Difference between revisions of "Team:Nagahama/Description"

(→Why Flavorator?) |

(→Overview of our design) |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

| − | (1) First, in ''E. coli'' | + | (1) First, in ''E. coli'' terpenes's precursors, such as isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), are produced by non-mevalonate (MEP) pathway. In MEP pathway, there are four enzymes, (''ispD'', ''ispF'', ''idi'', and ''dxs'') that are rate-limiting enzymes to produce terpenes’s precursors in ''E. coil''. In order to create a high-yield strains producing IPP and DMAPP, we exogenously engineer to superimpose these genes into ''E. coli'' to create strains overproducing IPP and DMAPP in a MEP pathway. |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

(2) Second, in addition to introduction of three genes in a MEP pathway, we further introduced farnecil diphosphate synthase gene (''ispA'') or its mutant (''m-ispA'', S80F) from ''E. coli'' in combination with geraniol synthase gene from ''Ocimum basilicum'' (''ObGES''). These gene-combinations are possible to convert IPP and DMAPP into to farnesol or geraniol, respectively. | (2) Second, in addition to introduction of three genes in a MEP pathway, we further introduced farnecil diphosphate synthase gene (''ispA'') or its mutant (''m-ispA'', S80F) from ''E. coli'' in combination with geraniol synthase gene from ''Ocimum basilicum'' (''ObGES''). These gene-combinations are possible to convert IPP and DMAPP into to farnesol or geraniol, respectively. | ||

Revision as of 02:05, 18 September 2015

Contents

Introduction

Why Flavorator?

Food problems is are a serious matter in the world. Among them, food preservation is the one. Ideal food preservation is keeping food without causing quality change for longer time with cost effectively. A plenty of preservation methods have been used so far, we created a new one to solve it. It is "Flavorator"!!

Thirty years ago, “KOZOKO(香蔵庫 in Japanese)” was proposed by Professor Yozo Iwanami. The name “KOZOKO” can be directly translated into ‘flavor (=KO, 香)’- ‘preserved (=ZO, 蔵)’- ‘box (=KO, box)’. However, “KOZOKO” is not just a flavor-keeping reservoir, but a preservation box to preserve food in a fragrance. Then, what flavors we fill in KOZOKO? Such flavors should have antimicrobial; and/or insecticidal activities. The best candidates are plant’s origin. Plants cannot move to other places, if microbes and/or insects attack them. So, they produce antimicrobial and/or insecticidal agents, mostly they are not harmful to human and animals. In combination with the antimicrobial flavors, “KOZOKO” would become an energy-saving substitute for an ordinary electric refrigerator. Before doing so, it has two problems to be realized. The one is that We must select appropriate flavors and/or plants that can be cultivated under the various climate. The another is that cost issues must be cleared, as mass cultivation of the plant and extraction of pure flavors from plants is expensive and requires time-consuming process. As a result, “KOZOKO” is under the state of conceptual idea.

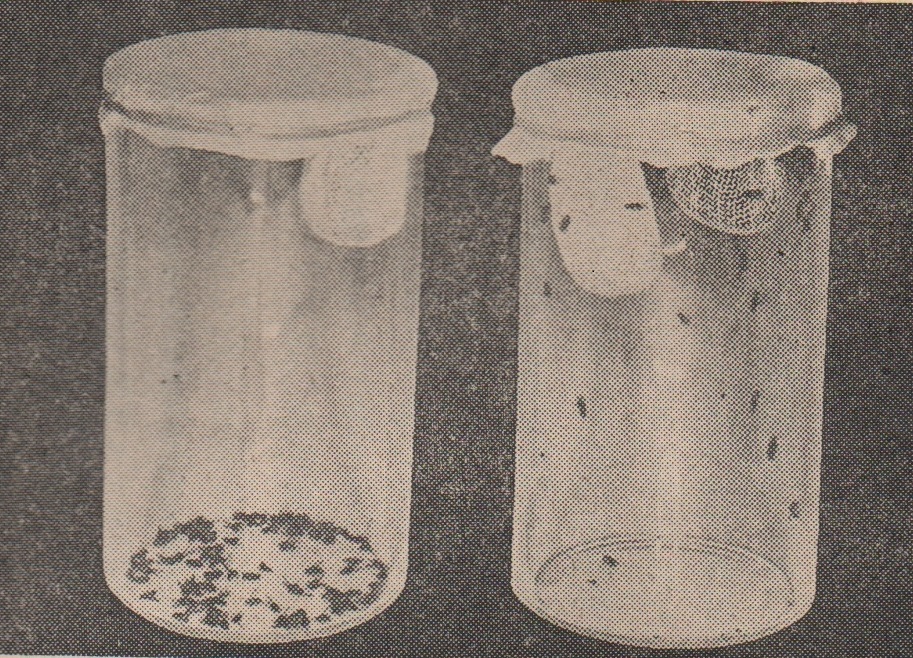

Here, we create a new version of “KOZOKO” utilizing syntheticbiology. And we want to solve Food problem all of the world! We named it “Flavorator”. Recombinant E. coli produces antimicrobial and insecticidal volatile gaseous substances that suppress bacterial unwanted growth in the “Flavorator” and prevent the insects from entering the “Flavorator”. Our choice was geraniol and farnesol. The reason for our choice is that they are terpenes and can be produced in E. coli easily after engineering its metabolic pathways. And they have high antimicrobial activity. Geraniol and farnesol are the major constituents of rose fragrance. These fragrances not only harmlessly emit fragrant odor to humans but also kill/or suppress microbes as well as insects like fruit flies.

We designed our strategy following three sequential steps in order to realize “Flavorator”.

Step 1: increase in the amount of terpene's precursors.

Step 2: Production of geraniol and/or farnesol.

Step 3: Efficient export of geraniol and/or farnesol to the media.

Following these three steps, we are sure that we will achieve realization of concept of “Flavorator” that can avoid food decay and solve one of the food problems in the future.

Overview of our design

DXP: 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate. MEP: 2-C-methylerythritol 4-phosphate. CDP-ME: 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol. CDP-MEP: 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2-phosphate. MEC: 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2, 4-cyclodiphosphate. HMBPP: (E)-4-Hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate. IPP: Isopentenyl pyrophosphate. DMAPP: Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate. GPP: geranyl diphosphate. FPP: farnesyl diphosphate.

(1) First, in E. coli terpenes's precursors, such as isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), are produced by non-mevalonate (MEP) pathway. In MEP pathway, there are four enzymes, (ispD, ispF, idi, and dxs) that are rate-limiting enzymes to produce terpenes’s precursors in E. coil. In order to create a high-yield strains producing IPP and DMAPP, we exogenously engineer to superimpose these genes into E. coli to create strains overproducing IPP and DMAPP in a MEP pathway.

(2) Second, in addition to introduction of three genes in a MEP pathway, we further introduced farnecil diphosphate synthase gene (ispA) or its mutant (m-ispA, S80F) from E. coli in combination with geraniol synthase gene from Ocimum basilicum (ObGES). These gene-combinations are possible to convert IPP and DMAPP into to farnesol or geraniol, respectively.

(3) Finally, we further introduce an activator gene of AcrAB-TolC efflux pump (MarA) to release the farnesol and geraniol from the cells and increase the content in the media that shows increase these flavors in the air.

Plasmid Construction

The ispA encodes Farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Farnesyl diphosphate synthase can utilize both dimethylallyl and geranyl diphosphates as substrates, generating geranyl and farnesyl diphosphate, respectively. Therefore the enzyme can catalyze two sequential reactions in the polyisoprenoid biosynthetic pathway. In E. coli, farnesyl diphasphate is dephosphorylate by enzyme of its own. As a result, this device can synthesis farnesol.

The m-ispA (geranyl diphosphate synthase gene) is mutant of ispA mutated S80F Geranyl diphosphate synthase can utilize dimethylallyl as substrates, generating geranyl diphosphate. and ObGES encodes geraniol synthase. Geraniol synthase dephosphorylate geranyl diphosphate. As a result, this device can synthesis geraniol.

Reference

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Journal+of+Biotechnology+169%2C+42%E2%80%93+50 [1]] Jia Zhou. et al, 2014 "Engineering Escherichia coli for selective geraniol production with minimized endogenous dehydrogenation" Journal of Biotechnology 169, 42– 50

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Biosci.+Biotechnol.+Biochem+73%2C+186-188 [2]] Chikara OHTO. et al, 2009 "Prenyl Alchol Production by Expression of Exogenenous Isopentenyl Diphosphate Isomerase and Farnesyl Diphosphate Synthase Genes in Escherichia coli" Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem 73, 186-188

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Journal+of+Biotechnology+167%2C+357-364 [3]] Asad Ali Shah. et al, 2013 "RecA-mediated SOS response provides a geraniol tolerance in Escherichia coli" Journal of Biotechnology 167, 357-364

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=NATURE+509%2C+512-515 [4]] Dijun Du. et al, 2014 "Structure of the AcrAB–TolC multidrug efflux pump" NATURE 509, 512-515

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Journal+of+Bioscience+and+Bioengineering+115(3)+%2C+253-258 [5]] Asad Ali Shah, et al, 2013 "Enhancement of geraniol resistance of Escherichia coli by MarA overexpression" Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 115(3) , 253-258

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Metabolic+Engineering+17%2C+42-50 [6]] Jing Zhao, et al, 2013 "Engineering central metabolic modules of Escherichia coli for improving β-carotene production" Metabolic Engineering 17, 42-50

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Biotechnology+and+Bioengineering+107(3)%2C+421-429 [7]] Chonglong Wang, et al, 2010 "Farnesol Production From Escherichia coli by Harnessing the Exogenous Mevalonate Pathway" Biotechnology and Bioengineering 107(3), 421-429

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Science+349%2C+81-83 [8]] Jean-Louis Magnard, et al, 2015 "Biosynthesis of monoterpene compounds in roses scent" Science 349, 81-83

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Plant+Physiol+134%2C+370-379 [9]] Yoko Iijima, et al, 2004 "Characterization of Geraniol Synthase from the Peltate Glands of Sweet Basil" Plant Physiol 134, 370-379

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16257556 [10]] Luke Z. Yuan, et al, 2006 "Chromosomal promoter replacement of the isoprenoid pathway for enhancing carotenoid production in E. coli" Metabolic Engineering 8, 79–90

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Journal+of+Biotechnology+140%2C+218%E2%80%93226 [11]]Sang-Hwal Yoon, et al, 2009 "Combinatorial expression of bacterial whole mevalonate pathway for the production of β-carotene in E. coli" Journal of Biotechnology 140, 218–226

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Anal+Biochem+421(1)%2C+158%E2%80%93163 [12]] Jonathan K Dozier, et al, 2012 "An enzyme-coupled continuous fluorescence assay for farnesyl diphosphate synthases" Anal Biochem 421(1), 158–163

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12770827 [13]] Pyung Cheon Lee, et al 2003 "Biosynthesis of Structurally Novel Carotenoids in Escherichia coli" Chemistry & Biology 10, 453–462

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Metabolic+Engineering+7%2C+18%E2%80%9326 [14]] Pyung Cheon Lee, et al "Directed evolution of Escherichia coli farnesyl diphosphate synthase (IspA) reveals novel structural determinants of chain length specificity" Metabolic Engineering 7, 18–26

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Journal+of+Antimicrobial+Chemotherapy+47%2C+565-573 [15]] Shigeru Inoue, et al 2001 "Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their major constituents against respiratory tract pathogens by gaseous contact" Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 47, 565-573

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2587246 [16]] J. Grimberg, et al 1989 "A simple method for the preparation of plasmid and chromosomal E. coli DNA." Nucleic Acids Research 17, 21

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17576428 [17]] Jonathan Gershenzon, et al 2007 "The function of terpene natural products in the natural world." NATURE CHEMICAL BIOLOGY 3(7), 408-414