Difference between revisions of "Team:Austin UTexas/Project/Caffeine"

Kvasudevan (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

=== Background === | === Background === | ||

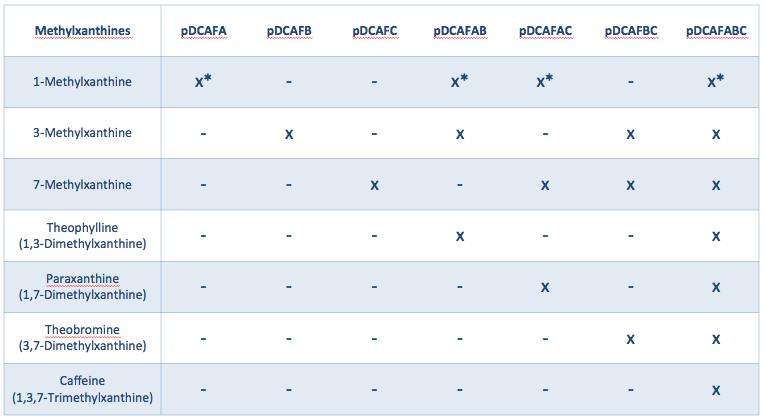

| − | [[Image:UT_Austin_2015_Table_Methylxanthines.png|500px|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:UT_Austin_2015_Table_Methylxanthines.png|500px|thumb|right|<b>Fig.1:</b> Different plasmid constructs matched with what methylxanthines they are capable of degrading.]]The 2012 UT Austin iGEM team created the pDCAF3 plasmid which, when transformed into the ∆guaB strain of E. coli, allowed the team to accurately measure the amount of caffeine in a drink. The pDCAF3 plasmid allows ΔguaB E. coli to demethylate caffeine and other methylxantines to make xanthine, a precursor and suitable replacement for guanine. |

| − | While this works well for solutions that only contain caffeine | + | The ∆guaB strain has the guaB gene knocked out, which is a crucial step in the biosynthesis of guanine. However, if the ∆guaB strain is given the pDCAF3 plasmid, it is able to bypass the need for the enzyme encoded by guaB and make guanine given environmental methyxanthines. Thus, by measuring the growth of the ∆guaB E. coli with pDCAF3 plasmid in a solution containing caffeine and comparing to a growth curve, we can correctly estimate the amount of caffeine. |

| + | |||

| + | While this works well for solutions that only contain caffeine, the ΔguaB pDCAF3 bacteria will grow in the presence of any methylxanthine, xanthine,or guanine. Many of these are present in drinks made from organic products, such as coffee or tea, where knowing the exact amount of caffeine would be helpful. Thus, our goal this summer was to create a set of plasmids based on the pDCAF3 plasmid that will allow us to subtract out the background growth from those non-caffeine molecules. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The pDCAF3 plasmid contains five genes that allows it to demethylate caffeine: three (ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC) that specifically demethylate each of the three methyl groups, and two (ndmD and gst9) that are necessary for the other three to work, but don’t contribute directly to the demethylation. We decided to create a set of seven plasmids that all contain ndmD and gst9, and either contain one of the other three, a pair of the other three, or all of the other three genes (<b>Figure 1</b>). Without all three of ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC, the bacteria will only be able to degrade some methylxanthines, not all of them, and only having all three will allow them to degrade caffeine specifically. By growing ∆guaB strains that contain each of these plasmids with a single sample of coffee, tea, or other drink that contains multiple methylxanthines, we can subtract out the growth based on the non-caffeine molecules from the strain that can degrade caffeine and get a much more accurate measurement of the amount of caffeine in the sample. | ||

[[Image:2015_Austin_UTexas_pDCAFplasmid_design-AG.png|400px|thumb|left|'''Fig. 2:''' Design for set of plasmids derived from pDCAF3. Each plasmid contains a different subset of ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC. The most highly methylated methylxanthine (with the methyl groups removed by the plasmid) are pictured inside each plasmid. On the left is the pDCAF3 plasmid design with the genes labeled.]] | [[Image:2015_Austin_UTexas_pDCAFplasmid_design-AG.png|400px|thumb|left|'''Fig. 2:''' Design for set of plasmids derived from pDCAF3. Each plasmid contains a different subset of ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC. The most highly methylated methylxanthine (with the methyl groups removed by the plasmid) are pictured inside each plasmid. On the left is the pDCAF3 plasmid design with the genes labeled.]] | ||

Revision as of 19:50, 18 September 2015

Background

The ∆guaB strain has the guaB gene knocked out, which is a crucial step in the biosynthesis of guanine. However, if the ∆guaB strain is given the pDCAF3 plasmid, it is able to bypass the need for the enzyme encoded by guaB and make guanine given environmental methyxanthines. Thus, by measuring the growth of the ∆guaB E. coli with pDCAF3 plasmid in a solution containing caffeine and comparing to a growth curve, we can correctly estimate the amount of caffeine.

While this works well for solutions that only contain caffeine, the ΔguaB pDCAF3 bacteria will grow in the presence of any methylxanthine, xanthine,or guanine. Many of these are present in drinks made from organic products, such as coffee or tea, where knowing the exact amount of caffeine would be helpful. Thus, our goal this summer was to create a set of plasmids based on the pDCAF3 plasmid that will allow us to subtract out the background growth from those non-caffeine molecules.

The pDCAF3 plasmid contains five genes that allows it to demethylate caffeine: three (ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC) that specifically demethylate each of the three methyl groups, and two (ndmD and gst9) that are necessary for the other three to work, but don’t contribute directly to the demethylation. We decided to create a set of seven plasmids that all contain ndmD and gst9, and either contain one of the other three, a pair of the other three, or all of the other three genes (Figure 1). Without all three of ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC, the bacteria will only be able to degrade some methylxanthines, not all of them, and only having all three will allow them to degrade caffeine specifically. By growing ∆guaB strains that contain each of these plasmids with a single sample of coffee, tea, or other drink that contains multiple methylxanthines, we can subtract out the growth based on the non-caffeine molecules from the strain that can degrade caffeine and get a much more accurate measurement of the amount of caffeine in the sample.

Plasmid Design

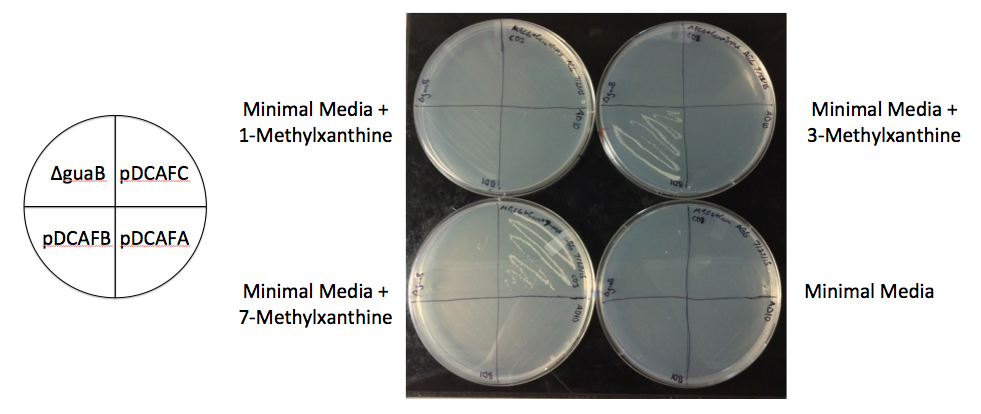

We created a set of seven plasmids containing subsets of the ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC genes that should each grow on a different subset of methylxanthines (Fig. 1, 2). The plasmids were named based on the pDCAF3 naming scheme and which subset of genes it contains (e.g. pDCAFC contains ndmC, ndmD, and gst9, while pDCAFAC contains those along with ndmA). In addition, each gene was giving a different RBS (see Increased Stability below). The different genes were amplified from the pDCAF3 plasmid and cloned using the BioBrick Standard Assembly method. Once each plasmid was complete, it was transformed into ∆guaB E. coli and grown on minimal media supplemented with the most methylated methylxanthine it can degrade in order to prevent the genes from breaking.

Detection of Caffeine and Related Molecules

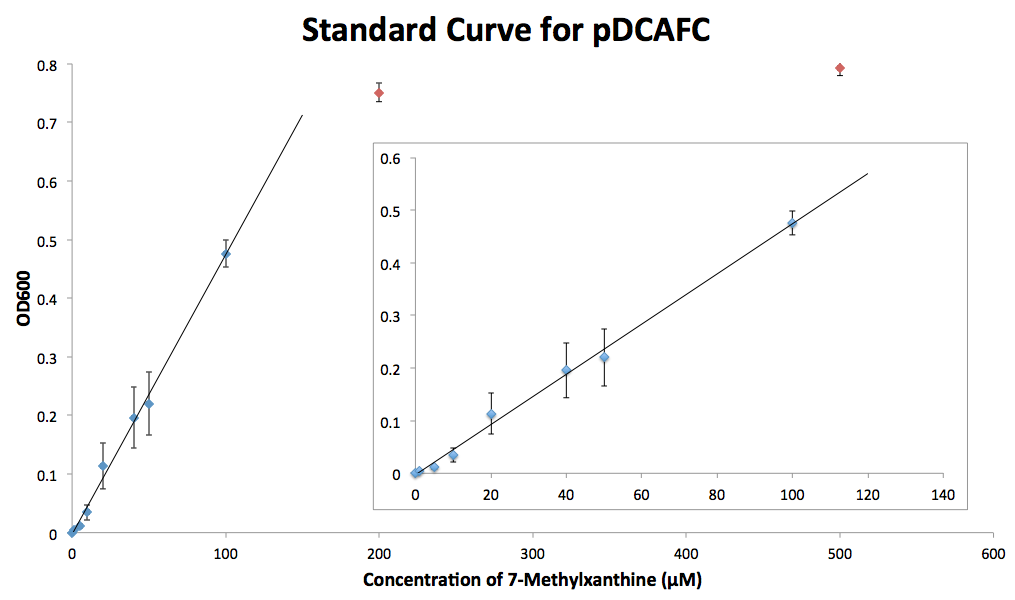

This set of plasmids can be used to measure the concentration of methylxanthines in solutions, even caffeinated beverages like coffee or tea that have a mixture of methylxanthines. In order to do so, we first had to create standard growth curves of the strains of ∆guaB E. coli containing the different plasmids. We grew each strain in triplicate in minimal media cultures containing different concentrations of the methylxanthine they degrade. These cultures were grown overnight and measured for OD600 the next day. The results were graphed against the concentration of methylxanthine in the media, and a linear fit was made for the cultures that did not grow to saturation, with the cutoff being around 200 µM (Fig. 4).

Increased Stability

In addition to creating the six plasmids with combinations of genes that did not exist before, we also redesigned the original pDCAF3 plasmid for greater stability. The pDCAF3 plasmid contained a synthetic operon with the five demethylation genes under the control of one promoter. However, four of the five genes contained the same RBS and surrounding sequence, meaning that there is a 25 bp sequence of DNA that is repeated four times in the sequence. This repeated sequence introduces a risk of repeat-mediated deletion, making the plasmid more unstable than it needs to be. As such, during the cloning process we changed the RBS sequences for each of the genes so that they would stay within an order of magnitude in strength, but would have a different enough sequence to alleviate the chances of repeat-mediated deletions, making the entire plasmid more stable while retaining the same functionality.

References

Quandt, Erik M., et al. "Decaffeination and measurement of caffeine content by addicted Escherichia coli with a refactored N-demethylation operon from Pseudomonas putida CBB5." ACS synthetic biology 2.6 (2013): 301-307.

Summers, Ryan M., et al. "Novel, highly specific N-demethylases enable bacteria to live on caffeine and related purine alkaloids." Journal of Bacteriology 194(8) (2012): 2041-2049.