Difference between revisions of "Team:Sydney Australia/Results"

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

[[File:sydney_exp_characterisation_etn.png | center | 400px | thumb | Experimental outline of the characterisation of EtnABCD under the control of LacI repressor protein as part of the ''lac'' operon.]] | [[File:sydney_exp_characterisation_etn.png | center | 400px | thumb | Experimental outline of the characterisation of EtnABCD under the control of LacI repressor protein as part of the ''lac'' operon.]] | ||

| − | |||

The etnABCD genes were cloned from pSB1C3 into the broad host range vector pBBR1MCS-2, where they were expressed from the lac promoter, and electrotransformed into P. putida KT2440. Note that in the host that lacks LacI, the lac promoter is constitutive. The culture was exposed to ethene, but none of the expected product (ethene oxide) was formed, based on testing with the colorimetric NBP assay. In a similar experiment, the wild-type etnABCD genes cloned in the same plasmid yielded detectable ethene oxide, so all the experimental setup and reagents were working. | The etnABCD genes were cloned from pSB1C3 into the broad host range vector pBBR1MCS-2, where they were expressed from the lac promoter, and electrotransformed into P. putida KT2440. Note that in the host that lacks LacI, the lac promoter is constitutive. The culture was exposed to ethene, but none of the expected product (ethene oxide) was formed, based on testing with the colorimetric NBP assay. In a similar experiment, the wild-type etnABCD genes cloned in the same plasmid yielded detectable ethene oxide, so all the experimental setup and reagents were working. | ||

| Line 124: | Line 123: | ||

One reason for the ethene MO inactivity could be that our in-house harmonisation tool TransOpt did not yield a sequence which could be properly folded and active in ''Pseudomonas'', since this was the result unexpectedly obtained in parallel experiments with different codon-optimised forms of a fluorescent protein BsFP (outlined below). | One reason for the ethene MO inactivity could be that our in-house harmonisation tool TransOpt did not yield a sequence which could be properly folded and active in ''Pseudomonas'', since this was the result unexpectedly obtained in parallel experiments with different codon-optimised forms of a fluorescent protein BsFP (outlined below). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: theoretical_nbp.jpg | center | 400px | thumb | Expected results from the NBP assay. The assay results in a qualitative purple colour in the presence of epoxides (as indicated in tubes 2 and 4), with quantitative analysis enabled by spectrophotometric measurement of the solution. Credit to Samantha Chung]] | ||

<h4> Purpose </h4> | <h4> Purpose </h4> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:33, 13 October 2015

Results Overview

Aim

We aimed to express the enzyme ethene monoxygenase enzyme in Pseudominas Putida and show the oxidation of ethylene to ethylene oxide. This was done by:

- Codon Harmonisation (using our inhouse algorithm TransOpt) of Mycobacterium chubuense ethene MO (EtnABCD, or ethene MO) for Pseudomonas putida

- Expression of EtnABCD in P. putida

- Co-expression of E.coli GroEL-GroES to enhance folding to ensure highest possible activity

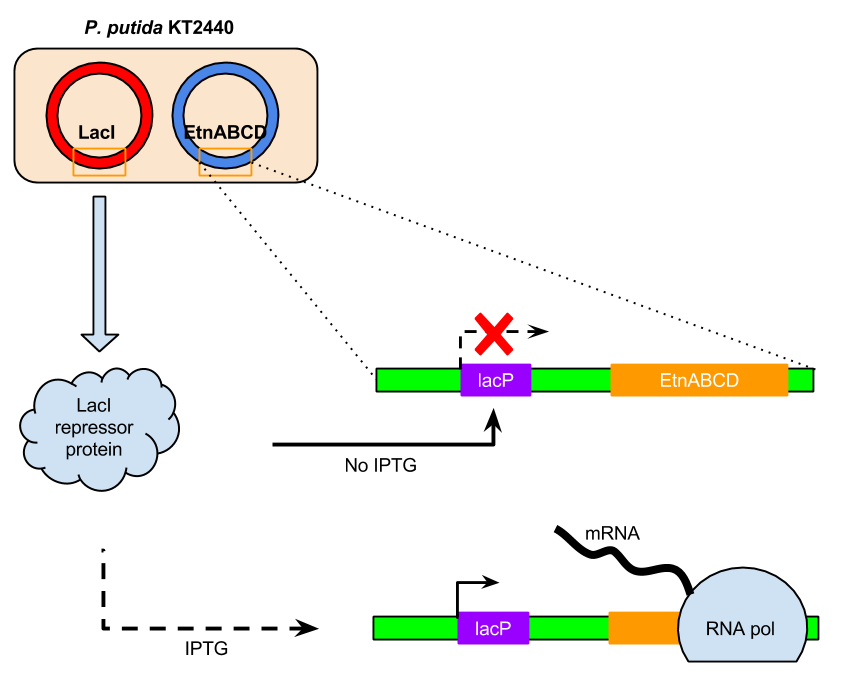

- Co-expression of LacI (LacI with constitutive promoter PLacIQ1) to control EtnABCD expression in P.putida

- Experimental validation of TransOpt via fluorescence assays using Bacillus subtilis fluorescent protein (BsFP)

Experimental design

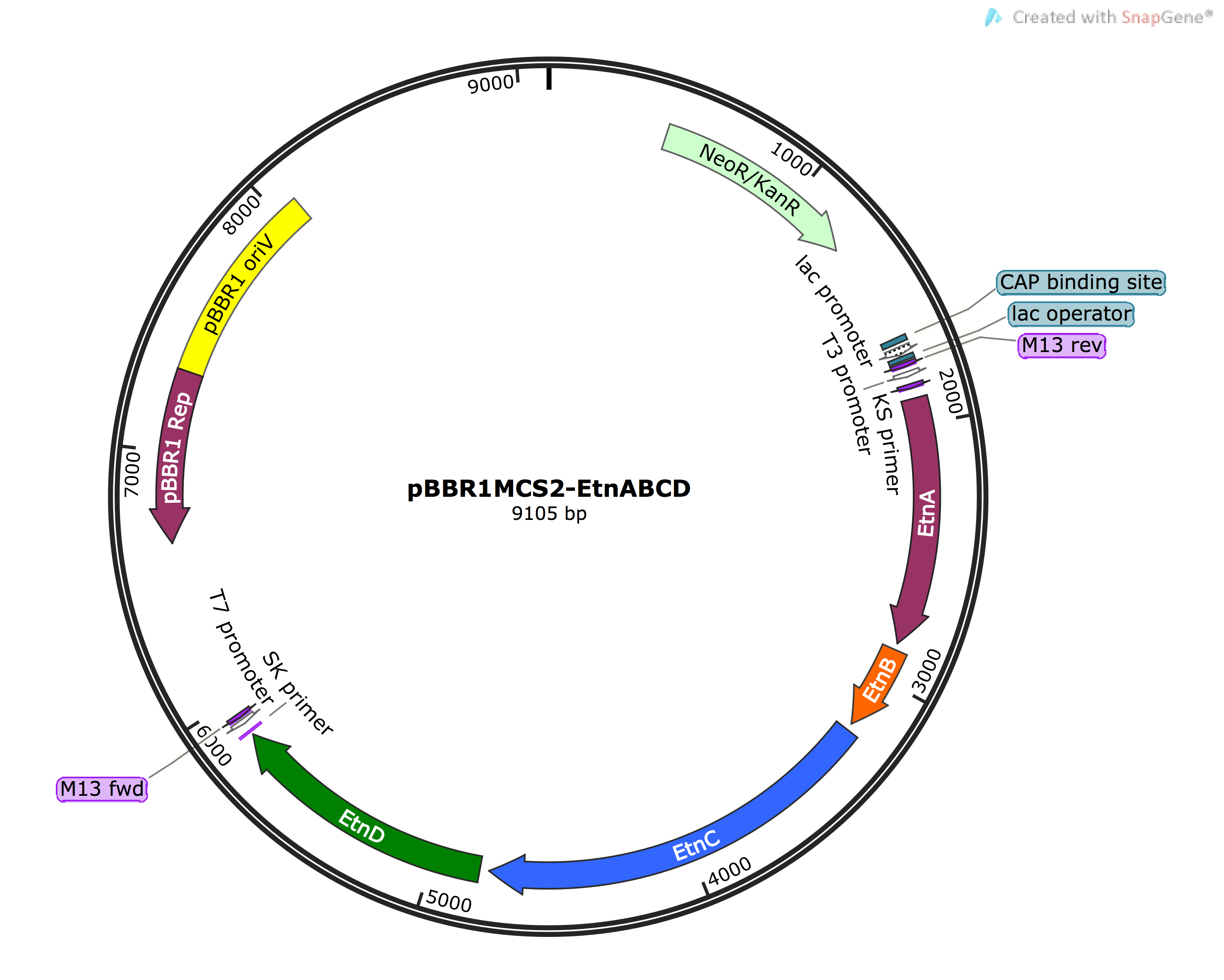

- Cloning EtnABCD Gblocks into pBBRMCS2 vector via Golden Gate Assembly and digestion/ligation

- Cloning GroEL-GroES into pUCP24 vector via PCR amplification from E.coli genome and digestion/ligation

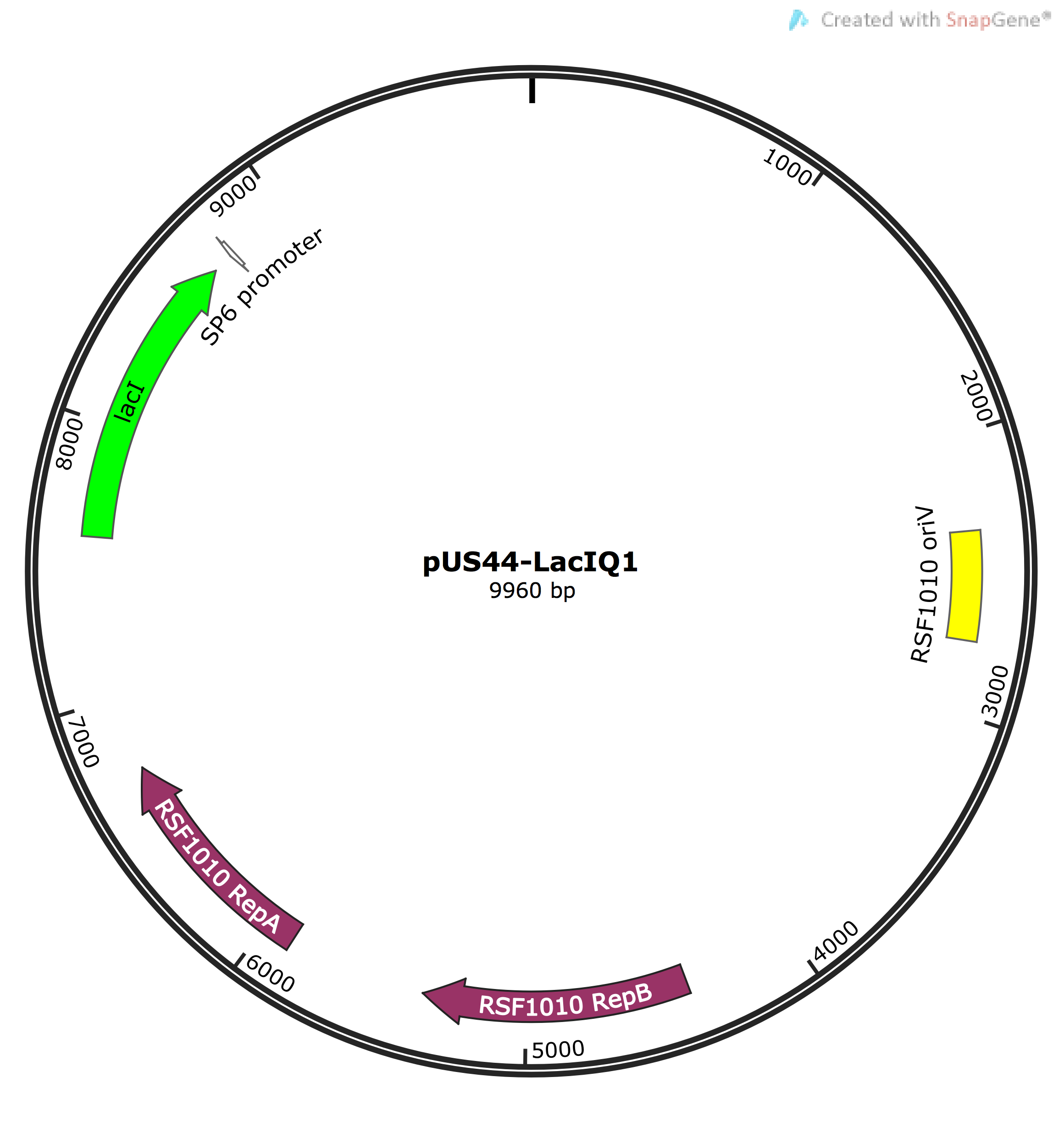

- Cloning LacI-PLacIQ1 into pSB1C3 (note that it carries its own promoter) via PCR amplification and digestion/ligation

- Cloning LacI-PLacIQ1 into pUS44 vector for co-expression with EtnABCD (note that pUS44 has different selectable marker so makes screening for presence of both EtnABCD and LacI easier)

- Inducing EtnABCD expression in P. putida with IPTG

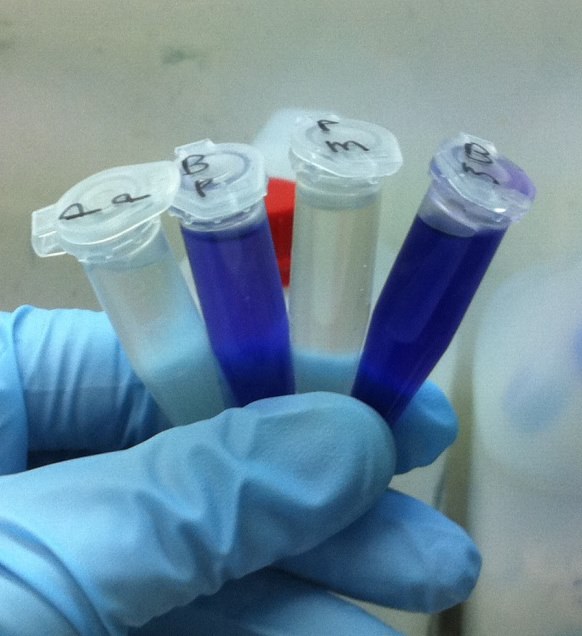

- Assessing if EtnABCD was functional and producing ethylene oxide via a Nito-benzyl-pyridine (NBP) colourimetric assay to detect ethene oxide

Summarised results

- NBP assay was not successful in detecting ethene oxide after induction of P.putida bearing LacI and EtnABCD, which shows that the enzyme does not work as expected

- LacIQ15 partially inhibited lac promoter activity in the absence of IPTG

- Fluorescence assay of BsFP showed that protein from standard harmonised algorithm had higher fluorescence than the TransOpt generated, indicating future work is required on the TransOpt algorithm

What did we find?

- Unable to make functional heterologous expression of EtnABCD in P.putida

- Characterisation of LacI and PLacIQ1 constitutive promoter functionality in regulating the lac operon

- TransOpt did not successfully optimise heterologous translation and folding, whilst standard harmonisation did

Full Results

... for the keen beans out there.I. LacI Characterisation

Experiment

LacI-PLacIQ1 consisting of LacI represser gene (from the lac operon system) and PLacIQ1 promoter upstream of the gene were PCR amplified from the pET15B vector using primers bearing cut sites including SalI, EcoRI and PstI for ligation into pUS44 and pSB1C3 vectors. After PCR clean up using Qiagen PCR kit, we performed digestion and ligation (as prescribed in the protocols page) to generate pSB1C3-LacI-PLacIQ1 (pSB-LacI) plasmid and transformed it into P. putida KT2440 cells followed by screening using chloramphenicol (Cm25) plates. Then, we set up patch colony plates and performed colony PCR screening using Taq polymerase to pick colonies bearing the correct pSB-LacI vectors. To further clarify the PCR results, we also performed a single digest to infer the presence of LacI in the final vector by the total fragment size.

Characterisation

To characterise the LacI repressor gene, we made E.coli JM109 competent cells with the pBBRMCS2 vector containing the LacZ-alpha gene. Then, we transformed the cells with LacI-pSB and incubated them over the following media to test the interactions between lacI and PLacIQ1 in this system. These media were:

- LB-Cm-Km-Xgal (repressed, expect white colonies due to lack of IPTG)

- LB-Cm-Km-Xgal-glucose (strongly repressed, expect white colonies due to lack of IPTG and presence of glucose)

- LB-Cm-Km-Xgal-IPTG (induced, expect blue colonies due to presence of IPTG)

- LB-Km-Xgal-IPTG (strongly induced, expect blue colonies due to presence of IPTG and loss of plasmid carrying lacI repressor gene)

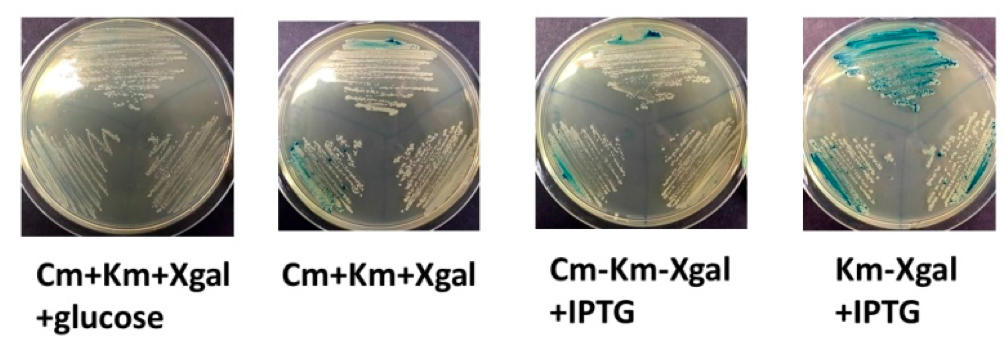

The results of this experiment were not entirely conclusive (above). Cells grown on LB-Cm-Km-Xgal-glucose were white, as expected, and cells grown on LB-Km-Xgal-IPTG were predominantly blue, as expected, but the other two media yielded a mix of white and blue cells, mostly white. It was notable that addition of IPTG was not sufficient to give uniform positive induction of lacZ. Our interpretation is that in this experimental setup, LacI repression is exceedingly strong. We believe this is because the amount of LacI protein expressed from the strong promoter on a high-copy plasmid will completely repress expression of the chromosomally-encoded omega fragment of LacZ, even when IPTG is present.

Purpose

The LacI-PLacIQ1 part was added to the project to tackle the issue of possible toxicity to the host cells due to overexpression of ethene monooxygenase, as a direct outcome from our HP work. From previous work, it was known that the enzyme is difficult to clone and express in heterologous hosts. Consquently, given primary cloning vector (pBBR1MCS-2) only had the Plac promoter but no LacI repressor, we needed to add the latter part separately. This added a second level of necessary control over the expression of ethene MO.

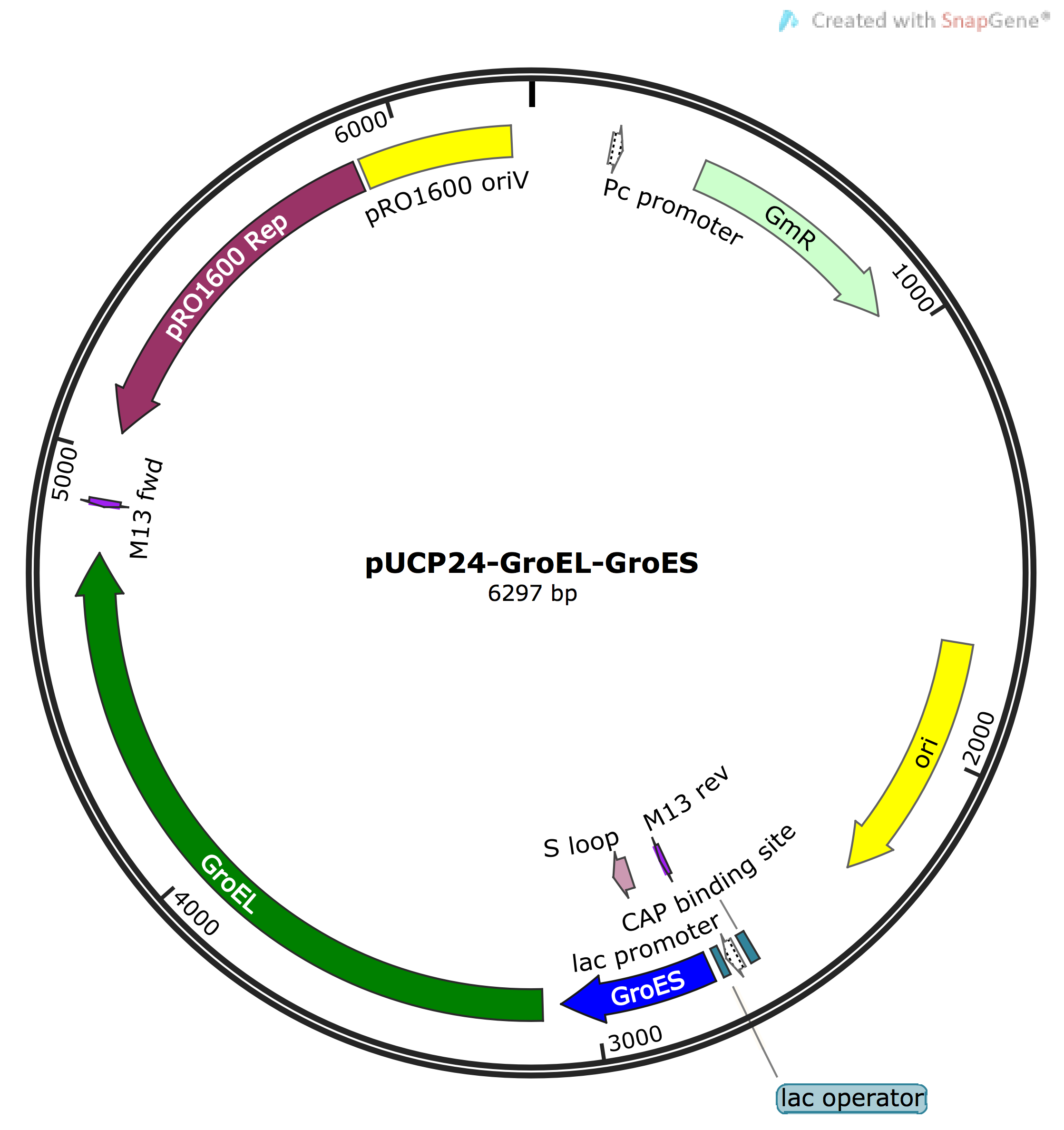

II. GroEL-GroES

Experiment

GroEL-GroES (GroES) experimental procedure evolved into two different phases due to the unsatisfactory results obtained from phase I necessitating the design of a second approach.

Phase I

We started by PCR amplifying the two Glocks containing P. putida GroES open reading frames (ORF). After several attempts, we managed to amplify the Gblocks and used them in the Golden Gate cloning reaction with digested PCR linearised pSB1C3 vector (PCR linearised pSB1C3 primers were designed so as not to amplify the RFP and are more suitable for ligation reactions). To screen for successful clones, we transformed the ligation mix into E. coli JM109 cells on agar plates containing chloramphenicol (Cm). After an overnight incubation, the colonies were patched and screened via PCR colony with primer designed to amplify the GroES-pSB1C3 (Gro-pSB) junctions. The clones showing the correct bands for the junctions were grown, and after miniprep, the plasmid was undergone a single and a double digest to check for the presence of the correct insert based on their size after running on agarose electrophoresis. Unfortunately, the digestion analysis gave negative results for all clones, with unexpected band sizes uncharacteristic of the anticipated 2 kbp of GroES.

Phase II

The absence of success in phase I contrived us to try a 'plan B'. In this phase, we amplified the E. coli GroES gene from its chromosomal DNA by PCR, with the primer containing the appropriate cut sites for cloning into pUCP24 vector (note: this E.coli GroES cannot be submitted as a part hence it was not cloned into pSB1C3). Then, using a simple digestion and ligation reaction, pUCP24-GroES (pUC-Gro) recombinant vector was constructed and screened via transformation into JM109 cells in media containing gentamicin (Gm). Clones were obtained, however, due to change in the course of project approach and design, this construct was not further analysed to confirm correct ligation.

Characterisation

Unfortunately due to the nature of results, lack of time, and change in the overall method design of the project, GroES was not used and characterised. However, we hope future iGEM teams take up this challenge and contribute to the discussion regarding the idea that GroES co-expression in different clones enhances expression and activity of enzymes.

Purpose

Due to low ethene oxidation activity of P. putida containing the wild-type EtnABCD in the previous work, we believed that GroES might help with the folding and help increase its activity. This method follows our hypothesis that the low activity was due to incomplete folding into the native conformation. The decision to choose E. coli GroES rather than the initial P. putida was due to reports that the former functions acceptablly in P. putida 1. Hence, the decision was made to generate E. coli GroES which can also be used later in E.coli with EtnABCD.

III. EtnABCD Characterisation

This is the main part of our experiment.

Experiment

As mentioned in the project page and the above experiment, we addressed the problems in the previous work, GroES and other challenges by changing the following in our method:

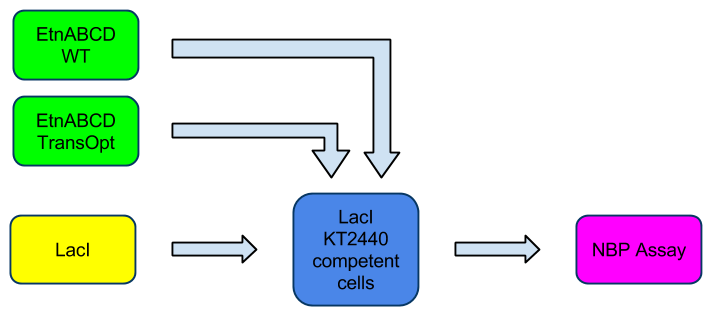

- Generation of a new harmonised EtnABCD sequence using TransOpt algorithm appropriate and optimised for expression in P.putida

- Co-expression of LacI repressor protein to control the expression of ethene MO as it is under the control of lac promoter (all part of lac operon gene regulatory system)

After running the Golden Gate reaction containing the three G-blocks and digested PCR linearised pSB1C3, followed by transformation into JM109 E. coli and selection on Cm selection plates, we screened the colonies by inoculating them in LB with Cm, performing miniprep and digestion analysis. The two digestion reactions (double and single) were conducted followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The clones showing the right bands (one large band and two bands in each reaction in single and double digests, respectively) were used to construct pBBRMCS2-EtnABCD (pBBR-Etn) plasmid. The pSB1C3-EtnABCD (pSB-Etn) vector was digested and ligated with digested pBBR vector. After transformation into P.putida KT2440 strain by electroporation and screening over kanamycin (Kan) plates, the clones were screened via colony PCR. The clones showing results that inferred the presence of Etn in pBBR vector were electrotransformed into P.putida KT2440 competent cells. The transformed competent KT2440 cells were incubated to express ethene MO (constitutively due to the 'leakiness' of lac promoter) and exposed to ethene to check for activity by screening for the presence of ethene oxide. The screening is performed via NBP assay which turns purple upon the presence of ethane oxide.

To add the extra level of control of ethene MO expression, the co-expression of LacI alongside ethene MO was also performed.

Characterisation

The etnABCD genes were cloned from pSB1C3 into the broad host range vector pBBR1MCS-2, where they were expressed from the lac promoter, and electrotransformed into P. putida KT2440. Note that in the host that lacks LacI, the lac promoter is constitutive. The culture was exposed to ethene, but none of the expected product (ethene oxide) was formed, based on testing with the colorimetric NBP assay. In a similar experiment, the wild-type etnABCD genes cloned in the same plasmid yielded detectable ethene oxide, so all the experimental setup and reagents were working.

We believed that the constitutive expression of ethene MO directly after transformation would put too much stress on the cells, resulting in the growth of deletion mutants or other unexpected incorrect plasmid derivatives. Hence, we introduced LacI to control the expression of the system on a second plasmid, an RSF1010 derivative called pUS44, and reintroduced the pBR1MCS-2/etnABCD ligation mixture. However, after IPTG induction, the NBP assay still failed to detect ethene oxide, which suggests that the inactivity lies within the enzyme itself, not the cells. Testing the assay reagents with a pure epoxide solution (styrene oxide) yielded a strong purple colour, which confirmed our suspicion that the EtnABCD enzyme itself was to blame.

One reason for the ethene MO inactivity could be that our in-house harmonisation tool TransOpt did not yield a sequence which could be properly folded and active in Pseudomonas, since this was the result unexpectedly obtained in parallel experiments with different codon-optimised forms of a fluorescent protein BsFP (outlined below).

Purpose

The motivation for the use of Golden Gate cloning method is outlined in the Golden Gate information page. Furthermore, the use of weaker ribosomal binding sites (RBS) upstream of each ORF and harmonisation of ethene MO sequence all aid the efficient translation and folding of the enzyme into its native conformation. Codon harmonisation ensures that the ribosome translation kinetics over ethene MO are conserved, as it affects protein folding, while weaker RBS ensures the inhibition of ribosomal traffic on the mRNA which can adversely affect mRNA translation and protein folding. It is also explained above why the LacI system was introduced into the P. putida expression of ethene MO.

TransOpt: Experimental Validation

In order to assess the performance of our novel codon optimisation algorithm we performed an experimental test to investigate its capability to generate a functional mRNA sequence that yields well-folded and highly functional proteins. Though we used this same algorithm to generate an optimised sequence for ethene MO in the target host p.putida (to preserve the translational kinetics profile of the ethene MO mRNA between the native and heterologous host), we saw it appropriate to perform a more simple and targeted validation test, via which we could assess other assumptions made in our work. This is because ethene MO would be too complex a protein for us to (on a single-case basis) reliably analyse and draw conclusions regarding the performance of the algorithm, as there are too great a number of contributing variables to the activity of the enzyme. Hence, we decided to use fluorescent protein as the target of our algorithm. Fluorescent proteins, such as GFP, are used widely in the literature as proteins to test the viability of codon optimisation algorithms (as discussed on the TransOpt page), with the major assumption being that the level of fluorescence is proportional to the efficacy of protein production and folding into the native conformation.

In our study, the b. subtillis flavin-binding fluorescent protein (BsFP) was used as a marker to test the validity of the different methods for codon optimisation. The particular protein (BsFP) is a promising new alternative to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) family of proteins: BsFP is a small protein (137 amino acids), it is functional in many different cellular environments and has high tolerance to changes in pH, oxygen levels and heat, making it applicable to a wide range of experiments. In contrast, GFP is much larger, matures slowly, absolutely requires oxygen for fluorescence, and is sensitive to chemical changes 1. Furthermore, in the context of our planned experiments, the lack of genome sequence for the GFP source organism aequorea victoria means that no tRNA GCN profile is available, which is crucial for the newly-developed harmonisation algorithm. However, the choice of this fluorescent protein does present downsides: It may not include complex folding domains, the presence of which motivated TransOpt's designed capability for regulating translation rate trends. Furthermore, fluorescent markers were the prototypical proteins upon which many of the existing codon optimisation methods have been developed, and so it would not be surprising if standard optimisation methods succeed here, though they may fail on more complex sequences (see Scientific Background of TransOpt). Thus, without a complex folding structure, the benefits afforded by TransOpt might be minimal (for example, in comparison to standard codon harmonisation algorithms).

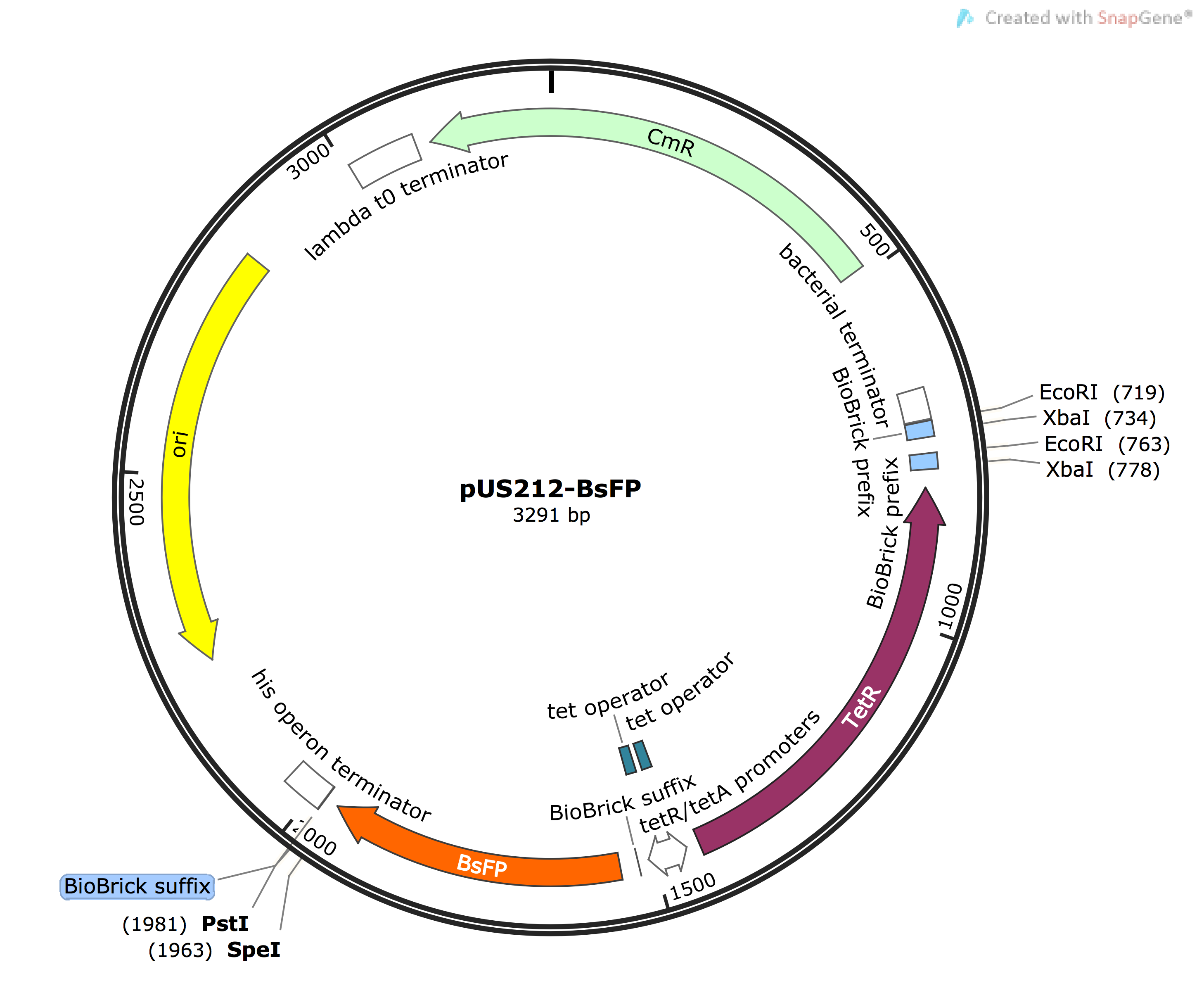

The following four BsFP sequences were generated, cloned in to pUS212 vector and induced in tetracycline (TetR) - in low amounts that do not exhibit antibiotic properties - and induced in e.coli to verify the algorithm. We generated all sequences ourselves, as described on the TransOpt page, using a rate quantisation methodology based on the organisms' tRNA Gene Copy Numbers.

- BsFP-WT: native sequence from the native host B. subtilis

- BsFP-fast: all codons were replaced with the E.coli versions that possessed the fastest translation rate, as quantised using the approach of Spencer et al 3

- BsFP-standard: harmonised BsFP generated via standard harmonisation (as proposed by Angov et al 1) using the rate quantisation approach of Spencer et al 3

- BsFP-TransOpt: optimised BsFP sequence generated using our new TransOpt algorithm

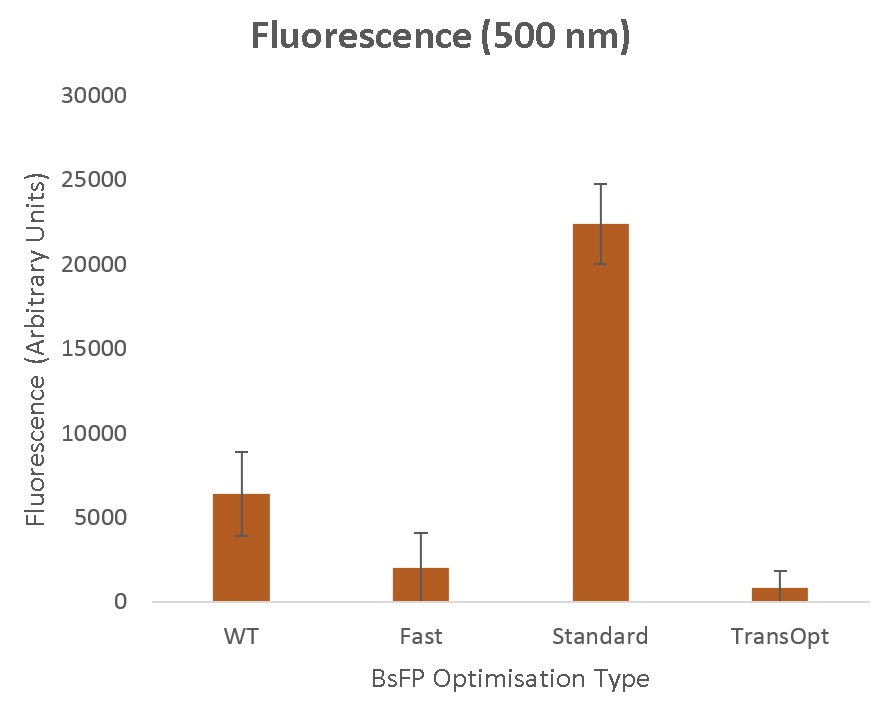

By measuring changes in fluorescence, the folding of the protein can be determined. We expect that high fluorescence will be detected from the standard harmonised variant (as demonstrated by past studies), but we hope that the TransOpt variant's fluorescence will be better still, due to superior folding than the other variants. We expect the fast optimised sequence will demonstrate a decreased fluorescence compared to the wild type, as these rate-maximisation approaches to optimisation have been shown to be flawed in past studies (see discussion on the TransOpt page).

Method

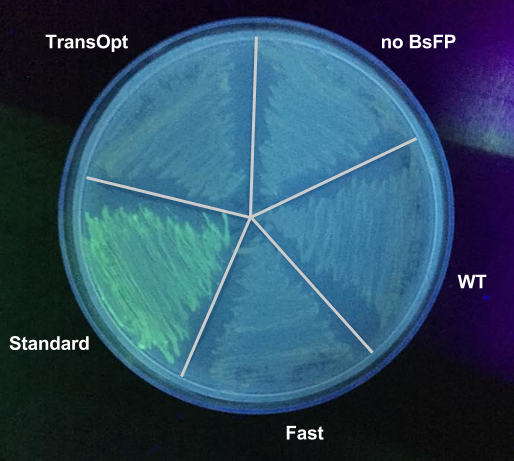

All four BsFP GBlocks were designed to have the BioBrick prefix and suffix at either ends. Firstly, BsFP was cloned into pUS212 expression vector via digestion/ligation. To screen for the recombinant vector, the ligation mix was transformed into JM109 E.coli and screened over agar LB plates containing chloramphenicol (Cm). Then, the colonies were used for colony PCR to check for the presence of the ligated insert and subsequently patched on a new plate with TetR (100 ng/uL) to induce BsFP expression. To gain an immediate qualitative data of the induced patch colonies, they were exposed to wide range UV light and screened for presence of green fluorescent colonies. Using this knowledge and the PCR colony results after running agarose gel electrophoresis, an equal number of appropriate colonies of each BsFP variant was picked, inoculated, and induced in LB broth containing Cm and TetR (TetR is added after the culture reaches the appropriate OD600. Finally, four hours after the addition of the inducer, the samples were taken and had their OD600 and fluorescence measured with excitation at 460 nm and emission at 500-520 nm, with controls such as GFP and empty pUS212 vector containing no BsFP gene. To normalise the data, the fluorescence arbitrary unit/OD600 (Flou/OD) of the empty pUS212 containing colonies was subtracted from each BsFP variants' Flou/OD.

To develop the pSB1C3-BsFP plasmid, BsFP Gblock was digested/ligated, transformed and screened by Cm, colony PCR and sequencing.

Results Summary

Our raw results are in the figure below, demonstrating that the standard codon harmonisation method and the fast-codon optimised method performed as expected when compared to the wild type. However, the TransOpt method did not function as desired, producing levels of fluorescence indistinguishable (to within experimental error margins) from those in the control case. Aside from the distinct possibility of errors in the experimental procedure used to prepare this variant for measurement, a number of sequence-based causes may have been responsible for this negative result, as discussed on the TransOpt Experimental Validation page.

In conclusion, we were able to achieve the following aims:

- Demonstrated that the sequence generated via the standard codon harmonisation algorithm was able to give improved fluorescence, supporting the rate quantisation methodology we have employed.

- Demonstrated that the sequence generated via selecting fast-translating codons results in decreased fluorescence, supporting our hypothesis that the use of only fast-translating codons may result in slowed (and possibly stalled) translation.

However, we came short of reaching the following aim:

- Demonstrate that TransOpt improves upon the standard codon harmonisation method.

For full analysis of these results, discussion of their implications for the effectiveness of our algorithm, and identification of potential avenues for future improvement, please see the TransOpt page.

References

1 Venturi V et al. Amplification of the groESL operon in Pseudomonas putida increases siderophore gene promoter activity. Mol Gen Genet. 1994 Oct 17;245(1):126-32.

2 Mukherjee, A., et al., Characterization of flavin-based fluorescent proteins: an emerging class of fluorescent reporters. PLoS One, 2013. 8(5): p. e64753.

3 Spencer P et al., 2012, “Silent Substitutions Predictably Alter Translation Elongation Rates and Protein Folding Efficiencies”, Vol 422, pp. 328-335.