Difference between revisions of "Team:EPF Lausanne/Design"

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

<br> <br> | <br> <br> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | We addressed these issues using dCas9-w to build a functional bio-transistor. This catalytically dead version of Cas9 lacks the ability to cleave DNA, but can still bind it in a guided fashion. Recognition of the target sequence is mediated by a guide RNA (gRNA) moiety. We fused dCas9 to a RNA Polymerase (RNAP) recruiting element, the w(omega) subunit. Depending on where dCas9-w binds a promoter, it will either activate or inhibit transcription. At an optimal distance upstream from the transcriptional starting site (TSS), the w subunit recruits RNAP activating the transcription of the associated gene. However, when closer to the TSS, dCas9-w sterically hinders RNAP action, thus inhibiting transcription. | + | We addressed these issues using dCas9-w to build a functional bio-transistor. This catalytically dead version of Cas9 lacks the ability to cleave DNA, but can still bind it in a guided fashion. Recognition of the target sequence is mediated by a guide RNA (gRNA) moiety. We fused dCas9 to a RNA Polymerase (RNAP) recruiting element, the w (omega) subunit. Depending on where dCas9-w binds a promoter, it will either activate or inhibit transcription. At an optimal distance upstream from the transcriptional starting site (TSS), the w subunit recruits RNAP activating the transcription of the associated gene. However, when closer to the TSS, dCas9-w sterically hinders RNAP action, thus inhibiting transcription. |

</p> | </p> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

<figcaption> <b></b> </figcaption> | <figcaption> <b></b> </figcaption> | ||

</figure></center> | </figure></center> | ||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br><br><br> | <br><br><br> | ||

| − | In a | + | In a classical biologic circuit, the transistor is composed of a promoter regulating an output gene. The input signal is incorporated by a protein regulating the promoter. In dCas9-w bio-transistors, regulatory proteins are replaced by small gRNAs targeting the promoter. The modularity of gRNA sequences makes the multiplication of analog transistors possible and faster. Thanks to their similarity, dCas9-w - sgRNA complexes behave in an homogeneous fashion, and the specificity of the gRNA prevents cross-talk between different transistors. Our team therefore confirmed following features: </br> |

</p> <ul> | </p> <ul> | ||

<li> Inducibility of the promoter </li> | <li> Inducibility of the promoter </li> | ||

| − | <li> Homogeneity </li> | + | <li> Homogeneity: Mutability of the promoter </li> |

<li> Orthogonality </li> | <li> Orthogonality </li> | ||

<li> Chainability </li> | <li> Chainability </li> | ||

| Line 118: | Line 117: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| − | <h2> Homogeneity </h2> | + | <h2> Homogeneity: Mutability of the promoter </h2> |

<p>Logic gates and more complex circuits are composed of several transistors. Therefore we had to prove the activation/inhibition results we obtained were reproducible with a mutated version of the promoter. We changed the inhibitory and activating sequences on the promoter along with associated gRNAs. Figure 2 shows activation (A_alt) and inhibition (R1_alt and R2_alt) worked as expected. Unlike for the first tested promoter, inhibition is this time lower than the basal level (B_alt) but remains close to it. However, the overall pattern is well conserved. | <p>Logic gates and more complex circuits are composed of several transistors. Therefore we had to prove the activation/inhibition results we obtained were reproducible with a mutated version of the promoter. We changed the inhibitory and activating sequences on the promoter along with associated gRNAs. Figure 2 shows activation (A_alt) and inhibition (R1_alt and R2_alt) worked as expected. Unlike for the first tested promoter, inhibition is this time lower than the basal level (B_alt) but remains close to it. However, the overall pattern is well conserved. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| Line 160: | Line 159: | ||

<h2> Orthogonality </h2> | <h2> Orthogonality </h2> | ||

| − | <p>We tested the effect of non-complementary gRNAs on transistors controlling GFP. The output fluorescence levels are similar between each other and close to the basal level. This proves inputs are specific to their transistor which is a strong hint at the robustness of our system. | + | <p>We tested the effect of non-complementary gRNAs on transistors controlling GFP. The output fluorescence levels are similar between each other and close to the basal level (Fig. 3). This proves inputs are specific to their transistor which is a strong hint at the robustness of our system. |

</p> | </p> | ||

<center><figure> | <center><figure> | ||

| Line 188: | Line 187: | ||

<br> <br> | <br> <br> | ||

<h2> Chainability </h2> | <h2> Chainability </h2> | ||

| − | <p>To test the chainability of biotransistors, the following construct (FIg. | + | <p>To test the chainability of biotransistors, the following construct (FIg. 4) was induced with sgRNA x0 etc. Inducing the upstream transistor successfully resulted in induction of downstream transistor (A_u) to levels comparable to direct activation of J23117_alt (A_alt). We notice that the basal expression of the downstream reporter J23117_alt in chained configuration (B_d) is higher than the basal expression of regular J23117_alt (B_alt). This is probably due to leakage from the upstream promoter, as repressing the upstream promoter (R_u) resulted in lower fluorescent output. We therefore believe that our transistors could be chained to form more complex circuits. As far as we know, chaining dCas9-w-regulated promoters hadn’t been attempted. This might be the first exclusively dCas9-based bio-circuit in E. coli ! |

</p> | </p> | ||

<center><figure> | <center><figure> | ||

Revision as of 03:04, 19 September 2015

Overview

Currently, genetic circuits reproducing digital logic are limited in the multiplication and chaining of logic elements as each step requires a different signaling molecule. This triggers an inhomogeneous response and exposes the logic circuit to crosstalk.

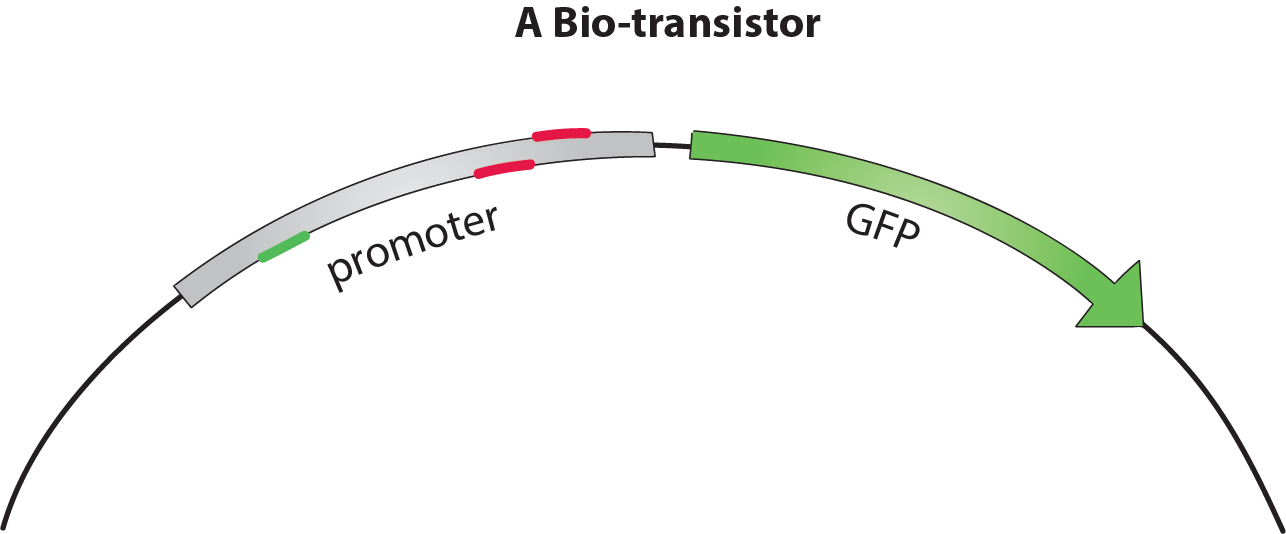

We addressed these issues using dCas9-w to build a functional bio-transistor. This catalytically dead version of Cas9 lacks the ability to cleave DNA, but can still bind it in a guided fashion. Recognition of the target sequence is mediated by a guide RNA (gRNA) moiety. We fused dCas9 to a RNA Polymerase (RNAP) recruiting element, the w (omega) subunit. Depending on where dCas9-w binds a promoter, it will either activate or inhibit transcription. At an optimal distance upstream from the transcriptional starting site (TSS), the w subunit recruits RNAP activating the transcription of the associated gene. However, when closer to the TSS, dCas9-w sterically hinders RNAP action, thus inhibiting transcription.

In a classical biologic circuit, the transistor is composed of a promoter regulating an output gene. The input signal is incorporated by a protein regulating the promoter. In dCas9-w bio-transistors, regulatory proteins are replaced by small gRNAs targeting the promoter. The modularity of gRNA sequences makes the multiplication of analog transistors possible and faster. Thanks to their similarity, dCas9-w - sgRNA complexes behave in an homogeneous fashion, and the specificity of the gRNA prevents cross-talk between different transistors. Our team therefore confirmed following features:

- Inducibility of the promoter

- Homogeneity: Mutability of the promoter

- Orthogonality

- Chainability

Experimental validation

Inducibility of the promoter

To verify induction and repression by dCas9-w, we targeted a GFP controlling promoter once with an activating sgRNA and once with an inhibitory one. Figure 1 shows the GFP level is increased when placing dCas9-w on the activating position (A). Inhibition (R1 and R2) is slightly higher than basal level of fluorescence. This could be explained by the great tightness of J23117 promoter (link Interlab) and by a small leakage due to the presence of the w subunit. To prove an inhibitory sgRNA triggers fluorescence repression, we tested activating and inhibiting the gene at the same time (A/R1 and A/R2). We saw a clear decrease of fluorescence compared to the fully activated state.

Homogeneity: Mutability of the promoter

Logic gates and more complex circuits are composed of several transistors. Therefore we had to prove the activation/inhibition results we obtained were reproducible with a mutated version of the promoter. We changed the inhibitory and activating sequences on the promoter along with associated gRNAs. Figure 2 shows activation (A_alt) and inhibition (R1_alt and R2_alt) worked as expected. Unlike for the first tested promoter, inhibition is this time lower than the basal level (B_alt) but remains close to it. However, the overall pattern is well conserved.

Orthogonality

We tested the effect of non-complementary gRNAs on transistors controlling GFP. The output fluorescence levels are similar between each other and close to the basal level (Fig. 3). This proves inputs are specific to their transistor which is a strong hint at the robustness of our system.

Chainability

To test the chainability of biotransistors, the following construct (FIg. 4) was induced with sgRNA x0 etc. Inducing the upstream transistor successfully resulted in induction of downstream transistor (A_u) to levels comparable to direct activation of J23117_alt (A_alt). We notice that the basal expression of the downstream reporter J23117_alt in chained configuration (B_d) is higher than the basal expression of regular J23117_alt (B_alt). This is probably due to leakage from the upstream promoter, as repressing the upstream promoter (R_u) resulted in lower fluorescent output. We therefore believe that our transistors could be chained to form more complex circuits. As far as we know, chaining dCas9-w-regulated promoters hadn’t been attempted. This might be the first exclusively dCas9-based bio-circuit in E. coli !