Difference between revisions of "Team:Waterloo/Description"

m (previous content in highlightbox) |

(adds lots of new graphics) |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Waterloo}} | {{Waterloo}} | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| − | <div | + | <div class="container main-container"> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <h1> | + | <h1>Project Description</h1> |

| − | <section id="motivation"> | + | <section id="motivation" title="Motivation"> |

<h2>Motivation</h2> | <h2>Motivation</h2> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | The CRISPR-Cas9 system is an | + | The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system is an exciting tool for synthetic biologists because it can target and edit genomes with unprecedented specificity. The <span class="orangetext">Cas9 Protein</span> binds to a PAM site (NGG), attempts to match its <span class="bluetext">sgRNA target sequence</span> to the adjacent DNA strand and cleaves the DNA if it finds a match. Since its popularization, CRISPR papers have flooded major journals and many iGEM teams have worked to improve its use as a genome editing tool.</p> |

| + | <p>The 2015 Waterloo team is taking a three-pronged approach to expand upon previous research for wider, more efficient, and more flexible use of CRISPR-Cas9: easy testing of sgRNA designs with our <span class="bluetext">Simple sgRNA Exchange</span> design, applying research on new mutations in Cas9's PAM-interacting domain to enable <span class="orangetext">Cas9 PAM Flexibility</span> and applying our work as a <span class="greentext">CRISPR Plant Defense</span> protecting <em>A. thaliana</em> against infection by Cauliflower Mosaic Virus. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/1/1a/Waterloo_project-overview.png" alt="CRISPR-Cas9 structure and project overview" /> | ||

| + | <figcaption>Overview of CRISPR-Cas9 structure and project sections</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </section> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <section id="sgRNA" title="sgRNA Modification" class="sgRNAmod"> | ||

| + | <h2>Simple sgRNA Exchange</h2> | ||

| + | <figure style="float:left; max-width:30%; width:150px;"> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/8/85/Waterloo_sgrnaexchangeicon.png" alt="sgRNA Exchange Icon" /> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | We aim to make target selection and guide sequence replacement physically easier in the lab. To target a DNA sequence, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) is used to identify a match. | + | We aim to make target selection and guide sequence replacement physically easier in the lab. To target a DNA sequence, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) is used to identify a match <cite ref="Horvath2010"></cite>. We modify the sgRNA secondary structure analyzed by Briner et al. <cite ref="Briner2014"></cite> to contain a restriction site. This makes it possible to swap out a 20 base pair section of the sgRNA sequences, instead of synthesizing new targets from scratch, so there is no need to re-synthesize and re-clone the entire sgRNA sequence for each new target we'd like to test. We hope our design reduces the turnaround time for using CRISPR to target different sequences. |

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | < | + | <figure> |

| − | + | <img src="/wiki/images/7/78/Waterloo_sgrna_scaffold.png" alt="sgRNA scaffold structure" style="width:50%;" /> | |

| − | </ | + | <figcaption>sgRNA scaffold structure</figcaption> |

| − | <p> | + | <div class="img-att">i |

| − | + | <ul class="img-att-bubble"> | |

| + | <li>Briner et al., 2014 <cite ref="Briner2014"></cite></li> | ||

| + | <li>Cropped image</li> | ||

| + | <li><a href="http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MiamiCaptionURL&_method=retrieve&_eid=1-s2.0-S1097276514007515&_image=1-s2.0-S1097276514007515-gr1.jpg&_cid=272198&_explode=defaultEXP_LIST&_idxType=defaultREF_WORK_INDEX_TYPE&_alpha=defaultALPHA&_ba=&_rdoc=1&_fmt=FULL&_issn=10972765&_pii=S1097276514007515&md5=2b34d1b5899d9fa9a88dc9bf04fb8b64">Link to Original Photo</a></li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | <p class="desc-links" style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Lab/sgRNA">Background and Results</a> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

| − | <section id=" | + | <section id="cas9" title="Cas9 PAM Flexibility" class="cas9mod"> |

| − | <h2> | + | <h2>Cas9 PAM Flexibility</h2> |

| + | <figure style="float:left; max-width:30%; width:150px;"> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/7/72/Waterloo_pamflexeicon.png" alt="Pam Exchange Icon" /> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | By building on recent papers, such as <cite ref="Kleinstiver2015"></cite>, we are trying to make Cas9’s binding to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site more flexible. The standard <i>S. pyogenes</i> type II CRISPR-Cas9 binds to a PAM of length 3, namely NGG <cite ref="Kleinstiver2015"></cite>. While this is fairly general, requiring that this sequence be next to the target sequence limits where Cas9 can cut. We have produced a model that suggests Cas9 variants and their preferred PAM sites, and we attempted to demonstrate this model’s validity. The overarching goal is to create Cas9 variants that will bind to any desired PAM site, and we hope to take some significant steps forward to make that goal more achievable and directed. | |

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p class="desc-links" style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Lab/dCas9">Lab Design</a> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/PAM_Flexibility">Modeling</a> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Practices/Human_Practices">IP Laws</a> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

| − | <section id=" | + | <section id="plants" title="CRISPR Plant Defense" class="plantmod"> |

| − | <h2> | + | <h2>CRISPR Plant Defense</h2> |

| + | <figure style="float:left; max-width:30%; width:150px;"> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/7/73/Waterloo_plantdefenseicon.png" alt="Plant Defense Icon" /> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | Finally, CRISPR originated as a viral defence mechanism for bacteria, for specific and targeted immunity <cite ref="Horvath2010"></cite>. Multi-cellular organisms have developed their own defenses to achieve this goal, but from our research it appears that groups have not publicly attempted to introduce CRISPR as an antiviral mechanism in multicellular organisms. Our team is attempting to use the CRISPR system in plants to discover whether it can defend against a class of double-stranded DNA viruses. | |

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p class="desc-links" style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/CaMV_Biology">CaMV Background</a> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Lab/Plants">Lab Design</a> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/CaMV_Replication">Modeling CaMV Replication</a> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Modeling/Intercellular_Spread">Modeling Intercellular Spread</a> | ||

| + | <a href="/Team:Waterloo/Practices/Commercialization">Commercialization</a> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

| − | <section id=" | + | <section id="references" title="References"> |

| − | <h2> | + | <h2>References</h2> |

| − | < | + | <ol id="reflist"> |

| − | + | </ol> | |

| − | </ | + | |

</section> | </section> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

{{Waterloo_Footer}} | {{Waterloo_Footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:01, 20 November 2015

Project Description

Motivation

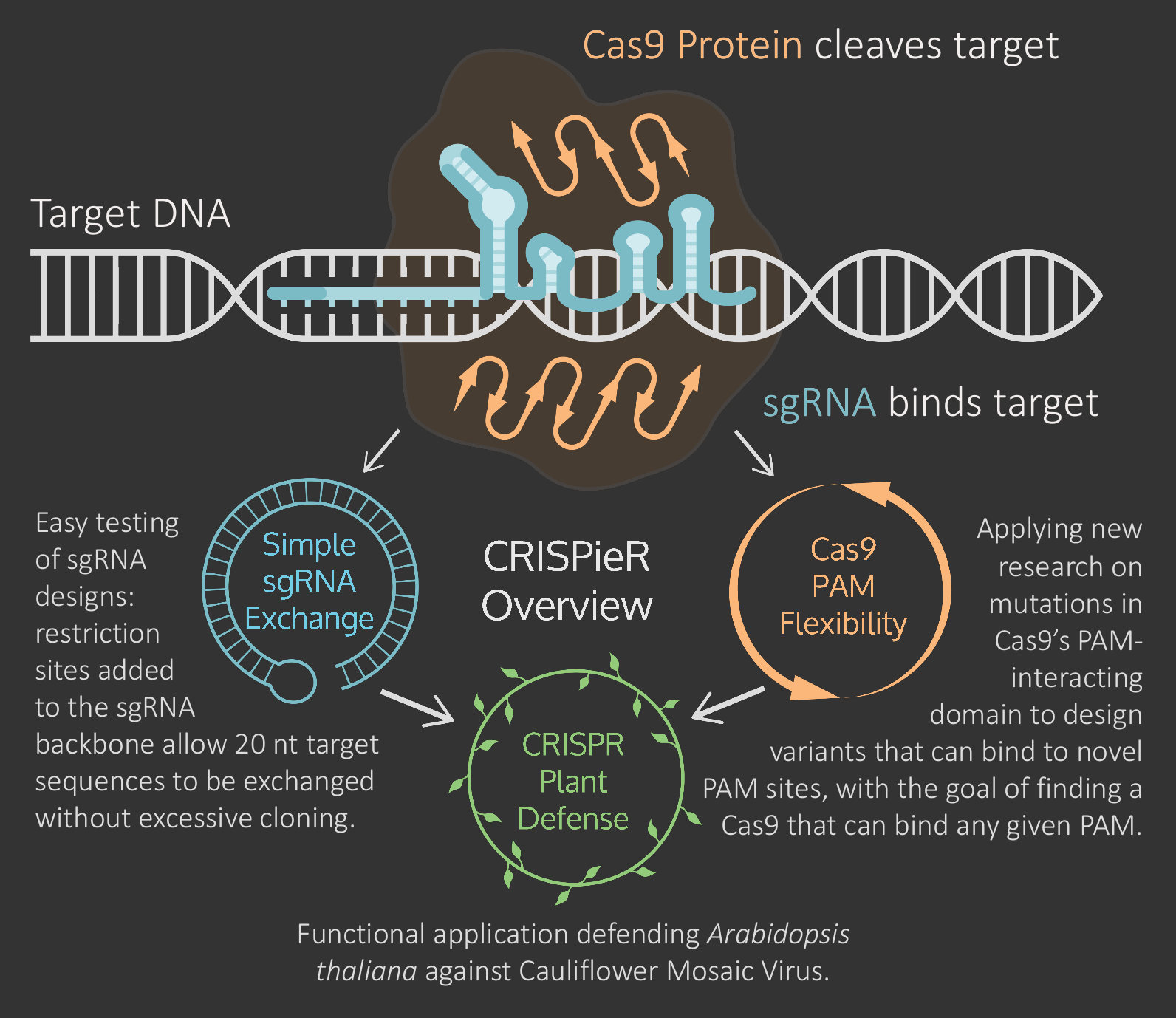

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system is an exciting tool for synthetic biologists because it can target and edit genomes with unprecedented specificity. The Cas9 Protein binds to a PAM site (NGG), attempts to match its sgRNA target sequence to the adjacent DNA strand and cleaves the DNA if it finds a match. Since its popularization, CRISPR papers have flooded major journals and many iGEM teams have worked to improve its use as a genome editing tool.

The 2015 Waterloo team is taking a three-pronged approach to expand upon previous research for wider, more efficient, and more flexible use of CRISPR-Cas9: easy testing of sgRNA designs with our Simple sgRNA Exchange design, applying research on new mutations in Cas9's PAM-interacting domain to enable Cas9 PAM Flexibility and applying our work as a CRISPR Plant Defense protecting A. thaliana against infection by Cauliflower Mosaic Virus.

Simple sgRNA Exchange

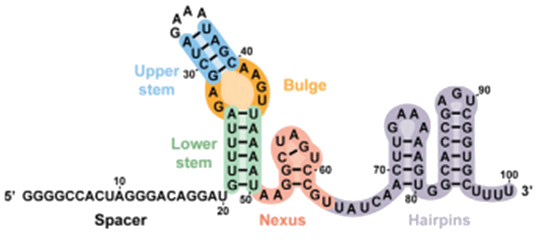

We aim to make target selection and guide sequence replacement physically easier in the lab. To target a DNA sequence, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) is used to identify a match . We modify the sgRNA secondary structure analyzed by Briner et al. to contain a restriction site. This makes it possible to swap out a 20 base pair section of the sgRNA sequences, instead of synthesizing new targets from scratch, so there is no need to re-synthesize and re-clone the entire sgRNA sequence for each new target we'd like to test. We hope our design reduces the turnaround time for using CRISPR to target different sequences.

- Briner et al., 2014

- Cropped image

- Link to Original Photo

Cas9 PAM Flexibility

By building on recent papers, such as , we are trying to make Cas9’s binding to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site more flexible. The standard S. pyogenes type II CRISPR-Cas9 binds to a PAM of length 3, namely NGG . While this is fairly general, requiring that this sequence be next to the target sequence limits where Cas9 can cut. We have produced a model that suggests Cas9 variants and their preferred PAM sites, and we attempted to demonstrate this model’s validity. The overarching goal is to create Cas9 variants that will bind to any desired PAM site, and we hope to take some significant steps forward to make that goal more achievable and directed.

CRISPR Plant Defense

Finally, CRISPR originated as a viral defence mechanism for bacteria, for specific and targeted immunity . Multi-cellular organisms have developed their own defenses to achieve this goal, but from our research it appears that groups have not publicly attempted to introduce CRISPR as an antiviral mechanism in multicellular organisms. Our team is attempting to use the CRISPR system in plants to discover whether it can defend against a class of double-stranded DNA viruses.

CaMV Background Lab Design Modeling CaMV Replication Modeling Intercellular Spread Commercialization