations, it is assumed that all <i>E. coli</i> cells contain a constant amount of total LuxR corresponding to the magnitude of the peak produced by the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/Lactate_Module">single-cell lactate module</a>. This represents a worst-case test of the system to study its intrinsic propensity to self-activate</p> | ||

| + | <h3>Diffusion of AHL and self-activation time with logistic population growth vs. constant population</h3> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ETH_AHL_per_cell.gif|thumb|right|<b>Figure 5.</b> Per-cell AHL concentration in the well. The capturing of AHL by LuxR produces short-lived higher concentrations of AHL in the doughnut. (click to view animation)]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | To test the diffusion time of AHL and to obtain baseline self-activation times for the system, simulations were run with a constant bulk population size of 1000 <i>E. coli</i> cells. Despite the orders-of-magnitude difference in the diffusion coefficients of AHL through water and across cell membranes, the diffusion of AHL across the well still takes place on the order of a few minutes. In wells of volumes 1 nL, 10 nL, and 100 nL, the AHL concentration reaches a sufficient concentration to activate the system in 10 minutes, x minutes, and y minutes, respectively. Thus, a 100 nL well is sufficient to differentiate between wells with colocalized and floating cell populations. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | One of the assumptions made in the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/AHL_Module">AHL module</a> to test worst-case behavior was that the bulk is maximally populated with <i>E. coli</i>. More accurately, we can model the growth of an initial population in the bulk. Suppose we start with an initial <i>E. coli</i> population corresponding to an optical density of \(OD_{600}=0.1\) and a carrying capacity corresponding to \(OD_{600}=2\), with a doubling time of 30 minutes. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Relative to the trials with a constant population of bulk <i>E. coli</i>, no difference in activation time was observed for the doughnut cells or the cells in the 10 nL well. The only difference was observed in the bulk cells in a 100 nL well, where activation occurred approximately 20 minutes earlier. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div> | ||

| + | <ul style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_AHL_activation_time.eps.svg|thumb|none|310px|<b>Figure 6.</b> Activation times of the AHL module in different domains under different conditions.]]</li> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_logG_activation_time.svg|thumb|none|310px|<b>Figure 7.</b> Activation of the AHL module at 10 nL and 100 nL with a logistically growing population.]]</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <h3>Nanoliter well with constant velocity flow</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Although the original testing environment of <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Chip#Introduction_and_first_idea">water droplets suspended in a flow of oil</a> could not be put into practice due to time constraints, a simulation of this setup was done to predict how it would have affected our results. Having a constant velocity flow in a channel with an open boundary with the well is equivalent to increasing the well's volume, thus, should result in similar effects. However, the apparent volume of the system may become so large that the system never triggers regardless of lactate input. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="imgBox" style="width:100%"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2015.igem.org/File:ETH_microfluidics_flow.svg"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/9/9d/ETH_microfluidics_flow.svg" style="width:100%"> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 8.</b> Schematic of a microfluidic chip with a water droplet trapped in a well and a channel of flowing oil above.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ETH_GFP_flow.svg|thumb|right|<b>Figure 9.</b> GFP per cell when a flow is applied]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| − | + | <p> | |

| − | + | When this environment was simulated on a well of volume 1 nL, a shift in the activation time occurred corresponding to running the system in a well orders of magnitude greater than 100 nL. This model demonstrates that with the amount of LuxR that is present in the system, the combined effect of LuxR capturing AHL and the diffusion rate of AHL out of the doughnut is sufficient to not change the activation time of the system in that domain. In the bulk, on the other hand, due to the absence of this slower diffusion coefficient, the activation of the system is delayed. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div><ul style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_GFP_per_cell.gif|thumb|none|310px|<b>Figure 9A.</b> Spatiotemportal plot GFP per cell with flow (click to view animation)]]</li> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_AHL_per_cell_flow.gif|thumb|none|310px|<b>Figure 9B.</b> Spatiotemportal plot AHL per cell with flow (click to view animation)]]</li> | ||

| + | </ul></div> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="expContainer"> | ||

| + | <h2>Full Model</h2> | ||

| + | <h3>An AND gate of the signals</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | When the lactate and AHL modules are combined, including the effects of AHL and lactate diffusion, lactate capture, and <i>E. coli</i> population growth, the response of the system on its two inputs in this more accurate model can be assessed. Rather than representing the two inputs as continuous variables as shown in the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/Single-cell_Model">compartment model</a>, they are represented in four discrete states</p> | ||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <li>High lactate production rate (cancer cell), doughnut of bound bacteria (<b>ON-ON</b>)</li> | ||

| + | <li>High lactate production rate, no binding of bacteria (<b>ON-OFF</b>)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Normal lactate production rate (normal cell), doughnut of bound bacteria (<b>OFF-ON</b>)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Normal lactate production rate, no binding of bacteria (<b>OFF-OFF</b>)</li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | <p>From figures 10 and 11, it is clear that the environment in which both signals are present triggers the system, whereas a delayed and lower-amplitude response is produced by the system in which the bacteria colocalize around a normal cell. Consistent with the results from the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/Modeling/Single-cell_Model">compartment model</a>, the OFF-ON trial is an intermediate between the ON-ON and OFF-OFF states. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <ul style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_GFP_percell_everything.gif|thumb|none|320px|<b>Figure 10.</b> Spatiotemporal plot of GFP production in the doughnut and the bulk (click to view the animation)]]</li> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_GFP_everything_noflow.svg|thumb|none|320px|<b>Figure 11.</b> Plot of GFP production in the four test cases. The OFF-ON case is an intermediate between the ON-ON and OFF-OFF case.]]</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div class="info" style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <h3>Concentrations detected by microscopy</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | All modeling results previously have reported the concentrations of the chemical species within a single cell in its respective environment, either in the doughnut or the bulk. However, when our detection system is implemented in a chip, the total concentration of GFP within a domain will be measured and not the per-cell concentration. This dilution effect of the apparent concentration means that reported concentrations in the bulk will differ from what has been simulated due to the low density of cells in the bulk. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | When the concentration of GFP is corrected for this dilution effect, the signal ratio between the ON-ON and all other cases increased by a factor of 200. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="imgBox"> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <ul style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">A) [[File:ETH_GFP_ratios.eps.svg|frameless|none|300px]]</li> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">B) [[File:ETH_GFP_ratios_micro.eps.svg|frameless|none|300px]]</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 12.</b> Ratios of GFP concentration between the ON-ON trial and all others. A) Per-cell ratios B) Microscopy concentration ratios.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <a class="expander" href="#" onclick="expand(this);return false;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/1f/Blank_square.png"></a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Simulation of the full model in a flow</h3> | ||

| + | <div class="info"> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Although the introduction of the flow improved the outlook of the AHL module by reducing the propensity of the system in the bulk <i>E. coli</i> from self-activating, that module did not take into account the effects that the introduction of a flow would have on the diffusion and transport of lactate. As evidenced by the plots below, the amount of lactate taken up by the doughnut <i>E. coli</i> is reduced by an order of magnitude, prevent the system from activating under any conditions. The outflux of lactate from the well greatly reduces the extracellular concentration of lactate, increasing the diffusion of lactate through the doughnut domain and reducing the amount of lactate those cells are able to take up. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="imgBox"> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <ul style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_GFP_everything_flow.svg|frameless|none|220px]]</li> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_lact_everything.eps.svg|frameless|none|220px]]</li> | ||

| + | <li style="display: inline-block;">[[File:ETH_LuxR_everything.eps.svg|frameless|none|220px]]</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 13.</b> Per-cell concentrations of GFP, captured lactate, and LuxR when an environment with a water droplet suspended in oil is simulated. The diffusion of lactate and AHL out of the well the amounts that can be captured, preventing the system from activating.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <a class="expander" href="#" onclick="expand(this);return false;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/1f/Blank_square.png"></a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="expContainer"> | ||

| + | <h2>Summary</h2> | ||

| + | <p>By modeling the diffusion of lactate through our well, we have demonstrated that the <i>E. coli</i> bound to their target cell, through active transport and capture by binding to LldR, reduce the accessible lactate concentration of the unbound cells, producing a concentration gradient of its output signal LuxR.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Simulations of the AHL module demonstrated that the leakiness of the LuxR promoter leads to the self-activation of this module within our experiment's timeframe and this activation time is increased by both increasing the volume of the well and introducing a laminar flow above the well to flush out AHL and lactate. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>In the full model, the cells bound to a cancer cell activated the earliest and produced the strongest GFP signal, while the other cases produced intermediate levels. When the full system is run with a flow above the well, the flushing of AHL and lactate out of the system reduces the amounts of these species that can be captured by the cells and the system does not activate. However, the actual system most likely does not function as implemented, since the diffusion of lactate and AHL out of the water droplet is most likely low enough that its concentration at the oil-water interface will be sufficiently large to make the assumption of a zero-concentration boundary condition invalid. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | One major feature that could not be implemented fully due to time constraints was a more accurate model of the binding and unbinding of <i>E. coli</i> to the target cell. All models have assumed that this binding has already happened and that a cell that has bound does not unbind. During the experiment, however, the initial dynamics of the system when the <i>E. coli</i> have not fully populated the bulk could affect the final GFP concentrations. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="expContainer"> | ||

| + | <h2>Model Details</h2> | ||

| + | <h3>Logistic growth of <i>E. coli</i></h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Let us define \(n_\text{bulk}:[0,t_\text{sim}]\longrightarrow \mathbb N\) as the function representing the size of the <i>E. coli</i> population in the bulk at time \(t\), with an initial population size of \(n_0\), a carrying capacity of \(K\), and a growth rate of \(R\). The closed-form equation of this function is then | ||

| + | $$n_\text{bulk}(t) = \frac{n_0 K e^{Rt}}{K + n_0(e^{Rt}-1)}$$ | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="info"> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | If we denote the doubling time of the population by \(t_2\), we can solve for the growth rate \(R\) and define a new constant \(g\) s.t. | ||

| + | $$R = \frac{\log2 + \log(K+n_0) - \log(K-2n_0)}{t_2} =: \frac{\log g}{t_2}$$ | ||

| + | When we plug this value back into the original equation, it simplifies to | ||

| + | $$n_\text{bulk}(t) = \frac{n_0 K g^{\frac{t}{t_2}}}{K + n_0(g^{\frac{t}{t_2}}-1)}$$ | ||

| + | Finally, if we define the time we end our experiment, denoted \(t_\text{sim}\), as the time when the population reaches size \((1-\varepsilon)K\) for some small \(\varepsilon>0\), then we can solve for \(t_\text{sim}\) | ||

| + | $$t_\text{sim} = \frac{1}{R}\log\frac{(K-n_0)(1-\varepsilon)}{n_0\varepsilon}$$ | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h4>Carrying capacity</h4> | ||

| + | <p>The <a href="">experimental results</a> showed that the final optical density of the <i>E. coli</i> colonies was around \(OD_{600}=2\). Given the linear relation of cell and optical density, the carrying capacity of the cells in the 1 nL well was computed as \(1598\) cells.</p> | ||

| + | <a class="expander" href="#" onclick="expand(this);return false;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/1f/Blank_square.png"></a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<h3>Diffusion and transport of chemical species</h3> | <h3>Diffusion and transport of chemical species</h3> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | <i>E. coli</i> actively import lactate via a proton-motive symporter lldP.[<a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Nunez2002">Nunez, 2002</a>] Thus, a cross-membrane transport reaction had to be implemented. Since diffusion across barriers is implemented with equal diffusion coefficients for both directions in COMSOL, the transport of lactate across the doughnut membrane was implemented by modeling two different states of unbound lactate. If we let our reference space be the interior of the doughnut, we can define two pseudo-species \(Lact_\text{in}\) and \(Lact_\text{out}\), denoting intracellular and extracellular lactate, respectively. \(Lact_\text{out}\) is produced by the target cell and can diffuse freely though the medium and all membranes, while \(Lact_\text{in}\) is converted irreversibly from \(Lact_\text{out}\) and cannot diffuse out. | |

$$ | $$ | ||

| − | + | Lact_\text{out} \mathop{\mathop{\xrightarrow{\hspace{4em}}}^{\xleftarrow{\hspace{4em}}}}^{k_{\mathrm{ext}}}_{k_\text{int}} | |

| − | + | Lact_\text{in} | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

$$ | $$ | ||

| − | + | Only the \(Lact_\text{in}\) state can react with the other chemical species in the doughnut and only \(Lact_\text{out}\) can react with other chemical species in the bulk. The value of \(k_\text{ext}\) was estimated based on <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Dong1993">[Dong, <i>et al.</i>, 1993]</a>, while \(k_\text{int}\) was set to maintain a \(k_\text{ext}:k_\text{int}\) ratio of 20:1 <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Dong1993">[Dong, <i>et al.</i>, 1993]</a>. | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | AHL | + | Since AHL can freely diffuse across membranes, unbound AHL is only modeled as one state that can diffuse across all barriers. The effective diffusion coefficient of lactate was estimated relative its coefficient in water \(D_{aq}\) by the relation |

$$\frac{D_e}{D_{aq}}\approx 0.25$$ | $$\frac{D_e}{D_{aq}}\approx 0.25$$ | ||

| + | using the approximation proposed in a 2003 review by <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Stewart2003">Stewart.</a> The diffusion coefficient of AHL through the membrane was computed from an AHL excretion rate of \(D_m = 100 \text{min}^{-1}\) <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/References#Kaplan1985">[Kaplan, <i>et al.</i>, 1985]</a>. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <h3> | + | |

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Correcting concentrations</h3> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | Since <i>E. coli</i> are not fully packed into the domains in our model, a concentration correction has to be applied to the chemical species. If no correction is made for the strictly intracellular species, then the reported concentrations are single-cell. To compensate for the fact that AHL can diffuse across membranes, its production rate is scaled by the ratio of the total <i>E. coli</i> volume and the volume of the domain they are present in. Although this relation assumes instant diffusion of AHL, the small volume of the well makes this assumption approximately hold on our simulation timescale. | |

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | < | + | <h3>Implementing flow using boundary conditions</h3> |

| − | </ | + | <p> |

| − | < | + | Since it is assumed that the presence of a constant flow of fluid on the top boundary of a well will draw away all of the free-floating molecules, this was implemented as a 0-concentration boundary condition on the top of the well. |

| − | < | + | </p> |

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Simulation in COMSOL Multiphysics</h3> | ||

| + | <p>All simulations were run with 1000 time steps and a course mesh. For the full model, the course mesh led to convergence issues in the nonlinear solver, so a normal mesh was used.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| + | {{:Template:ETH_Zurich/footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:42, 19 September 2015

- Project

- Modeling

- Lab

- Human

Practices - Parts

- About Us

Reaction-diffusion Models

Introduction

One of the two signals used by our CTC detection system is the detection of apoptotic cancer cells through quorum sensing between E. coli cells colocalized around them. However, for this to be a useful signal as part of an AND gate, E. coli within the same experimental environment (in our case, a well) as a mammalian cell (henceforth called the target cell) must only trigger the loop if they are colocalized and the cell produces a high amount of lactate, or at least trigger after a sufficient amount of time. By accurately simulating the diffusion of the two chemical species AHL and lactate through the environment, the efficacy of our quorum sensing module as a signal of colocalization can be assessed.

The results from these simulations show that due to the small size of the well in which the experiment takes place, the generation of a slightly higher AHL concentration around the target cell is only possible due to the strong binding of LuxR to AHL. Unbound AHL diffuses through a 1 nL well in about 6 minutes, thus quickly diminishing its concentration gradient. However, the greater capture of lactate by cells bound to the target cell relative to free-floating cells creates a concentration gradient of LuxR which translates to a difference in GFP signal between bound and unbound cells. Combinatorially testing cases where E. coli cells bind or float around high- or low-rate lactate producers shows that our system acts as an AND gate of the two cancer markers, with E. coli bound to a high lactate producer fluorescing at a greater strength and the other cases exhibiting intermediate levels of fluorescence.

Goals

We need to use a reaction-diffusion model to fully understand the diffusion of the intercellular chemical species, and hence, our system's functionality. Through this modeling, we aim to explore

- the diffusion of AHL and lactate through the well

- the self-activation time of the system in different well volumes

- the relative capture of secreted lactate by bound and unbound E. coli

- the influence of logistic growth of the E. coli on the activation time

- simulation of the system in a water droplet suspended in an oil flow

The "doughnut" model

Model development

For a simulation of the diffusion of chemical species to be meaningful, a geometry accurately representing the distributions of the cells within the well is required. Preliminary simulations were done in a geometry where a central circle representing the target cell was surrounded with smaller circles representing bound E. coli and circles uniformly distributed in the remaining space represented unbound E. coli. It was quickly realized, however, that this would not be an accurate representation due to the rapid growth of the E. coli population. To address this, the discrete circles were abstracted to a geometry with three connected domains representing populations of E. coli with different cell densities. Owing to the shape of the layer of bound E. coli in two-dimensions, this geometry is referred to as the "doughnut" model. A simplification of this model known as the compartment model was also implemented in MATLAB and used for further analysis.

Abstraction of discrete E. coli to a connected space

The well in which our reaction takes place is a box of length 100μm representing a well of volume 1 nL in the chip. In the middle of the well, a sphere represents the target cell and is surrounded by a layer whose thickness is the diameter of an E. coli cell representing the space taken up by the bound E. coli (called the doughnut) (see Figure 1). Finally, the remaining space represents both the medium and free-floating E. coli cells, which we refer to as the bulk. All chemical species are able to diffuse within their domains, while AHL and lactate are able to diffuse across domain boundaries. The E. coli population in the bulk grows logistically, represented by an increase in the domain's density, and hence reaction rates, over time.

Assumptions

- One non-dividing target cell per well

- Uniform distribution of E. coli cells in their respective domains

- The doughnut has the density of the maximum number of cells that can bind to it

- A cell unbinding from the target is immediately replaced, so cell density in the doughnut is constant

- Logistic growth of E. coli in the bulk with a doubling time of 30 minutes

- E. coli take up lactate, but do not export it

The lactate and AHL modules were modeled and analyzed separately before being merged into a combined model. Since the lactate module does not export and chemical species, most of its analysis is identical to that from the single-cell lactate module page. Thus, in the following section, analysis is restricted to a study of the relative amounts of lactate that are taken up by cells within the doughnut and bulk. In the AHL module, we study the activation times of the system in the domains under different conditions. In addition, we assess the effects of the increasing density of E. coli in the bulk over time and the influence of performing the experiment in a water droplet suspended in a flow of oil. The combined model is used to determine the system's final GFP production rate and determine of the system acts as an AND gate on its two inputs.

Lactate Module

Lactate uptake by cells

High rates of lactate production by a target cell do not readily translate to equal intracellular concentrations in the E. coli cells. In particular, those cells within the doughnut domain will capture a greater fraction of the excreted lactate due to its higher apparent concentration immediately around the target cell. Therefore, a simulation of the diffusion of lactate through the well and its capture by E. coli will provide a better idea of the input for our sensor. Due to the dilution of lactate upon diffusion into the bulk and to reduce computational complexity, it is assumed that all lactate entering the bulk is taken up by the bulk E. coli.

As shown in Figure 4, the uptake and excretion rates set for lactate lead to a 20:1 ratio of lactate concentration between the doughnut and the bulk, as described in [Dong, et al., 1993]. Lactate is excreted by the target cell until the total amount produced would have corresponded to a concentration of 700 μ M had it not been excreted.

AHL Module

For these simulations, it is assumed that all E. coli cells contain a constant amount of total LuxR corresponding to the magnitude of the peak produced by the single-cell lactate module. This represents a worst-case test of the system to study its intrinsic propensity to self-activate

Diffusion of AHL and self-activation time with logistic population growth vs. constant population

To test the diffusion time of AHL and to obtain baseline self-activation times for the system, simulations were run with a constant bulk population size of 1000 E. coli cells. Despite the orders-of-magnitude difference in the diffusion coefficients of AHL through water and across cell membranes, the diffusion of AHL across the well still takes place on the order of a few minutes. In wells of volumes 1 nL, 10 nL, and 100 nL, the AHL concentration reaches a sufficient concentration to activate the system in 10 minutes, x minutes, and y minutes, respectively. Thus, a 100 nL well is sufficient to differentiate between wells with colocalized and floating cell populations.

One of the assumptions made in the AHL module to test worst-case behavior was that the bulk is maximally populated with E. coli. More accurately, we can model the growth of an initial population in the bulk. Suppose we start with an initial E. coli population corresponding to an optical density of \(OD_{600}=0.1\) and a carrying capacity corresponding to \(OD_{600}=2\), with a doubling time of 30 minutes.

Relative to the trials with a constant population of bulk E. coli, no difference in activation time was observed for the doughnut cells or the cells in the 10 nL well. The only difference was observed in the bulk cells in a 100 nL well, where activation occurred approximately 20 minutes earlier.

Nanoliter well with constant velocity flow

Although the original testing environment of water droplets suspended in a flow of oil could not be put into practice due to time constraints, a simulation of this setup was done to predict how it would have affected our results. Having a constant velocity flow in a channel with an open boundary with the well is equivalent to increasing the well's volume, thus, should result in similar effects. However, the apparent volume of the system may become so large that the system never triggers regardless of lactate input.

Figure 8. Schematic of a microfluidic chip with a water droplet trapped in a well and a channel of flowing oil above.

When this environment was simulated on a well of volume 1 nL, a shift in the activation time occurred corresponding to running the system in a well orders of magnitude greater than 100 nL. This model demonstrates that with the amount of LuxR that is present in the system, the combined effect of LuxR capturing AHL and the diffusion rate of AHL out of the doughnut is sufficient to not change the activation time of the system in that domain. In the bulk, on the other hand, due to the absence of this slower diffusion coefficient, the activation of the system is delayed.

Full Model

An AND gate of the signals

When the lactate and AHL modules are combined, including the effects of AHL and lactate diffusion, lactate capture, and E. coli population growth, the response of the system on its two inputs in this more accurate model can be assessed. Rather than representing the two inputs as continuous variables as shown in the compartment model, they are represented in four discrete states

- High lactate production rate (cancer cell), doughnut of bound bacteria (ON-ON)

- High lactate production rate, no binding of bacteria (ON-OFF)

- Normal lactate production rate (normal cell), doughnut of bound bacteria (OFF-ON)

- Normal lactate production rate, no binding of bacteria (OFF-OFF)

From figures 10 and 11, it is clear that the environment in which both signals are present triggers the system, whereas a delayed and lower-amplitude response is produced by the system in which the bacteria colocalize around a normal cell. Consistent with the results from the compartment model, the OFF-ON trial is an intermediate between the ON-ON and OFF-OFF states.

Concentrations detected by microscopy

All modeling results previously have reported the concentrations of the chemical species within a single cell in its respective environment, either in the doughnut or the bulk. However, when our detection system is implemented in a chip, the total concentration of GFP within a domain will be measured and not the per-cell concentration. This dilution effect of the apparent concentration means that reported concentrations in the bulk will differ from what has been simulated due to the low density of cells in the bulk.

When the concentration of GFP is corrected for this dilution effect, the signal ratio between the ON-ON and all other cases increased by a factor of 200.

- A) Error creating thumbnail: File missing

- B) Error creating thumbnail: File missing

Figure 12. Ratios of GFP concentration between the ON-ON trial and all others. A) Per-cell ratios B) Microscopy concentration ratios.

Simulation of the full model in a flow

Although the introduction of the flow improved the outlook of the AHL module by reducing the propensity of the system in the bulk E. coli from self-activating, that module did not take into account the effects that the introduction of a flow would have on the diffusion and transport of lactate. As evidenced by the plots below, the amount of lactate taken up by the doughnut E. coli is reduced by an order of magnitude, prevent the system from activating under any conditions. The outflux of lactate from the well greatly reduces the extracellular concentration of lactate, increasing the diffusion of lactate through the doughnut domain and reducing the amount of lactate those cells are able to take up.

- Error creating thumbnail: File missing

- Error creating thumbnail: File missing

- Error creating thumbnail: File missing

Figure 13. Per-cell concentrations of GFP, captured lactate, and LuxR when an environment with a water droplet suspended in oil is simulated. The diffusion of lactate and AHL out of the well the amounts that can be captured, preventing the system from activating.

Summary

By modeling the diffusion of lactate through our well, we have demonstrated that the E. coli bound to their target cell, through active transport and capture by binding to LldR, reduce the accessible lactate concentration of the unbound cells, producing a concentration gradient of its output signal LuxR.

Simulations of the AHL module demonstrated that the leakiness of the LuxR promoter leads to the self-activation of this module within our experiment's timeframe and this activation time is increased by both increasing the volume of the well and introducing a laminar flow above the well to flush out AHL and lactate.

In the full model, the cells bound to a cancer cell activated the earliest and produced the strongest GFP signal, while the other cases produced intermediate levels. When the full system is run with a flow above the well, the flushing of AHL and lactate out of the system reduces the amounts of these species that can be captured by the cells and the system does not activate. However, the actual system most likely does not function as implemented, since the diffusion of lactate and AHL out of the water droplet is most likely low enough that its concentration at the oil-water interface will be sufficiently large to make the assumption of a zero-concentration boundary condition invalid.

One major feature that could not be implemented fully due to time constraints was a more accurate model of the binding and unbinding of E. coli to the target cell. All models have assumed that this binding has already happened and that a cell that has bound does not unbind. During the experiment, however, the initial dynamics of the system when the E. coli have not fully populated the bulk could affect the final GFP concentrations.

Model Details

Logistic growth of E. coli

Let us define \(n_\text{bulk}:[0,t_\text{sim}]\longrightarrow \mathbb N\) as the function representing the size of the E. coli population in the bulk at time \(t\), with an initial population size of \(n_0\), a carrying capacity of \(K\), and a growth rate of \(R\). The closed-form equation of this function is then $$n_\text{bulk}(t) = \frac{n_0 K e^{Rt}}{K + n_0(e^{Rt}-1)}$$

If we denote the doubling time of the population by \(t_2\), we can solve for the growth rate \(R\) and define a new constant \(g\) s.t. $$R = \frac{\log2 + \log(K+n_0) - \log(K-2n_0)}{t_2} =: \frac{\log g}{t_2}$$ When we plug this value back into the original equation, it simplifies to $$n_\text{bulk}(t) = \frac{n_0 K g^{\frac{t}{t_2}}}{K + n_0(g^{\frac{t}{t_2}}-1)}$$ Finally, if we define the time we end our experiment, denoted \(t_\text{sim}\), as the time when the population reaches size \((1-\varepsilon)K\) for some small \(\varepsilon>0\), then we can solve for \(t_\text{sim}\) $$t_\text{sim} = \frac{1}{R}\log\frac{(K-n_0)(1-\varepsilon)}{n_0\varepsilon}$$

Carrying capacity

The experimental results showed that the final optical density of the E. coli colonies was around \(OD_{600}=2\). Given the linear relation of cell and optical density, the carrying capacity of the cells in the 1 nL well was computed as \(1598\) cells.

Diffusion and transport of chemical species

E. coli actively import lactate via a proton-motive symporter lldP.[Nunez, 2002] Thus, a cross-membrane transport reaction had to be implemented. Since diffusion across barriers is implemented with equal diffusion coefficients for both directions in COMSOL, the transport of lactate across the doughnut membrane was implemented by modeling two different states of unbound lactate. If we let our reference space be the interior of the doughnut, we can define two pseudo-species \(Lact_\text{in}\) and \(Lact_\text{out}\), denoting intracellular and extracellular lactate, respectively. \(Lact_\text{out}\) is produced by the target cell and can diffuse freely though the medium and all membranes, while \(Lact_\text{in}\) is converted irreversibly from \(Lact_\text{out}\) and cannot diffuse out. $$ Lact_\text{out} \mathop{\mathop{\xrightarrow{\hspace{4em}}}^{\xleftarrow{\hspace{4em}}}}^{k_{\mathrm{ext}}}_{k_\text{int}} Lact_\text{in} $$ Only the \(Lact_\text{in}\) state can react with the other chemical species in the doughnut and only \(Lact_\text{out}\) can react with other chemical species in the bulk. The value of \(k_\text{ext}\) was estimated based on [Dong, et al., 1993], while \(k_\text{int}\) was set to maintain a \(k_\text{ext}:k_\text{int}\) ratio of 20:1 [Dong, et al., 1993].

Since AHL can freely diffuse across membranes, unbound AHL is only modeled as one state that can diffuse across all barriers. The effective diffusion coefficient of lactate was estimated relative its coefficient in water \(D_{aq}\) by the relation $$\frac{D_e}{D_{aq}}\approx 0.25$$ using the approximation proposed in a 2003 review by Stewart. The diffusion coefficient of AHL through the membrane was computed from an AHL excretion rate of \(D_m = 100 \text{min}^{-1}\) [Kaplan, et al., 1985].

Correcting concentrations

Since E. coli are not fully packed into the domains in our model, a concentration correction has to be applied to the chemical species. If no correction is made for the strictly intracellular species, then the reported concentrations are single-cell. To compensate for the fact that AHL can diffuse across membranes, its production rate is scaled by the ratio of the total E. coli volume and the volume of the domain they are present in. Although this relation assumes instant diffusion of AHL, the small volume of the well makes this assumption approximately hold on our simulation timescale.

Implementing flow using boundary conditions

Since it is assumed that the presence of a constant flow of fluid on the top boundary of a well will draw away all of the free-floating molecules, this was implemented as a 0-concentration boundary condition on the top of the well.

Simulation in COMSOL Multiphysics

All simulations were run with 1000 time steps and a course mesh. For the full model, the course mesh led to convergence issues in the nonlinear solver, so a normal mesh was used.