Team:Austin UTexas/Project/Plasmid Study

Observing Fluorescent Gene Stability

Introduction

One of the major issues facing genetic engineering is the overall longevity of genetic devices once inserted into organisms. An organism can be modified, but that does not ensure that the modification will last. Subsequent generations of modified organisms often lose or “break” the genetic device through mutations. Mutations that cause a device to break (or otherwise lose part of their functionality) decrease the metabolic load of that organism. This allows the mutant and its descendants to replicate and grow faster than the originally modified organism, allowing the “broken” mutant to overtake a population.

The stability of the sequence was the focus of our research over the course of the summer. We sought to identify sequences that contribute to the relative instability of genetic devices so they can be used to predict the longevity of a genetic device as well as be taken into account when creating and modifying such devices. In the spring of 2015, E. coli was transformed using various fluorescent genes and monitored for breakage, with varying results depending on the plasmid used. Five fluorescent proteins: Yellow fluorescent protein (BBa_K592101), Super-folder Yellow fluorescent protein (BBa_K864100), Engineered Yellow fluorescent protein (BBa_E0030), Enhanced Cyan fluorescent protein (BBa_E0020), and Blue fluorescent protein (BBa_592100).

Understanding what leads to genetic instability could lead to more stable devices and thus could increase the longevity of genetically modified organisms. Since genetic stability can be problematic for any work involving synthetic biology, we wanted to start by determining what sequence motifs make a genetic device unstable. So, in the spring, we began an experiment to study genetic instability of different plasmids in E. coli. We designed and transformed 14 plasmids into TOP10 E. coli. Then, we propagated the strains until either fluorescence was lost or the experiment was concluded.

Methods

Plasmid Construction

Each plasmid comprised of a [http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB1C3 pSB1C3] backbone, which included a gene for chloramphenicol resistance and has a copy number of 100-300. Further, each plasmid received a promoter, ribosome-binding site, and coding sequence for a fluorescent protein. Plasmids were constructed with standard BioBrick cloning procedures and enzymes. Composite BioBricks were constructed using the following unique BioBrick combinations.

Fig.1:

| Plasmid | Fluorescent Protein BioBrick | Fluorescent Protein | Promoter/RBS BioBrick | Promoter;RBS Strength |

| 1 | BBa_K592100 | BFP | BBa_K608004 | Strong; Weak |

| 2 | BBa_K592100 | BFP | BBa_K608007 | Medium; Weak |

| 3 | BBa_E0020 | ECFP | BBa_K608007 | Medium; Weak |

| 4 | BBa_E0020 | ECFP | BBa_K608003 | Strong; Medium |

| 5 | BBa_E0020 | ECFP | BBa_K608002 | Strong; Strong |

| 6 | BBa_K592101 | YFP | BBa_K608002 | Strong; Strong |

| 7 | BBa_K592101 | YFP | BBa_K608006 | Medium; Medium |

| 8 | BBa_K592101 | YFP | BBa_K608007 | Medium; Weak |

| 9 | BBa_K864100 | SYFP2 | BBa_K608002 | Strong; Strong |

| 10 | BBa_K864100 | SYFP2 | BBa_K314100 | Strong; Very Strong |

| 11 | BBa_K864100 | SYFP2 | BBa_K608006 | Medium; Medium |

| 12 | BBa_E0030 | EYFP | BBa_K608007 | Medium; Weak |

| 13 | BBa_EE030 | EYFP | BBa_K608006 | Medium; Medium |

| 14 | BBa_E0030 | EYFP | BBa_K314100 | Strong; Very Strong |

Several fluorescent protein/promoter+RBS combinations were studied in more than one experiment, which is why each plasmid above is classified as a 'unique' combination.

The BioBricks in each pair were ligated together using T4 DNA Ligase, and transformed into TOP10 E. coli. Prepared cultures were streaked onto LB/chloramphenicol (CAM) agar plates, and were placed in a 37°C incubator overnight. After at least 20 hours, the plates were retrieved, and a single colony was grown overnight in 5 mL of LB/CAM media. After sequence confirming the plasmid in each culture, we froze a fraction of these cells in glycerol at -80° C for storage.

Fluorescence Readings

After we transformed the plasmids into E. coli, we were almost ready to begin the propagation phase of our stability experiment.

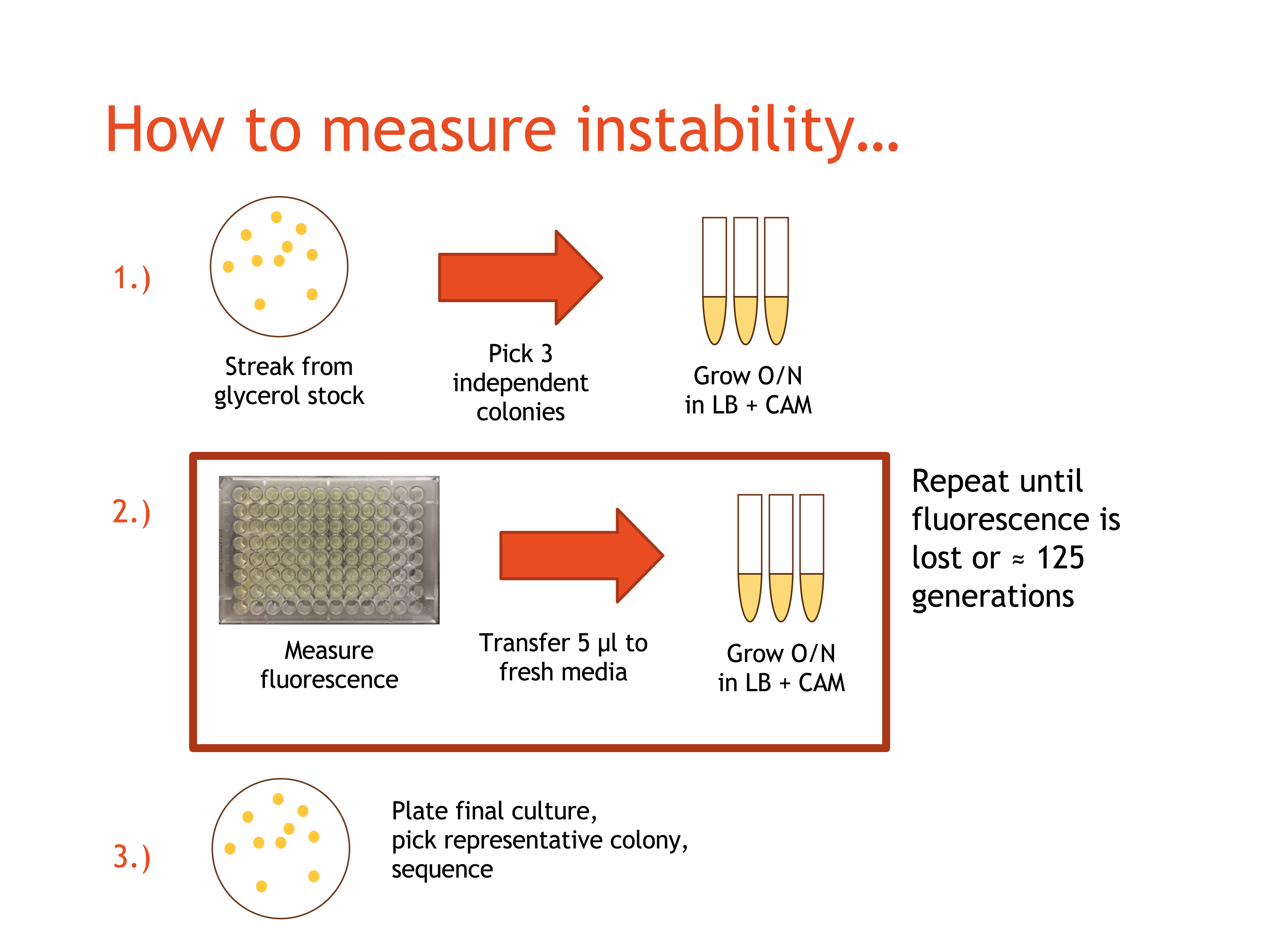

First, we streaked transformed cells for each plasmid onto LB/CAM plates and let them incubate overnight. The next day, we selected a number of independent colonies that were still fluorescing for each plasmid. Then, we placed the colony in 5 mL of LB/CAM media and grew each overnight in the shaker at 37° C and 215 RPM. We refer to these cultures as 'Day 1'. The next day, we began the propagation phase of our experiment.

Moving forward, each day we retrieved the overnight cultures from the shaker. We used 5 μl to start a fresh 5 mL culture with LB/CAM media, which was then grown overnight. Next, we measured fluorescence using a 96 well plate reader by pipetting 200μL from each culture and into a well on a 96-well plate. Finally, the day's cultures were placed in the cold room for storage. This process was repeated until either fluorescence was lost or ten days had past.

After the propagation phase, we sequenced the final cultures and compared this sequence to the original to determine which mutations had dominated the cultures.

Results and Discussion

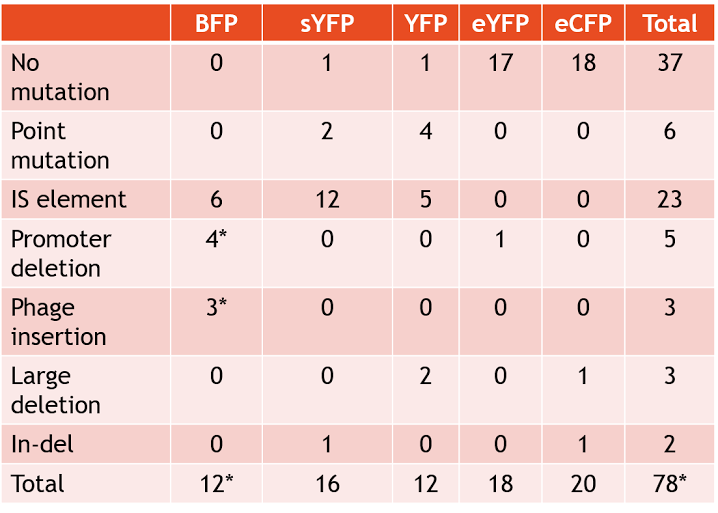

The plasmids created had a great amount of variance in their stability and longevity over the course of the experiment depending on the fluorescent protein that was used in the plasmid.

Plasmids that bore the SYFP2 gene tended to be unstable. Strains with SYFP2 gene frequently broke down within three days, going from very high fluorescence to no observed fluorescence. Furthermore, some samples of SYFP2 lost functionality after merely a day, showing the SYFP2 gene is very unstable across generations. The SYFP2 plasmids most often accumulated IS (insertion sequence) element inserts, which completely prevented the expression of the fluorescent protein. The most common IS elements observed were IS10R and IS10L. Furthermore, S10L/R expressed preference for a particular nucleotide location (GGCGTAGTACC) within the SYFP2 gene. Two point mutations were also independently observed in two samples of SYFP2. One mutation converted resulted in the loss of a start codon.

Plasmids that contain the YFP gene also tended to display instability. Samples with the YFP gene often broke after approximately five days, and a myriad of mutations appeared to have contributed to this instability. IS elements were another common feature among the YFP group. Point mutations in various locations also appeared in the YFP group, such as in the promoter and ribosome binding site. Two samples also featured a large deletion from the plasmid.

The BFP group of plasmids also had high instability, similar to the SYFP2 group of plasmids. This group of plasmids lasted around only a few days before their devices broke. IS elements were very common in the BFP plasmid group along with promoter deletions.

Interestingly, the EYFP and ECFP plasmid groups were incredibly stable, remaining fluorescent for over ten days. Only one sample in the entire EYFP group displayed a mutation, which was a promoter deletion. Only two mutations were shown in the entire ECFP group, a large deletion and an In-del mutation. Overall, these two fluorescent proteins have shown to be very stable (see Table 1 for full results of mutations).

Based on the patterns of mutations, it is clear that IS elements are a major source of instability in plasmids in this strain of E. coli, Top10. Furthermore, because of the common location of insertion for IS elements, they must have a sequence preference. By changing the sequence, it it may be possible to increase the stability of plasmids by eliminating a primary source of mutation. Furthermore, by elucidating the contribution that IS elements make towards the instability, we can anticipate these events and account for such instabilities when designing plasmids for future experiments.

One of our team members also developed a Computational Approach to categorizing the mutations. We believe this will be of great help to us as we begin to analyze our larger data set(s).