Difference between revisions of "Team:DTU-Denmark/Project/POC MAGE"

| Line 189: | Line 189: | ||

<li > | <li > | ||

<a href="/Team:DTU-Denmark/Achievements" | <a href="/Team:DTU-Denmark/Achievements" | ||

| − | > | + | >Key Achievements |

</a></li> | </a></li> | ||

<li > | <li > | ||

Latest revision as of 04:00, 19 September 2015

Proof of concept of MAGE in B. subtilis

Overview

In order for MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) to work at a high efficiency, a strain with inserted recombinase and inhibited or knocked out mismatch repair gene has to be used [1]. In our project, two different recombinases were used: a recombination protein Beta from the E. coli phage Lambda, which was codon optimized for B. subtilis 168, and GP35, a recombinase from the B.subtilis phage SPP1 [2]. The mismatch repair proteins known as MutS and MutL were knocked out by transforming pSB1C3_recombinase plasmid into the B. subtilis W168. Since the MutL protein is dependent on the binding of MutS, the knockout of the mutS disables the function of the MutL protein [3].

Four Bacillus subtilis strains which expressed a recombinase were created by genetically engineering the wild type strain 168:

- ∆amyE::beta-neoR

- ∆amyE::GP35-neoR

- ∆mutS::beta-neoR

- ∆mutS::GP35-neoR

For proof of concept we decided to make a single protein substitution in the ribosomal S12 protein in B. subtilis results in resistance to the antibiotic streptomycin. The required change is a lysine to arginine substitution at position 56 of the protein. The S12 subunit is coded by the rpsL gene [4]. An oligo that could integrate this change was design using MODEST [5]. These oligos were successfully integrated into the two strains: ∆mutS::beta-neoR and ∆mutS::GP35-neoR.

Achievements

- Made Bacillus subtilis 168 WT MAGE compatible

- Showed that the MODEST program can make oligoes that can be inserted in Bacillus. subtilis 168.

- Introducing Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) in Bacillus subtilis 168.

MAGE competent strains

All the strain were made by homologous recombineering. Plasmids containing cassettes that were able to do a double-crossover homologous recombineering into the genome of B. subtilis 168 (referred to as knockout (KO) plasmid). These were used to, simultaneously, delete the desired gene (amyE or mutS) and inserting the expression cassette for one of the recombinases: beta or GP35.

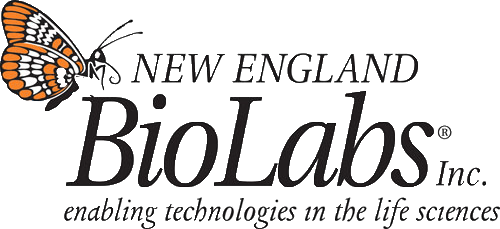

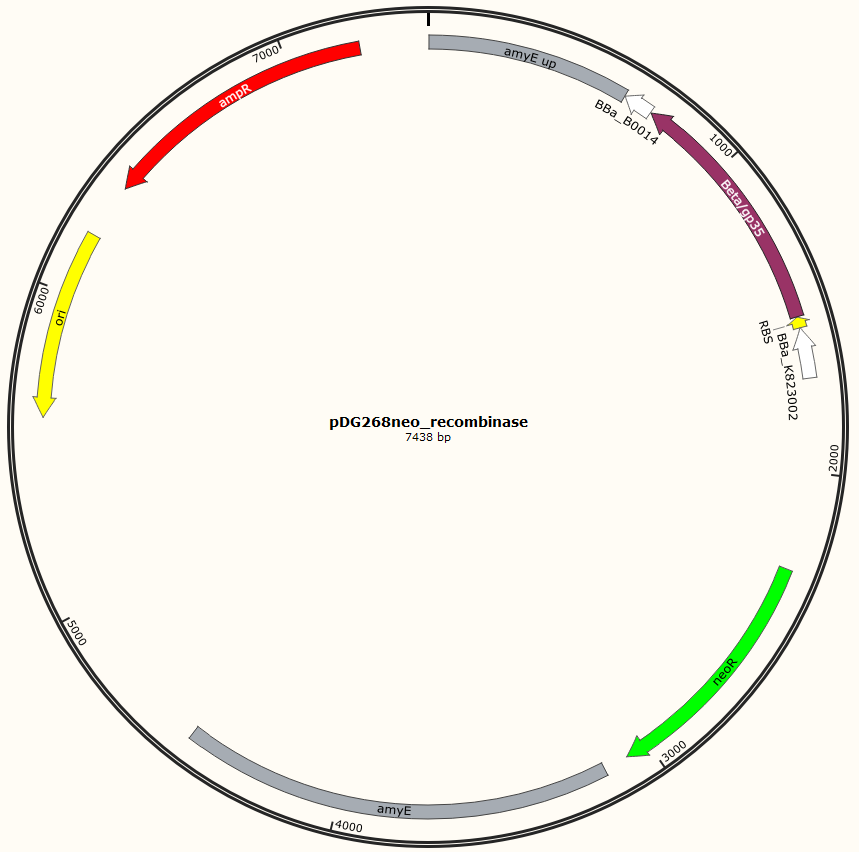

Figure 1. Shows the general concepts of the two plasmids pDG268neo_recombinase and pSB1C3_recombinase. Both exist in two versions, one with each of the recombinase proteins CDSs (Beta and GP35). They also have different RBSs since they are optimized for the CDS. Upstream of neoR is a promoter and RBS and downstream of neoR is a terminator, but sequences and positions of these features are not known.

Four different plasmids were assembled to make the four MAGE ready strains:

pDG268neo_Beta-neoR

pDG268neo_GP35-neoR

pSB1C3_Beta-neoR

pSB1C3_GP35-neoR

For pDG268neo_recobinase a DNA sequence containing following features

● Promoter: PliaG from BBa_K823002 was used.

● RBSs were optimized for the specific CDS using the salis lab RBS calculator (https://www.denovodna.com/software/)

● CDS for recombination protein beta or GP35

● Terminator: we use rho-independent Part:BBa_B0014

Download gblocks hereSequence was ordered from IDT as two gblocks (for each recombinase) with overlapping regions, thus they can be assembled with Gibson assembly.

pDG268neo was linearized in a PCR with primers, so that the native lacZ was omitted. This linearized plasmid was purified and used in a Gibson assembly reaction with two cognate gblocks.

Figure 2. Gibson assembly of the pDG268neo_GP35, the gblocks was fused to the “gp35 Gblocks fused” in the same reaction. The Gibson assembly of pDG268neo_beta was similar.

This resulted in two different plasmids pDG268neo_beta and pDG268neo_gp35.

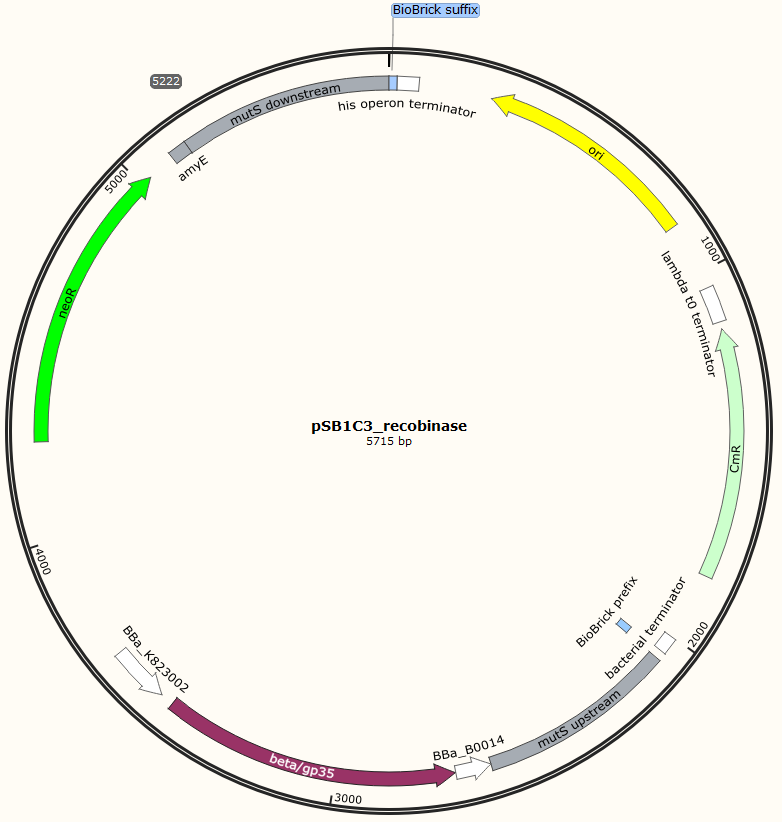

The two mutS KO plasmids was made of the following DNA fragments:

1. About 500 bp up- and downstream from mutS was amplified, using primers with tails.

2. Recombinase and neoR expression cassettes was amplified from the pDG268neo_recombinase

3. Linearized pSB1C3 was used as template.

These fragments was assembled into two different plasmids pSB1C3_mutS::beta-neoR and pSB1C3_mutS::gp35-neoR using Gibson assembly.

Figure 3. Gibson assembly of the pSB1C3_beta. The feature called “mutL” corresponding mutS downstream. The Gibson assembly of pSB1C3_GP35 was similar.

All plasmids were verified by restriction enzyme digestion.

We prepared naturally competent B. subtilis 168 to be transformed. The plasmids were linearized with restriction enzymes. Then transformed into naturally competent B. subtilis 168, transformants were selected on 5ɣ neo. Transformants were verified with colony PCRs.

Methods for proof of concept

Electroporation competent cells were prepared in following the protocol: Electroporation competent Bacillus subtilis 168. Electropration was carried out according to the MAGE in Bacillus subtilis 168 protocol. The colonies from the LB plates were colonies picked onto an LB and LB + 500y streptomycin (strep) plates. Plates were incubated at 37 degC for 48 hours and CFUs were counted on both the LB and the strep plates.Results

| Total number of CFUs | Number of transformant | Transformation frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔmutS::beta-neoR | 52 | 7 | 0.13 |

| ΔmutS::GP35-neoR | 100 | 1 | 0.01 |

Table 1. shows the data for the MAGE proof of concept.

Second replication of the plates:

Figure 4. Pictures shows the first and second replication of the transformants. From left to right of ΔmutS::GP35-neoR replicate1, ΔmutS::GP35-neoR replicate2 , ΔmutS::beta-neoR replica1, and ΔmutS::beta-neoR replica2.

Discussion

The results of this proof of concept indicates that MAGE works in two of the MAGE compatible strains ΔmutS::beta-neoR and ΔmutS::GP35-neoR. More thorough experiments need to be done. The results suggest that the beta protein is a more effective recombinase for the type of oligo used in this experiment.

References

- Carr, P. A., Wang, H. H., Sterling, B., Isaacs, F. J., Lajoie, M. J., Xu, G., … Jacobson, J. M. (2012). Enhanced multiplex genome engineering through co-operative oligonucleotide co-selection. Nucleic Acids Research, 40(17). doi:10.1093/nar/gks455

- Sun, Z., Deng, A., Hu, T., Wu, J., Sun, Q., Bai, H., … Wen, T. (2015). A high-efficiency recombineering system with PCR-based ssDNA in Bacillus subtilis mediated by the native phage recombinase GP35. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 99(12), 5151–5162. doi:10.1007/s00253-015-6485-5

- Ginetti, F., Perego, M., Albertini, A. M., & Galizzi, A. (1996). Bacillus subtilis mutS mutL operon: Identification, nucleotide sequence and mutagenesis. Microbiology, 142(8), 2021–2029. doi:10.1099/13500872-142-8-2021

- Barnard, A. M. L., Simpson, N. J. L., Lilley, K. S., &amp; Salmond, G. P. C. (2010). Mutations in rpsL that confer streptomycin resistance show pleiotropic effects on virulence and the production of a carbapenem antibiotic in Erwinia carotovora. Microbiology, 156(4), 1030–1039. &lt;a href=&#34;http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.034595-0&#34; target=&#34;_blank&#34;&gt;doi:10.1099/mic.0.034595-0&lt;/a&gt;

- Bonde, M. T., Klausen, M. S., Anderson, M. V., Wallin, A. I. N., Wang, H. H., & Sommer, M. O. A. (2014). MODEST: a web-based design tool for oligonucleotide-mediated genome engineering and recombineering. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(W1), W408–W415. doi:10.1093/nar/gku428

Department of Systems Biology

Søltofts Plads 221

2800 Kgs. Lyngby

Denmark

P: +45 45 25 25 25

M: dtu-igem-2015@googlegroups.com