Difference between revisions of "Team:Waterloo/Modeling/Cas9 Dynamics"

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

<h3>Model Validation</h3> | <h3>Model Validation</h3> | ||

<p>The model matched experimental results well and helped to shed light on the details of indels due to NHEJ. The clips bellow show three different examples of gene deactivation ranging from few cuts, many deactivations to high cuts, few deactivations.</p> | <p>The model matched experimental results well and helped to shed light on the details of indels due to NHEJ. The clips bellow show three different examples of gene deactivation ranging from few cuts, many deactivations to high cuts, few deactivations.</p> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="jumbotron hp-landing"> | <div class="jumbotron hp-landing"> | ||

<div class="container"> | <div class="container"> | ||

| Line 120: | Line 119: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

<div class="container"> | <div class="container"> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

<div class="container"> | <div class="container"> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 168: | Line 169: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | </div> | + | </div><br><br> |

<h3>Importance of Large Deletions</h3> | <h3>Importance of Large Deletions</h3> | ||

| Line 193: | Line 194: | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/18/Waterloo_Situation_1.png" height="50%" width="50%"><br> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/1/18/Waterloo_Situation_1.png" height="50%" width="50%"><br> | ||

| + | <p>1000 runs of target sum deactivation</p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/e/e4/Waterloo_Situation_2.png" height="50%" width="50%"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/e/e4/Waterloo_Situation_2.png" height="50%" width="50%"> | ||

| + | <p>1000 runs of single target deactivation</p> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| + | <p>Further developments we would like to pursue are adding proximity of targets to their large deletion probabilities and making the model simpler to apply to non-viral genomes.</p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:57, 19 September 2015

Modeling Genomic Effects of CRISPR/Cas9

CRISPR/Cas9 has been extensively studied for its applications in eukaryotic genome editing and gene expression control. Last year, the Waterloo iGEM team created an ODE model of dCas9 binding and control of gene expression. This year, however, the modelling team chose to investigate the effects of CRISPR/Cas9 on an genomic rather than molecular level. Specifically, we wanted to model the accumulation of mutations in a target genome and eventual deactivation of target genes after cutting by CRISPR/Cas9 and repair by Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ).

Model Formation

When bound to a single guide RNA (sgRNA), the S. pyogenes Cas9 nuclease diffuses through the cell in three dimensions, searching for the sequence 'NGG' in the target genome . When it finds an 'NGG', known as a PAM site, Cas9 binds and undergoes a conformational change that allows it to unwind the DNA helix and compare the sequence of its sgRNA with the DNA. If the sgRNA matches well, Cas9 cleaves the DNA, producing a double-stranded break (DSB) 3-4 bp upstream of the PAM site .

In the absence of a template, DSBs are repaired by Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), which is an error-prone process that sometimes creates indels at the site of repair . This effect has recently been exploited to target double-stranded viruses such as HBV . Though there have been extensive efforts to characterize the factors that contribute to effective targeting and deactivation by CRISPR/Cas9 and NHEJ, they have not, to the best of our knowledge, been synthesized into a single model.

The aim of the model is thus to capture the cutting events initiated by Cas9 and predict the outcomes of these events. We model each genome as containing multiple domains of interest, such as promoters or ORFs, and track whether these domains have been deactivated by CRISPR/Cas9 activity. There may be more than one sgRNA target in each domain and many domains can be targeted at once.

If Cas9 successfully cuts at a target site, the double-stranded break may be resolved in three ways. The most common resolution is for NHEJ to successfully repair the DSB without creating any indels

However, NHEJ repair is error-prone and will often induce indels at the target site. Finally, since multiple sgRNA targets are considered, it is possible that large deletions will occur between two targets that are simultaneously cut.

At each timestep, the model considered the state (cut or uncut) and sequence of all targets and computes the probability of the following events at each target: CRISPR/Cas9 cutting, NHEJ repair or large deletion. The remainder of the model formation section discusses how we determined the probability of each event.

Probability of Double-Stranded Cuts made by CRISPR/Cas9

The probability of a target being cut in a given time step was modelled as dependent on Cas9 concentration and sgRNA mismatches. The average time for a cut was also considered using the reported from 2-minute half-life Hemphill et al. .

Since Cas9 binds to PAM sites according to an approximately first order three dimensional diffusion we expect increasing concentration of Cas9 protein to lead to a higher probability of cutting. Concentration was incorporated into our model using a multiple regression on data from Kusku et al.(2014) , which related the proportion bound as a function of concentration and number of mismatches between the target and the sgRNA.

The effect of mismatches in the sgRNA (important for the residual targeting after indels have been introduced by NHEJ) was further considered using the relationship found by Hsu et al. . These effects were assumed to be independent, which likely overestimates mismatch effects and underestimated CRISPR/Cas9 efficacy.

Error-Prone Repair by Non-Homologous End Joining

Open breaks in the DNA were repaired according to an exponential decay, following the model of Reynolds et al. , which found that DSBs remained with a half-life of 8 minutes. Insertion and deletion sizes were chosen based on a distributions of indels observed by deep-sequencing of repaired targets (see data in ). When there is a net insertion, we selected from a uniform distribution of [ACGT] to add new nucleotides.

Large Deletions

The probability of large deletions was estimated using a study on large deletions, which measured the percentage of large deletions observed at 3 days and 10 days at several targets . We chose not to account for the effect of the distance between targets for large deletions, though it could be incorporated in future studies .

No Interaction Between Genomes

We expect there to be multiple viral genomes in our plant defense example and it is possible that simultaneous cuts on different genomes could result two genomes being joined together. However, we chose to disregard this possibility and averaged results from multiple stochastic simulations could be averaged to get an overall picture of gene deactivation by Cas9.

Software Implementation

Genome Classes

The code uses three classes to model the genome. Genomes have domains which have targets. Targets handle probabilities, domains track functionality and genome modifies everything.

class Target():

is associated with a domain

class Domain():

has targets

is associated with a genome

class Genome():

has domains

Genome Simulation

The simulation calls these classes to check if events have occurred and the details of each event. At the end it compiles the data logs into CSVs, plots and visualizations.

for dt in time_steps:

call genome_classes to check if there was a cut, repair or large deletion

if event:

add to log

generate CSVs, plots and visualizations

To see all the code for the simulation, check out our GitHub Page

Results

Model Validation

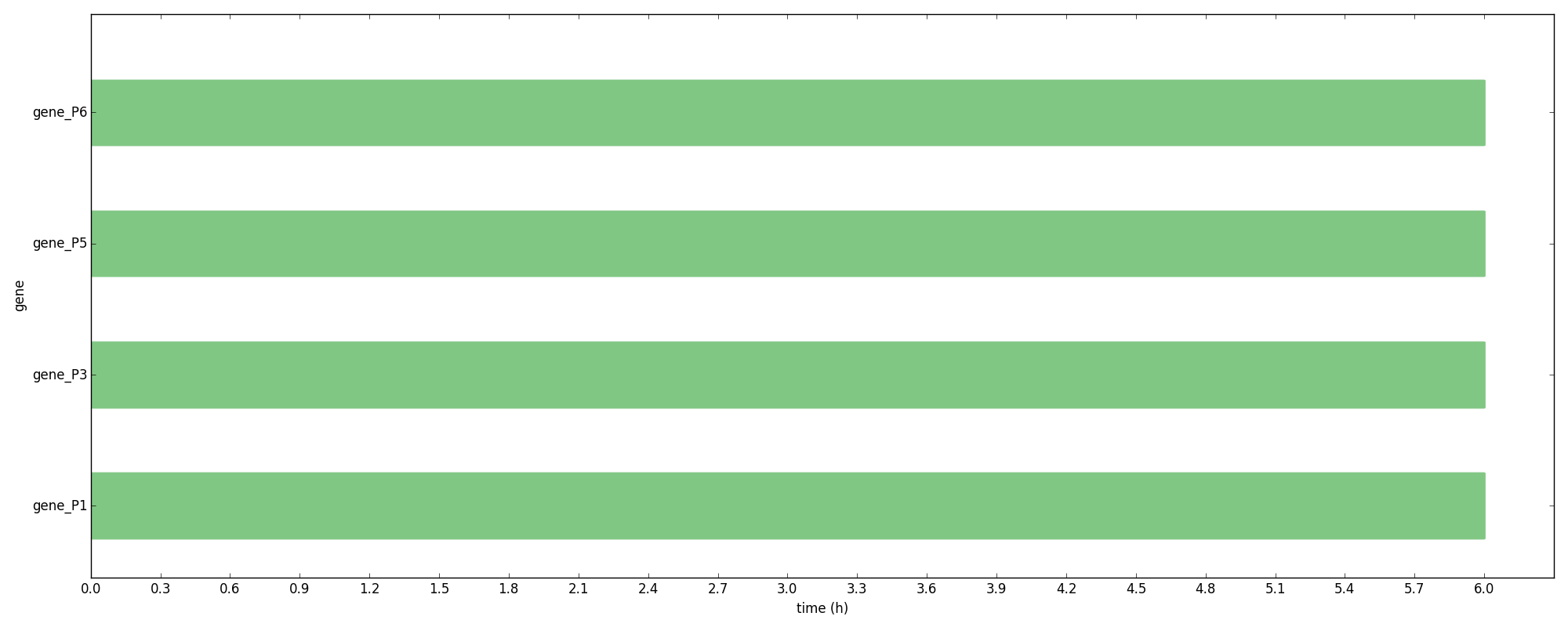

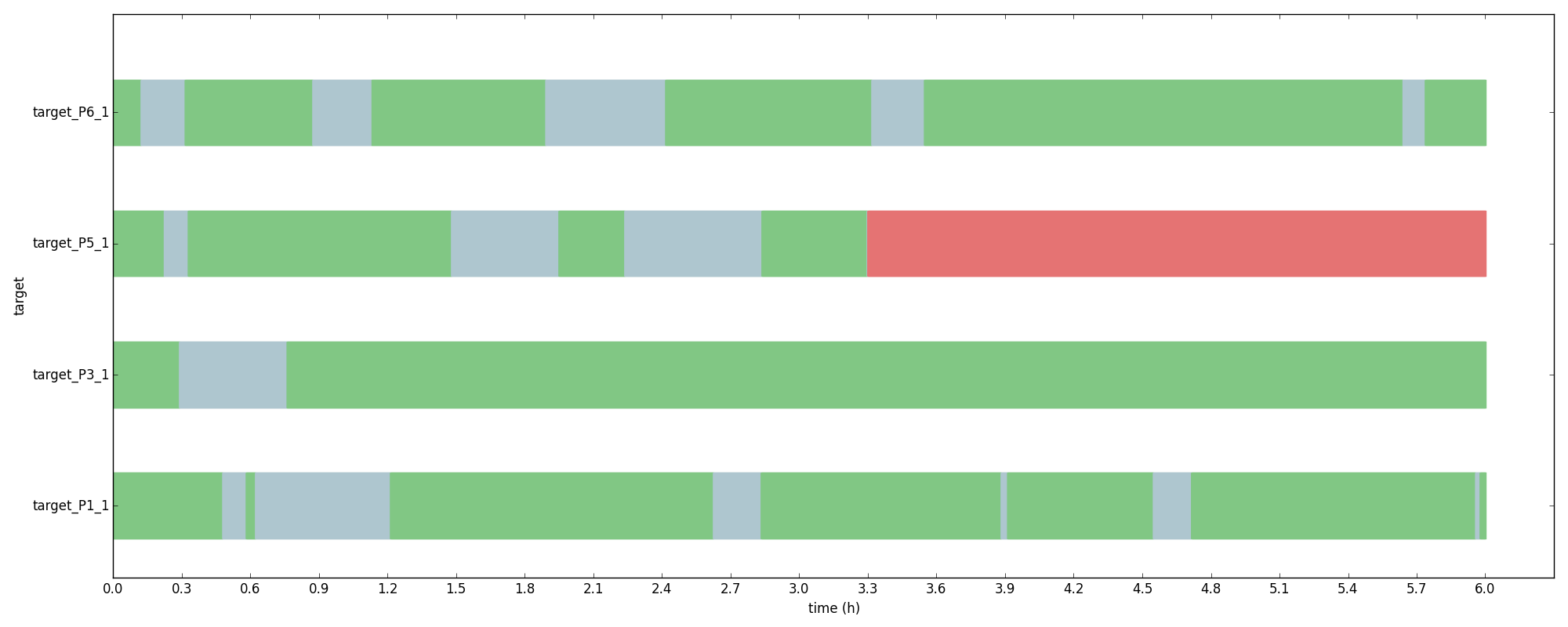

The model matched experimental results well and helped to shed light on the details of indels due to NHEJ. The clips bellow show three different examples of gene deactivation ranging from few cuts, many deactivations to high cuts, few deactivations.

Importance of Large Deletions

Our interest in modeling large deletions was to investigate whether they would be a viable method for deactivating viral targets. The infrequency of large deletions according to experimental results and inputed in our model showed that they are not a reliable method of deactivating genes.

Effect of Cas9 Concentration

Through experimentation with the model we found that varying the Cas9 concentration had a surprisingly small efect on the strength of the system. This is likely because the standard concentration is already nearly saturated and increasing this value does not significantly increase binding.

Predicting CRISPR Plant Defense

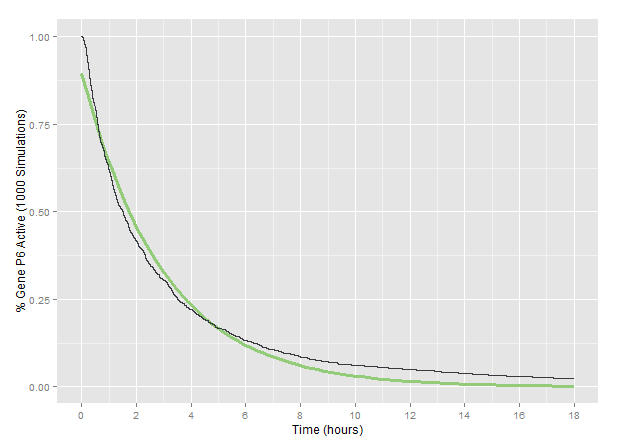

This model was applied to the CRISPR Plant Defense aspect of our project, investigating whether the P6 protein of Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) could be deactivated by frameshift mutations. The P6 protein was chosen as a focus of the investigation because it suppresses natural plant RNAi defenses and trans-activates translation of other CaMV proteins . Details on P6 and the CaMV genome can be found on CaMV Biology page.

The model was run with three targets in the P6 gene of the simulated CaMV genome described. The particular sgRNA target locations in P6 are those described as Design II on the related wet lab page. We tracked the percent of simulated genomes with functional P6 across 1000 runs fo the model, giving a general prediction of how long it will take before the P6 of a particular CaMV genome is rendered non-functional by our Plant Defense system.

Based on the fit to our 1000-simulation average, we considered our CRISPR Plant Defense system to render the P6 gene of CaMV non-functional according to an exponential decay with a decay constant of 6.36x10

Future Research

An interesting pattern we noticed when determining how to measure gene activation was that recording the sum of the target shifts as opposed to the individual shifts lead to reactivation after a few hours. This is likely due to some active targets being re-shifted and actually fixing the gene. The first figure shows gene activation measured by the sum of target shifts and the second figure shows gene activation measured by individual shifts (where any non multiple 3 shift causes deactivation.)

1000 runs of target sum deactivation

1000 runs of single target deactivation

Further developments we would like to pursue are adding proximity of targets to their large deletion probabilities and making the model simpler to apply to non-viral genomes.