Difference between revisions of "Team:Waterloo/Design"

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

<section id="sgRNA" title="sgRNA Modification" class="sgRNAmod"> | <section id="sgRNA" title="sgRNA Modification" class="sgRNAmod"> | ||

<h2>Simple sgRNA Exchange</h2> | <h2>Simple sgRNA Exchange</h2> | ||

| − | < | + | <figure style="float:left; max-width:30%; width:150px;"> |

| − | + | <img src="/wiki/images/8/85/Waterloo_sgrnaexchangeicon.png" alt="sgRNA Exchange Icon" /> | |

| − | </p> | + | </figure> |

| − | <p> | + | |

| − | + | <p>The ability re-purpose sgRNAs to guide Cas9 to new target sites currently requires re-cloning the entire 500 base pair sgRNA sequence. The turnaround time needed to test different sgRNA sequences is a problem because different sgRNA are known to have very different biochemical activity <cite ref="Doench2014"></cite>, in some studies ranging from 9%-60% cleavage efficiency, and these efficiencies cannot always be predicted computationally <cite ref="Wang2015"></cite>.</p> | |

| − | </p> | + | |

| − | + | <figure> | |

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/5/5b/Waterloo_doenchfig3.jpg" alt="Doench et al Figure 3 part A; sgRNA efficiency" /> | ||

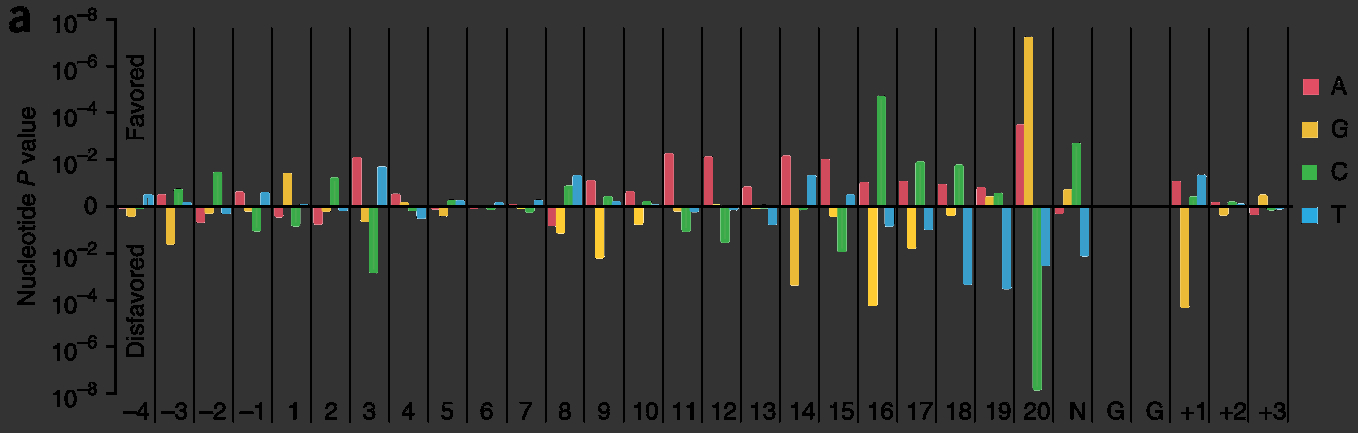

| + | <figcaption>Biochemical determinants in sgRNA activity: certain nucleotides tend to occupy specific positions in highly-active sgRNA. This shows "p-values of observing the conditional probability of a guide with a percent-rank activity of >0.8 under the null distribution" <cite ref="Doench2014"></cite>.</figcaption> | ||

| + | <div class="img-att">i | ||

| + | <ul class="img-att-bubble"> | ||

| + | <li>Briner et al., 2014 <cite ref="Doench2014"></cite></li> | ||

| + | <li>Adapted from Figure 3</li> | ||

| + | <li><a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4262738/">Link to Original Photo</a></li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>By inserting restriction enzyme sites flanking the 20 base pair guide sequence of sgRNA, researchers will have the ability to more easily swap in new targets for Cas9. By taking advantage of the existence of a single "G" nucleotide at the bottom of the first stem-loop that doesn't follow complementarity with the opposing nucleotide in the sgRNA scaffold, we were able to insert a restriction enzyme site without also introducing that site downstream in the original DNA sequence. We then placed another restriction site after the U6 promoter but before the gRNA to complete the swap. Our experiments showed that this modified version of the sgRNA was still capable of working to silence gene expression with a dCas9 in similar level as the non-modified. You can read about the design in detail on the <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Lab/sgRNA">Simple sgRNA Exchange Page</a>.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/7/71/Waterloo_sgrna_original.png" alt="modified sgRNA scaffold structure"/> | ||

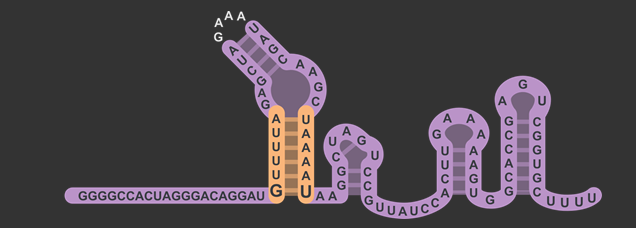

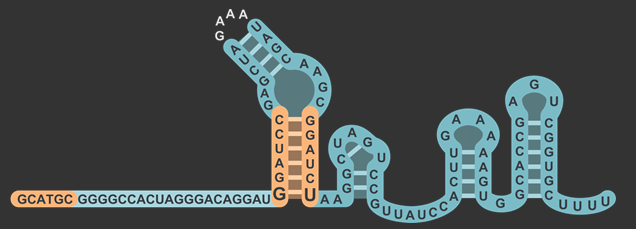

| + | <figcaption>sgRNA scaffold structure, different modules identified by Briner et al. <cite ref="Briner2014"></cite>.</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/2/29/Waterloo_sgrna_mod.png" alt="modified sgRNA scaffold structure"/> | ||

| + | <figcaption>Modified sgRNA structure, including restriction site in the lower stem and before the 20nt gRNA sequence.</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

<section id="cas9" title="Cas9 PAM Flexibility" class="cas9mod"> | <section id="cas9" title="Cas9 PAM Flexibility" class="cas9mod"> | ||

<h2>Cas9 PAM Flexibility</h2> | <h2>Cas9 PAM Flexibility</h2> | ||

| + | <figure style="float:left; max-width:30%; width:150px;"> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/7/72/Waterloo_pamflexeicon.png" alt="Pam Exchange Icon" /> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | Being able to target DNA at different protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site will allow scientists to target a larger portion of the genome. "Dead" Cas9 (dCas9) allows for easier analysis of products because the DNA still remains intact. Kleinstiver et al proposed an EQR variant of Cas9 with three amino acid substitutions. This new proposed version of Cas9 targeted an NGAG PAM sequence. Our design was to make these three amino acid substitutions in dCas9 and try to target an NGAG PAM site in GFP. | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | <p>Kleinstiver et al. recently demonstrated modified spCas9 with altered PAM specificity <cite ref="Kleinstiver2015"></cite>. | |

| + | Their results motivated us to explore computational methods of assessing spCas9 mutants for altered PAM specificity profiles. We created an analysis pipeline using python that makes use of PyRosetta, a well known molecular dynamics toolkit. Our suite of scripts is described in our <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling">Modeling</a> and <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Software">Software</a> pages. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

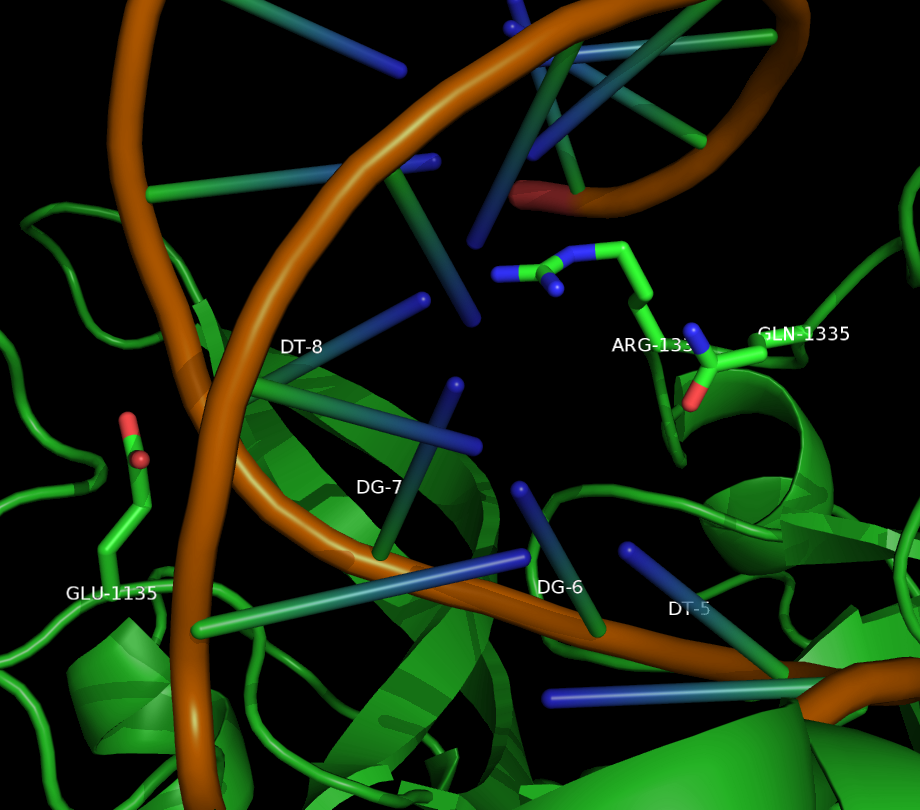

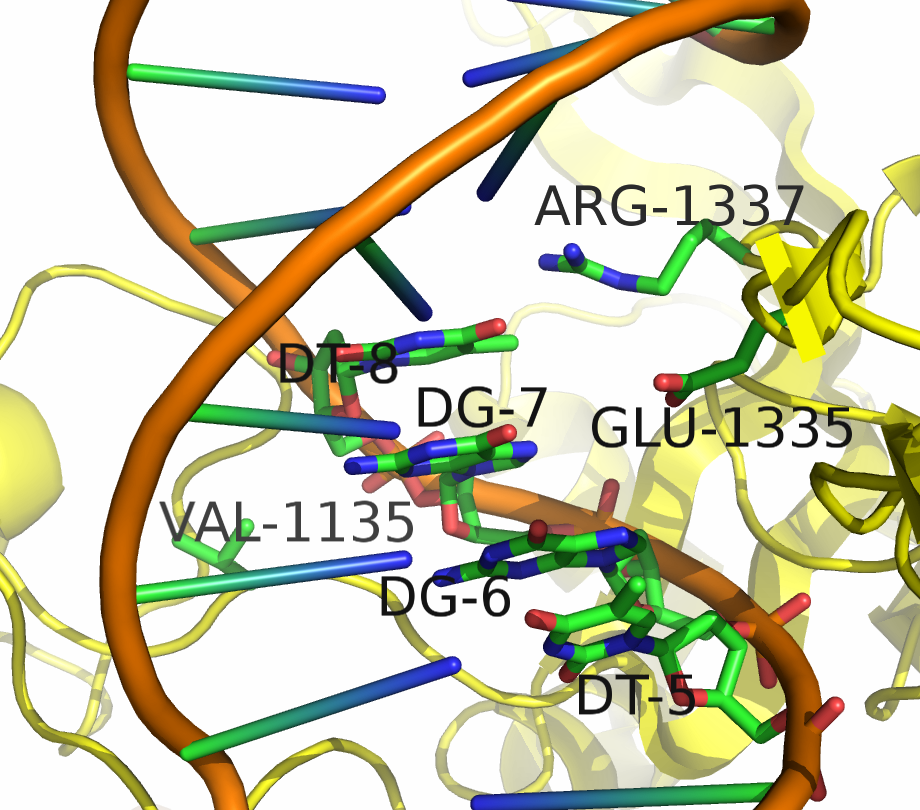

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/d/da/Waterloo_wt_residues.png" alt="Wild Type spCas residues" class="img-responsive"> | ||

| + | <figcaption>A PyMOL generated image of the wild type residues near the PAM binding site of spCas9.</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/8/8c/Eqr_mutated_residues.png" alt="EQR Mutated Residues" class="img-responsive"> | ||

| + | <figcaption>A PyMOL generated image of the three mutations found in the EQR spCas9 variant</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/0/0d/Waterloo_VQR_mutated_residues.png" alt="VQR Mutated Residues" class="img-responsive"> | ||

| + | <figcaption>A PyMOL generated image of the three mutations found in the VQR spCas9 variant</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

| − | <section id="plants" title="CRISPR Plant | + | <section id="plants" title="CRISPR Plant Defense" class="plantmod"> |

| − | <h2>CRISPR Plant | + | <h2>CRISPR Plant Defense</h2> |

| + | <figure style="float:left; max-width:30%; width:150px;"> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/7/73/Waterloo_plantdefenseicon.png" alt="Plant Defense Icon" /> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | By integrating an expression cassette that included Cas9 and three sgRNAs that target the CaMV genome in an important coding sequence into the shuttle vector pCAMBIA, we'll be able to integrate that cassette into the <i> Arabidopsis</i> genome using nature's genetic engineer, <i>Agrobacterium</i>. | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | </section> | ||

| + | <p> To model our antiviral application, we looked at the antiviral effects of CRISPR/Cas9 targeting on three scales: CaMV genomes, plant cells and plant leaves. Details of our modeling approach, and how it influenced our design, are provided in our <a href="https://2015.igem.org/Team:Waterloo/Modeling">Modeling</a> pages.</p> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/5/5f/Waterloo_mathCAS_graphic.svg" class="img-responsive" alt="Stylized viral genome" style="width:200px;"/> | ||

| + | <figcaption class="model-caption">CaMV Genomes</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/9/98/Waterloo_mathVA_graphic.svg" class="img-responsive" alt="Stylized plant cell" style="width:200px;"/> | ||

| + | <figcaption class="model-caption">Plant Cells</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-sm-4"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/d/da/Waterloo_mathVS_graphic.svg" class="img-responsive" alt="Stylized plant leaves" style="width:200px;"/> | ||

| + | <figcaption class="model-caption">Plant Leaves</figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

</p> | </p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

| Line 40: | Line 113: | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

{{Waterloo_Footer}} | {{Waterloo_Footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:07, 20 November 2015

Design

Simple sgRNA Exchange

The ability re-purpose sgRNAs to guide Cas9 to new target sites currently requires re-cloning the entire 500 base pair sgRNA sequence. The turnaround time needed to test different sgRNA sequences is a problem because different sgRNA are known to have very different biochemical activity , in some studies ranging from 9%-60% cleavage efficiency, and these efficiencies cannot always be predicted computationally .

- Briner et al., 2014

- Adapted from Figure 3

- Link to Original Photo

By inserting restriction enzyme sites flanking the 20 base pair guide sequence of sgRNA, researchers will have the ability to more easily swap in new targets for Cas9. By taking advantage of the existence of a single "G" nucleotide at the bottom of the first stem-loop that doesn't follow complementarity with the opposing nucleotide in the sgRNA scaffold, we were able to insert a restriction enzyme site without also introducing that site downstream in the original DNA sequence. We then placed another restriction site after the U6 promoter but before the gRNA to complete the swap. Our experiments showed that this modified version of the sgRNA was still capable of working to silence gene expression with a dCas9 in similar level as the non-modified. You can read about the design in detail on the Simple sgRNA Exchange Page.

Cas9 PAM Flexibility

Being able to target DNA at different protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site will allow scientists to target a larger portion of the genome. "Dead" Cas9 (dCas9) allows for easier analysis of products because the DNA still remains intact. Kleinstiver et al proposed an EQR variant of Cas9 with three amino acid substitutions. This new proposed version of Cas9 targeted an NGAG PAM sequence. Our design was to make these three amino acid substitutions in dCas9 and try to target an NGAG PAM site in GFP.

Kleinstiver et al. recently demonstrated modified spCas9 with altered PAM specificity . Their results motivated us to explore computational methods of assessing spCas9 mutants for altered PAM specificity profiles. We created an analysis pipeline using python that makes use of PyRosetta, a well known molecular dynamics toolkit. Our suite of scripts is described in our Modeling and Software pages.

CRISPR Plant Defense

By integrating an expression cassette that included Cas9 and three sgRNAs that target the CaMV genome in an important coding sequence into the shuttle vector pCAMBIA, we'll be able to integrate that cassette into the Arabidopsis genome using nature's genetic engineer, Agrobacterium.

To model our antiviral application, we looked at the antiviral effects of CRISPR/Cas9 targeting on three scales: CaMV genomes, plant cells and plant leaves. Details of our modeling approach, and how it influenced our design, are provided in our Modeling pages.