Difference between revisions of "Team:ETH Zurich/Modeling"

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/7/7f/ETH_GFP_percell_everything.gif" style="width:100%"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/7/7f/ETH_GFP_percell_everything.gif" style="width:100%"> | ||

</a> | </a> | ||

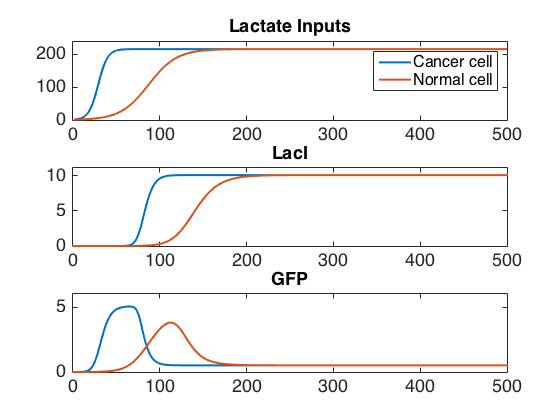

| − | <p><b>Figure 7.</b> GFP concentration over time in four cases: A) Cancer cell | + | <p><b>Figure 7.</b> GFP concentration over time in four test cases: A) Cancer cell with bound <i>E. coli</i> cells B) Cancer cell with unbound <i>E. coli</i> C) Normal cell with bound <i>E. coli</i> D) Normal cell with floating <i>E. coli</i></p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

Revision as of 01:58, 19 September 2015

- Project

- Modeling

- Lab

- Human

Practices - Parts

- About Us

Modeling

Introduction

Our system consists of two modules that sense different general cancer markers (increased lactate production and phosphatidylserine display on the outer side of the cell membrane due to sTRAIL-induced apoptosis) and produces a strong signal only when both are present. The genetic circuit is designed as a signalling chain, with a lactate sensor triggering the amplification of AHL production which is sensed by neighboring E. coli cells. When AHL becomes sufficiently concentrated, it triggers the production of a fluorescent signal (GFP). Overall, this chain acts like an AND gate of the two signals (see Figure 1).

The two modules of our genetic design (see Figure 2) were modeled and tested independently before being merged into a single model of the whole system. Each module was first evaluated and characterized at the single cell level in MATLAB in order to evaluate their initial states, steady states, and to study their dynamics. Then, each module was implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics to characterize their spatial and temporal behavior, and to implement additional biological properties of our system.

The final result is a model providing a reasonable approximation of the behavior of our system under our test conditions. In addition, our characterization of the lactate module is a significant contribution to the understanding of this system.

Goals

- Studying the fold-change sensor.

- Check different approaches for the control of the quorum sensing module.

- Determine conditions in which our system works as an AND gate

- Implementing a reaction-diffusion model to feature biological properties of our system deployed within different microfluidic chip designs.

- Aiding in the characterization of our biological parts, such that we can perform in silico experiments and optimize our biological and chip designs.

Lactate module

The lactate sensor is a fold-change sensor with the topology of an incoherent feed-forward loop. As shown in Figure 3, LuxR production is repressed by both LacI and LldR (the feed-forward), but LacI is produced when LldR binds lactate and is no longer a repressor. When the activation of LacI is delayed relative to the action of LldR on the promoter of LuxR, the action of lactate produces a pulse of LuxR whose amplitude depends on the rate of lactate production until LacI becomes active.

Due to the lack of a quantitative characterization of LldR's function, a reasonable subspace of parameters for the system had to be estimated before lab results could be used to determine them.

When the sensor was implemented in a reaction-diffusion model with cells that take up lactate at rates dependent on their proximity to a lactate producer, a higher rate of LuxR production was observed in the proximal cells with dynamics resembling the production phase predicted in the single cell model.

AHL module

The quorum sensing module is based on the LuxR-AHL system. In our system, the complex of LuxR with N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) promotes the transcription of LuxI and our signalling GFP. LuxI produces AHL that can bind to more LuxR, creating a positive feedback loop. This system relies on the leaky expression of LuxI to produce an initial concentration of AHL, but this leakiness also means that when run in a small volume, our system will self-activate after some time. Since our E. coli are expected to colocalize around cancer cells by binding to them, their proximity leads to a slight concentration of AHL in complex with LuxR around the cancer cell, leading to increased LuxI and GFP production and shortening the self-activation time.

The LuxR-AHL system is well characterized in the literature, so modeling efforts focused on determining its self-activation properties under various conditions. The binding of a layer of E. coli to the surface of a target mammalian cell within a 1 nL well is abstracted to a central sphere (representing the target cell) surrounded by an outer layer representing the bound cells (referred to as the doughnut). The remaining space represents the unbound cells and the rest of the well's volume and is referred to as the bulk. Simulating this module in this abstract geometry and in a simplified disconnected compartment model showed that the generation of a gradient of total AHL is only possible through the capture of AHL by its complex with LuxR and that increasing the size of the well lengthened the self-activation time.

Combined model with other biological features

Figure 7. GFP concentration over time in four test cases: A) Cancer cell with bound E. coli cells B) Cancer cell with unbound E. coli C) Normal cell with bound E. coli D) Normal cell with floating E. coli

After the modules were implemented and tested independently, their combination was implemented in both the compartment and reaction-diffusion models. In the compartment model, the case where E. coli cells bound to a cancer cell target activated first, while the other cases exhibited intermediate behavior by activating later, but all converging to the same steady-state GFP concentrations. The activation times for each case were separated by approximately 100 minutes. The optimal ratio of GFP concentration between bound and unbound cells was obtained within a certain range of lactate production rates and at higher densities of bound E. coli.

In the reaction-diffusion model of the combined genetic circuit, additional biological properties of our cells were implemented. These included simulating the logistic growth of the E. coli population, the cell's lactate uptake dynamics, and the consequences of performing the experiment in a water droplet suspended in an oil flow. The final result was a greater GFP concentration ratio and a slower signal production rate that did not reach steady-state in the timeframe of the simulation. In both models, the combined system acts as an AND gate on our input signals.

Conclusions

We characterized our system by simulating its modules separately and together through a series of increasingly-complex models. We show that under certain parameters, our lactate module is able to produce LuxR at a concentration dependent on the rate of lactate production. Simulation of the AHL module with a simplified compartment model and with a more accurate reaction-diffusion model show that AHL is able to diffuse through the entire experiment well in a time on the order of a few minutes and that the self-activation time of the system is dependent on the volume of the well. In both the simplified compartment model and the more realistic reaction-diffusion models, a measurably stronger GFP signal was produced in the wells where E. coli bound to a cancer cell within long timeframe. This demonstrates the viability of our system as a specific CTC detection system utilizing these two general cancer markers.