Difference between revisions of "Team:Sydney Australia/Description"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Sydney_Australia}} | {{Sydney_Australia}} | ||

| − | + | __NOTOC__ | |

<h2>'''The Problem'''</h2> | <h2>'''The Problem'''</h2> | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

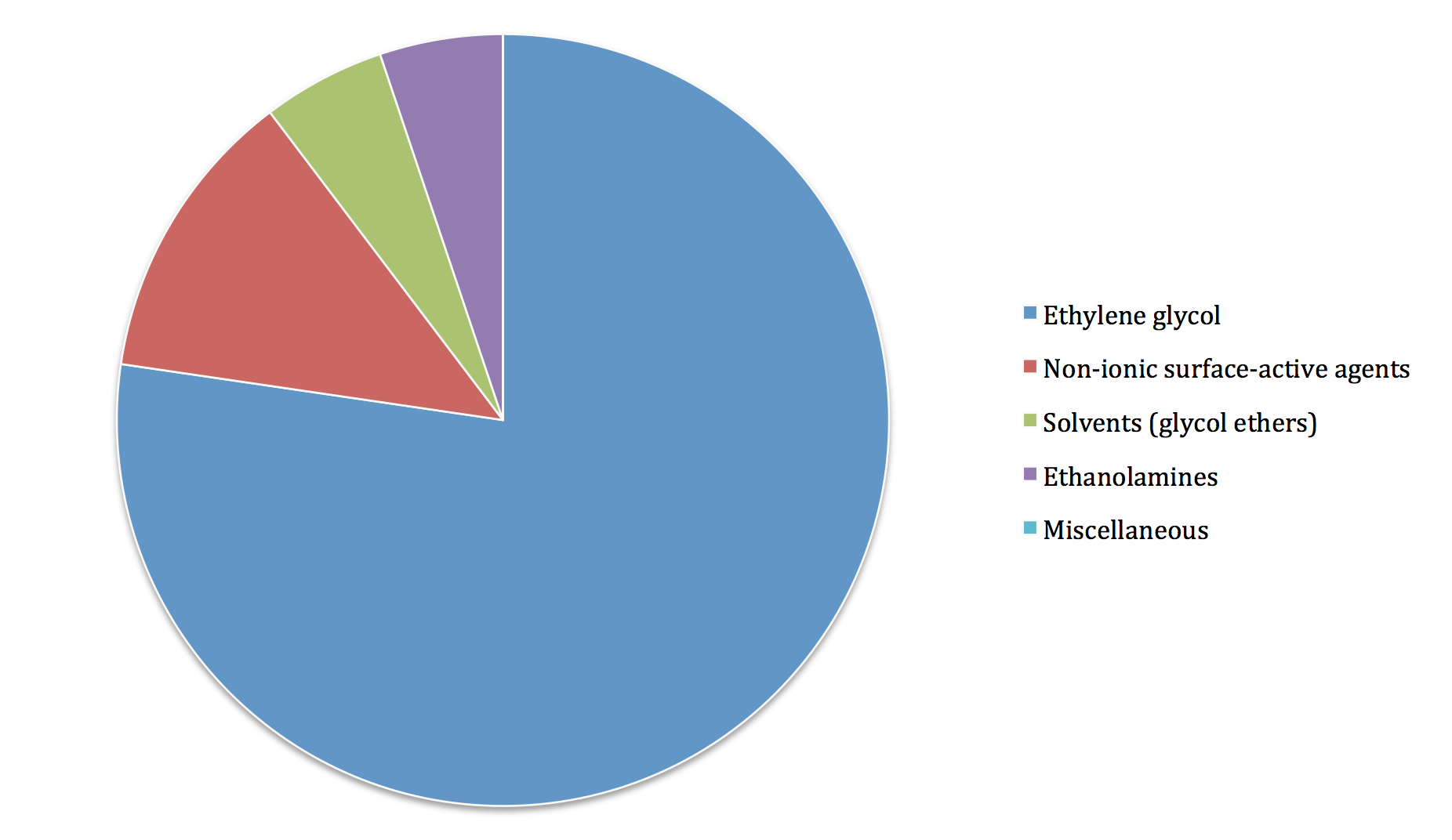

In 1859 the French chemist Charles-Adolphe Wurtz first chemically synthesised ethylene oxide (also known as oxirane) from ethylene chlorohydrin and aqueous potassium hydroxide, unlocking a compound that has been extensively utilized in the pharmaceutical, medical, and manufacturing industry. <sup>1</sup> From sterilising medical equipment to producing ethylene glycol (antifreeze), and as a versatile intermediate for pharmaceutical products, ethylene oxide is essential in many products we use.<sup>2</sup> Indeed, in 1992, the world production of ethylene oxide was about 9.6 x 10<sup>6</sup> metric tons, and that number has no doubt been increasing.<sup>3</sup> | In 1859 the French chemist Charles-Adolphe Wurtz first chemically synthesised ethylene oxide (also known as oxirane) from ethylene chlorohydrin and aqueous potassium hydroxide, unlocking a compound that has been extensively utilized in the pharmaceutical, medical, and manufacturing industry. <sup>1</sup> From sterilising medical equipment to producing ethylene glycol (antifreeze), and as a versatile intermediate for pharmaceutical products, ethylene oxide is essential in many products we use.<sup>2</sup> Indeed, in 1992, the world production of ethylene oxide was about 9.6 x 10<sup>6</sup> metric tons, and that number has no doubt been increasing.<sup>3</sup> | ||

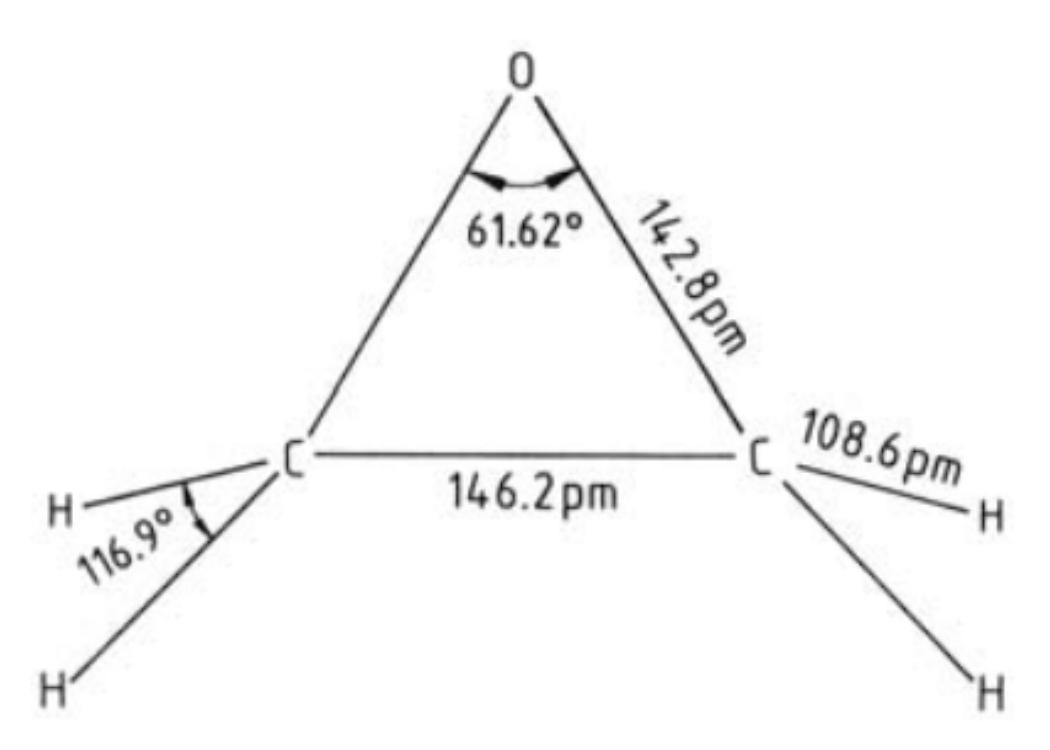

| − | Traditionally, ethylene oxide has been produced through a chlorohydrin process | + | Traditionally, ethylene oxide has been produced through a chlorohydrin process. This process was replaced by the complete oxidation process, pioneered by Theodore Lefort in 1931.<sup>4</sup> Since the production of ethylene oxide, chemists have successfully synthesised other epoxides including propylene oxide. Epoxides are incredibly versatile due to the addition of the oxygen atom on the tetrahedral ring making the compound strained and unstable. <sup>5</sup> Consequently the ring can be easily opened up, releasing abundant amounts of energy that can be used in further reactions, such as nucleophilic addition, hydrolysis and reduction.<sup>6</sup> |

| − | [[File:structure.jpg | | + | [[File:structure.jpg | 400px | left | thumb | '''Figure 2:'''Structure of ethylene oxide]] |

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

'''In a time where the demand for ethylene oxide is increasing we simply cannot afford to continue using inefficient, environmentally damaging, and expensive methods of chemical synthesis. Thus, the Sydney iGEM team is attempting to utilise the monooxygenase enzymes found in Mycobacterium Smegmatis to perform this reaction in a more efficient and safe manner, for a fraction of the cost.''' | '''In a time where the demand for ethylene oxide is increasing we simply cannot afford to continue using inefficient, environmentally damaging, and expensive methods of chemical synthesis. Thus, the Sydney iGEM team is attempting to utilise the monooxygenase enzymes found in Mycobacterium Smegmatis to perform this reaction in a more efficient and safe manner, for a fraction of the cost.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<h2>'''The Solution'''</h2> | <h2>'''The Solution'''</h2> | ||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

[[File:sydney_structure.png | 200px | right | thumb | '''Figure 3:'''Structure of Ethene Monooxygenase]] | [[File:sydney_structure.png | 200px | right | thumb | '''Figure 3:'''Structure of Ethene Monooxygenase]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<h2>'''Past Work'''</h2> | <h2>'''Past Work'''</h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Monooxygenases catalyse the addition of one oxygen molecule from dioxygen into a substrate, while reducing the residual oxygen to water. Ethene monooxygenase is a member of the group 6 soluble di-iron monooxygenases. These enzymes are characterised by the following arrangement of subunits: a coupling protein and a reductase, as well 4 subunits in (αβ)2 configuration. The α and β make up the hydroxylase component, and the di-iron-containing active site in located within the α subunits. The reductase facilitates electron transfer from NADH and the coupling protein aids in stabilising the transition state. This enzyme has only been characterised in two organisms (Mycobacterium strains TY-6 and NBB4). In nature, ethene monooxygenase will catalyse the initial oxidation of ethene to support growth on this carbon source. <sup>9</sup> | Monooxygenases catalyse the addition of one oxygen molecule from dioxygen into a substrate, while reducing the residual oxygen to water. Ethene monooxygenase is a member of the group 6 soluble di-iron monooxygenases. These enzymes are characterised by the following arrangement of subunits: a coupling protein and a reductase, as well 4 subunits in (αβ)2 configuration. The α and β make up the hydroxylase component, and the di-iron-containing active site in located within the α subunits. The reductase facilitates electron transfer from NADH and the coupling protein aids in stabilising the transition state. This enzyme has only been characterised in two organisms (Mycobacterium strains TY-6 and NBB4). In nature, ethene monooxygenase will catalyse the initial oxidation of ethene to support growth on this carbon source. <sup>9</sup> | ||

| Line 41: | Line 47: | ||

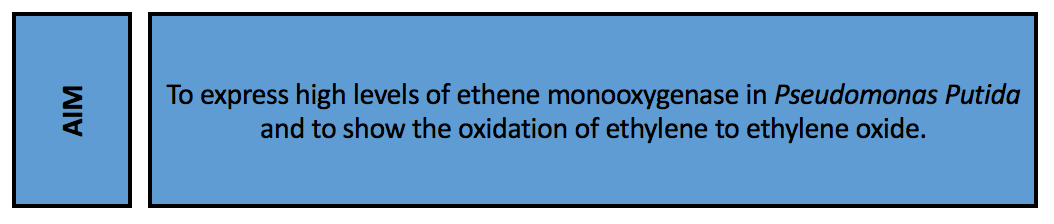

[[File:sydney_aim.png | center | 700px]] | [[File:sydney_aim.png | center | 700px]] | ||

| + | Previous work in the Coleman Laboratory showed ''Pseudomonas putida'' can express low levels of ethene monooxygenase. Thus, we aimed to increase this level of expression. We chose ''Pseudomonas putida'' for two major reasons - | ||

| + | # Fairly novel cloning host which gives our project a unique aspect | ||

| + | # If we are successful, ''psuedomonas'' is a good intermidate host between ''Mycobacterium smegmatis'' and ''Escherichia coli''. | ||

| − | + | [[File:bacteria_sydney.png | center | 800px]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

We '''hypothesised''' that the minimal expression in ''Pseudomonas'' was due to incorrect protein folding and thus our design sought to remedy this. | We '''hypothesised''' that the minimal expression in ''Pseudomonas'' was due to incorrect protein folding and thus our design sought to remedy this. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3> Initial approach </h3> | ||

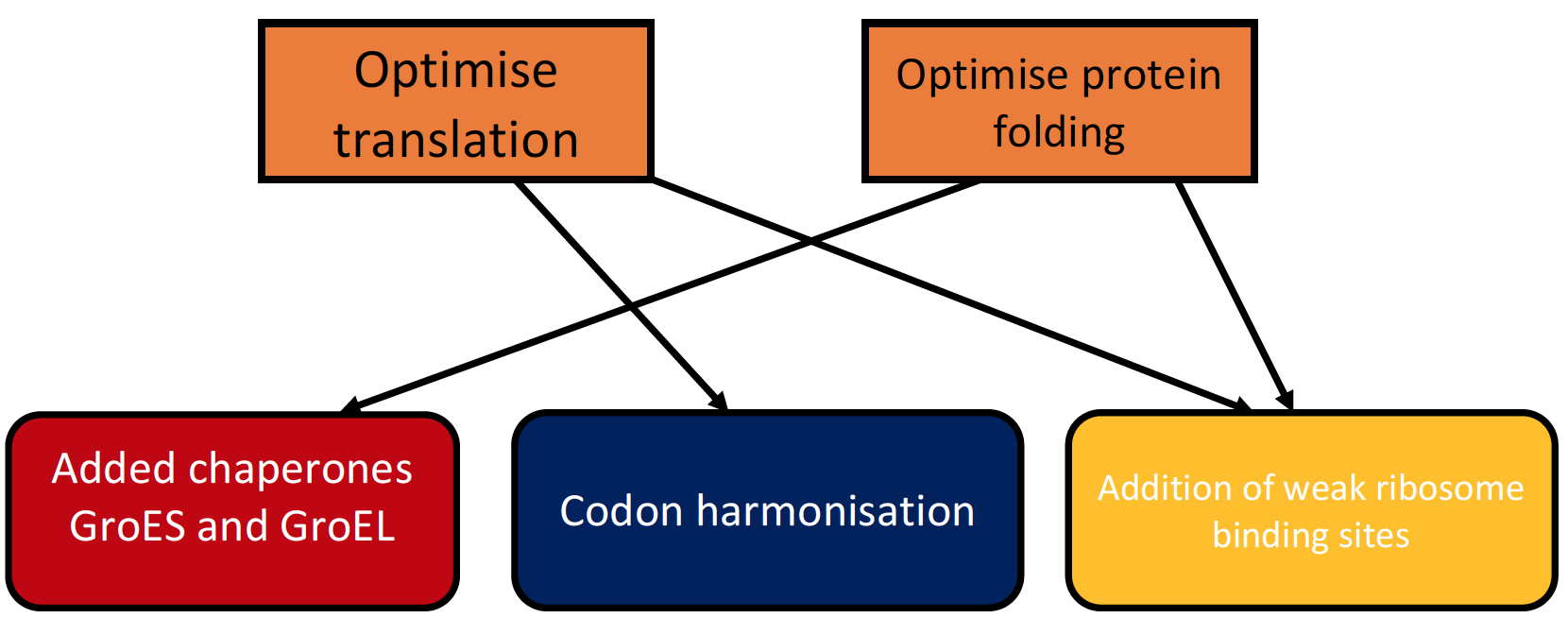

We took a three-pronged approach for optimising expression: | We took a three-pronged approach for optimising expression: | ||

| Line 55: | Line 62: | ||

*Second, we optimised translation through codon harmonisation. This was the major modelling component of our project and more information can be found on the [https://2015.igem.org/Team:Sydney_Australia/Modeling modelling page]. | *Second, we optimised translation through codon harmonisation. This was the major modelling component of our project and more information can be found on the [https://2015.igem.org/Team:Sydney_Australia/Modeling modelling page]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*Third, we optimised translation through adding weak ribosome binding sites. This was undertaken as we hypothesised that translation was occurring too frequently, resulting in ribosomal congestion, and thus the rate of the protein's translation was not regulated correctly. [HARRY - does this new sentence explain it better than the previous one?] | *Third, we optimised translation through adding weak ribosome binding sites. This was undertaken as we hypothesised that translation was occurring too frequently, resulting in ribosomal congestion, and thus the rate of the protein's translation was not regulated correctly. [HARRY - does this new sentence explain it better than the previous one?] | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:sydney_design.png | center | 800px]] |

| + | <h3> Modified approach </h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a result of the negative results we were attaining from the project we modified our apporach around June 2015: | ||

| + | * Remove the chaperones GroES and GroEL | ||

| + | * Attempt LacI co-expression | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 16:38, 15 September 2015

The Problem

In 1859 the French chemist Charles-Adolphe Wurtz first chemically synthesised ethylene oxide (also known as oxirane) from ethylene chlorohydrin and aqueous potassium hydroxide, unlocking a compound that has been extensively utilized in the pharmaceutical, medical, and manufacturing industry. 1 From sterilising medical equipment to producing ethylene glycol (antifreeze), and as a versatile intermediate for pharmaceutical products, ethylene oxide is essential in many products we use.2 Indeed, in 1992, the world production of ethylene oxide was about 9.6 x 106 metric tons, and that number has no doubt been increasing.3

Traditionally, ethylene oxide has been produced through a chlorohydrin process. This process was replaced by the complete oxidation process, pioneered by Theodore Lefort in 1931.4 Since the production of ethylene oxide, chemists have successfully synthesised other epoxides including propylene oxide. Epoxides are incredibly versatile due to the addition of the oxygen atom on the tetrahedral ring making the compound strained and unstable. 5 Consequently the ring can be easily opened up, releasing abundant amounts of energy that can be used in further reactions, such as nucleophilic addition, hydrolysis and reduction.6

Unfortunately, current chemical synthesis processes for epoxides are inefficient, expensive, and use hazardous and non-renewable reagents. The previous chlorohydrin process generated chlorine-containing by-products such as calcium chloride, resulting in pollution. The present oxygen-based oxidation process, whilst more efficient than the chlorohydrin process, has its downfalls. The silver catalyst is highly selective and thus ages quickly, the reaction requires incredibly pure oxygen (99% or greater), and toxic by-products such as formaldehyde are generated. 7 Furthermore, a major disadvantage exists in the lower yield or selectivity of ethylene oxide and the loss of 20-25% of the ethylene to carbon dioxide and water. Thus, the conditions must be tightly controlled to ensure maximum selectivity, making this a high-maintenance process. 8

In a time where the demand for ethylene oxide is increasing we simply cannot afford to continue using inefficient, environmentally damaging, and expensive methods of chemical synthesis. Thus, the Sydney iGEM team is attempting to utilise the monooxygenase enzymes found in Mycobacterium Smegmatis to perform this reaction in a more efficient and safe manner, for a fraction of the cost.

The Solution

Monooxygenase enzymes are capable of performing this epoxide reaction, thus converting alkenes to epoxides safely and efficiently. These biological catalysts are renewable, non-toxic, biodegradable, and can be scaled up for large-volume production.

We are focusing on the enzyme Ethene Monooxygenase due to its ability to catalyse the ethylene to ethylene oxide reaction. To date it has only been found in Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Mycobacteirum is a difficult bacteria to work with as they are slow growing and difficult to work with. Consequently, the team is attempting to achieve high levels of expression in Escherichia Coli.

Past Work

Monooxygenases catalyse the addition of one oxygen molecule from dioxygen into a substrate, while reducing the residual oxygen to water. Ethene monooxygenase is a member of the group 6 soluble di-iron monooxygenases. These enzymes are characterised by the following arrangement of subunits: a coupling protein and a reductase, as well 4 subunits in (αβ)2 configuration. The α and β make up the hydroxylase component, and the di-iron-containing active site in located within the α subunits. The reductase facilitates electron transfer from NADH and the coupling protein aids in stabilising the transition state. This enzyme has only been characterised in two organisms (Mycobacterium strains TY-6 and NBB4). In nature, ethene monooxygenase will catalyse the initial oxidation of ethene to support growth on this carbon source. 9

Our project

Previous work in the Coleman Laboratory showed Pseudomonas putida can express low levels of ethene monooxygenase. Thus, we aimed to increase this level of expression. We chose Pseudomonas putida for two major reasons -

- Fairly novel cloning host which gives our project a unique aspect

- If we are successful, psuedomonas is a good intermidate host between Mycobacterium smegmatis and Escherichia coli.

We hypothesised that the minimal expression in Pseudomonas was due to incorrect protein folding and thus our design sought to remedy this.

Initial approach

We took a three-pronged approach for optimising expression:

- First, we optimised protein folding by adding chaperones GroES and GroEL to encourage correct folding.

- Second, we optimised translation through codon harmonisation. This was the major modelling component of our project and more information can be found on the modelling page.

- Third, we optimised translation through adding weak ribosome binding sites. This was undertaken as we hypothesised that translation was occurring too frequently, resulting in ribosomal congestion, and thus the rate of the protein's translation was not regulated correctly. [HARRY - does this new sentence explain it better than the previous one?]

Modified approach

As a result of the negative results we were attaining from the project we modified our apporach around June 2015:

- Remove the chaperones GroES and GroEL

- Attempt LacI co-expression

1 American Chemistry Council, What is Ethylene Oxide?, 2015, ACC, USA, Accessed 20th of July 2015, http://www.americanchemistry.com/ProductsTechnology/Ethylene-Oxide/What-Is-Ethylene-Oxide.html.

2 Sevas Educational Society, Manufacture of Ethylene Oxide, 2007, SES, Accessed 20th of July 2015, http://www.sbioinformatics.com/design_thesis/Ethylene_oxide/Ethylene-2520oxide_Methods-2520of-2520Production.pdf (p. 2).

3United States Environmental Protection Agency, 1986, Locating and estimating air emission from sources of ethylene oxide, viewed 20th of July 2015, http://www.epa.gov/ttnchie1/le/ethoxy.pdf (p. 11).

4 Wendt HD, Heuvels L, Daatselarr EV, and Schagen TV, 2014, “Industrial production of ethylene oxide” https://www.alembic.utwente.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/LaTeX-example.pdf .

5 Wendt et al, “Industrial production of ethylene oxide”, p.2.

6 Rebsdat S, and Mayer, D, 2012, “Ethylene Oxide”, Ullmann’s Encyclopaedia of Industrial Chemistry, Vol 13, pp 548.

7 Wendt et al, “Industrial production of ethylene oxide”, p.2.

8 Rebsdat S, and Mayer, D, 2012, “Ethylene Oxide”, Ullmann’s Encyclopaedia of Industrial Chemistry, Vol 13, pp 559-554.

9 Ly MA, 2014, Evaluation of components for the heterologous expression of Mycobacterium chubuense NBB4 monoxygenases. Ph D thesis, University of Sydney.