Difference between revisions of "Team:Austin UTexas/Project/Problem"

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Our projects focused on monitoring device stability and determining what kinds of sequences and sequence features contribute to device instability. <b>We wish to identify and better characterize sequences that contribute to the relative instability of genetic devices so they can be used to predict device longevity, as well as be taken into account when creating and modifying such devices</b>. In the spring of 2015, UT iGEM team members, assisted by the UT Austin Freshman Research Initiative stream "Hijacking Cell Factories for Synthetic Biology," utilized the EFM calculator to identify sequences within fluorescent protein coding genes that were more likely to break (mutate). We used this information to form hypotheses and determine which fluorescent protein coding genes in our inventories are the most and least evolutionary stable. Then, we tested the stability of these constructs. | Our projects focused on monitoring device stability and determining what kinds of sequences and sequence features contribute to device instability. <b>We wish to identify and better characterize sequences that contribute to the relative instability of genetic devices so they can be used to predict device longevity, as well as be taken into account when creating and modifying such devices</b>. In the spring of 2015, UT iGEM team members, assisted by the UT Austin Freshman Research Initiative stream "Hijacking Cell Factories for Synthetic Biology," utilized the EFM calculator to identify sequences within fluorescent protein coding genes that were more likely to break (mutate). We used this information to form hypotheses and determine which fluorescent protein coding genes in our inventories are the most and least evolutionary stable. Then, we tested the stability of these constructs. | ||

| − | : '''[[Team:Austin_UTexas/Project/Plasmid_Study | | + | === References === |

| + | |||

| + | # Sleight et al.: Designing and engineering evolutionary robust genetic circuits. Journal of Biological Engineering 2010 4:12. | ||

| + | # “EFMCalculator.” tool from the Barrick Lab: http://barricklab.org/django/efm/ | ||

| + | # Jack et al.: Predicting the genetic stability of engineered DNA sequences with the EFM calculator. Print. 18 Sept. 2015. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | : '''[[Team:Austin_UTexas/Project/Plasmid_Study | Continue to Part 1: BREAKING FLUORESCENT PROTEIN EXPRESSION]]''' | ||

{{Austin_UTexas_Footer}} | {{Austin_UTexas_Footer}} | ||

Revision as of 21:08, 18 September 2015

Problem: Genetic Instability

Background

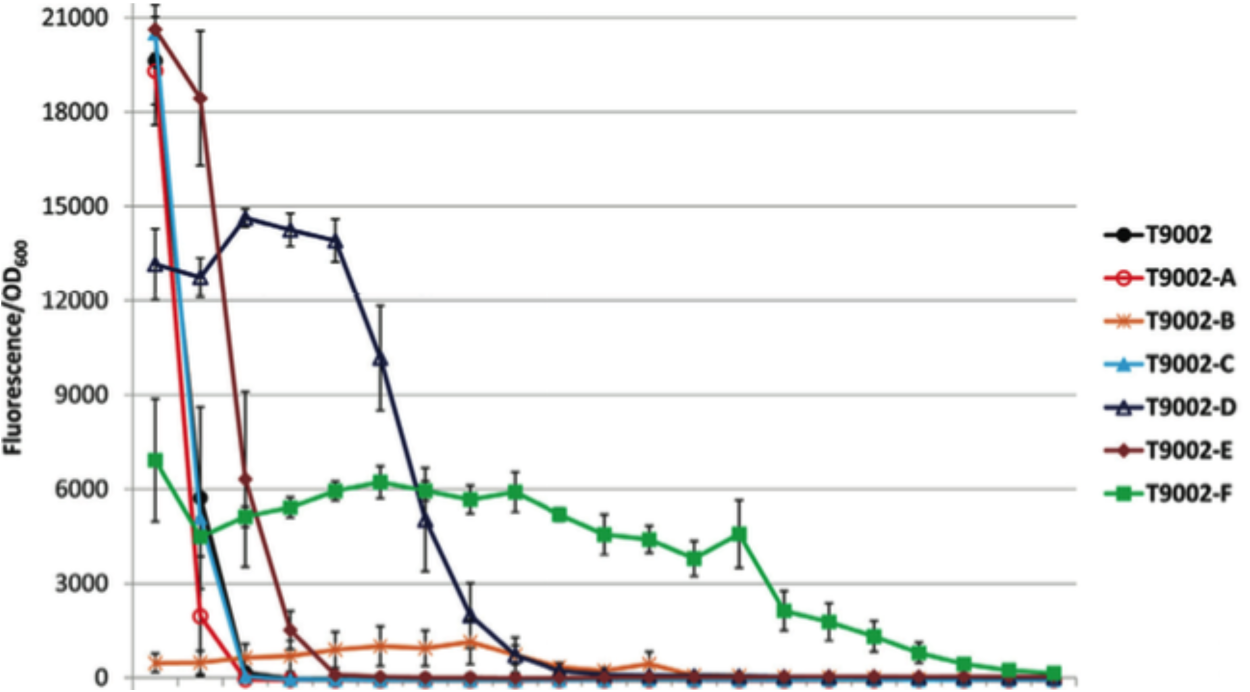

One of the major issues facing genetic engineering is the longevity of genetic devices once inserted into organisms. An organism can be modified, but that does not ensure that the modification will last. Subsequent generations of modified organisms often lose or “break” the genetic device through mutations. Breaking a plasmid or an inserted device often decreases the metabolic load of that organism, giving it a competitive advantage by enabling it to allocate more resources toward replication. This allows them to dominate a population over time.

Previous research has identified several factors that contribute to the breaking of genetic devices. One major factor is the relative fitness of organisms without the device over those with it. Strongly expressed devices will break faster than weakly expressed devices, since devices of the former type place a greater metabolic load on the organism. Similarly, genes that code for 'costly' proteins that may interfere with other cellular functions in ways that are toxic are more likely to break.

Another major factor that contributes to device stability is the rate of mutations leading to device failure. If a device includes DNA sequences that act as mutational hotspots, it may be very unstable. The [http://barricklab.org/django/efm Evolutionary Failure Mode calculator] (developed by the Barrick lab) identifies DNA sequences that are prone to breaking, such as simple sequence repeats and long stretches of a single repeated nucleotide. The EFM calculator gives sequences a relative instability prediction (RIP) score, and higher RIP scores indicate sequences that are more prone to breaking.

Project and Motivation

Our projects focused on monitoring device stability and determining what kinds of sequences and sequence features contribute to device instability. We wish to identify and better characterize sequences that contribute to the relative instability of genetic devices so they can be used to predict device longevity, as well as be taken into account when creating and modifying such devices. In the spring of 2015, UT iGEM team members, assisted by the UT Austin Freshman Research Initiative stream "Hijacking Cell Factories for Synthetic Biology," utilized the EFM calculator to identify sequences within fluorescent protein coding genes that were more likely to break (mutate). We used this information to form hypotheses and determine which fluorescent protein coding genes in our inventories are the most and least evolutionary stable. Then, we tested the stability of these constructs.

References

- Sleight et al.: Designing and engineering evolutionary robust genetic circuits. Journal of Biological Engineering 2010 4:12.

- “EFMCalculator.” tool from the Barrick Lab: http://barricklab.org/django/efm/

- Jack et al.: Predicting the genetic stability of engineered DNA sequences with the EFM calculator. Print. 18 Sept. 2015.