Team:TAS Taipei/wetlab

Experimental

Full Granzyme B (GzmB) Inhibitor Device

The main component of our device design (Figure 1) codes for a protein (Antichymotrypsin with three amino acid mutations, which we refer to as ACT3m) that can specifically inhibit extracellular GzmB activity. Attached to ACT3m is YebF (isolated from BBa_K1510009), an E. coli motor protein that secretes proteins fused to it through the bacterial cell membrane. Expression of the protein is controlled by a temperature-sensitive promoter (BBa_K608351). This promoter is the primary regulator, and does so by initiating transcription at or above 37⁰C. Finally, we included a strong ribosome binding site (RBS; BBa_B0034) for translation, and a double terminator to end transcription (BBa_B0015).

Granzyme B Inhibitor (ACT3m)

Our goal is to prevent damage from excess degradation of ECM proteins in chronic inflammatory conditions. To protect ECM proteins from cleavage by GzmB without interfering with GzmB's intracellular functions, we wanted to find an inhibitor that could function exclusively in the extracellular space. Through literature research, we found that the GzmB inhibitor in humans is called SerpinB9, but it functions mainly inside cells (Sipione et al., 2006). In mice, an extracellular inhibitor, Serpina3n, exists (Ang et al., 2011). However, we wanted to inhibit GzmB in the human body, so we knew we had to find an inhibitor that would work in humans. Finally, we came across a paper where mutations made to an extracellular human protein, Antichymotrypsin (ACT), allowed it to bind and inhibit GzmB (Marcet-Palacios et al., 2014). This was perfect for our purposes, so we ordered ACT cDNA (from Sino Biological Inc.) and followed their method to create an extracellular human GzmB inhibitor.

Removing P (PstI) Sites

Upon receiving the ACT gene and analyzing the provided sequence, we learned that there are two P cutting sites in the gene sequence. These two P sites would interfere with cloning, especially since P is an essential site in the BioBrick backbones that we want to build. To remove these internal P sites, we sent the part to a company (Mission Biotech) for mutagenesis. The nucleotide sequence was mutated to remove the P sites, without changing the final amino acid sequence. A sequence was provided at the end for confirmation.

Changing Three Amino Acids

Naturally, ACT is an extracellular protein found in humans. This makes it a good starting point, because it is location-specific; however, ACT lacks the ability to bind and inhibit GzmB. The authors of the paper (Marcet-Palacios et al., 2014) compared the amino acid sequence between the extracellular mouse inhibitor Serpina3n and human ACT, and identified three amino acids that would transform ACT into a GzmB-binding protein (Figure 2). They found that these mutations successfully retained the extracellular nature of ACT, while allowing it to bind and inhibit GzmB. To follow their protocol and perform the same mutations, we again sent the part out for mutagenesis (Mission Biotech). We confirmed the mutated sequence (sequenced by Tri-I Biotech).

Assembly into a BioBrick Backbone

Next, to insert this part in front of a double terminator (BBa_B0015), we designed primers to add on the BioBrick prefix (including E and X sites) and suffix (including S and P sites) to either side of ACT3m. The primer designs were sent to Tri-I Biotech for oligo synthesis, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was set up.

Motor Protein (YebF)

We wanted our chassis (E. coli) to express and secrete the desired inhibitor so it can be used as part of our topical prototype. For this reason, we inserted YebF in front of ACT3m. YebF is a motor protein that can secrete attached proteins out of the E. coli membrane. Thus, in our final construct, the resulting YebF-ACT3m fusion protein can be separated from the bacterial cells.

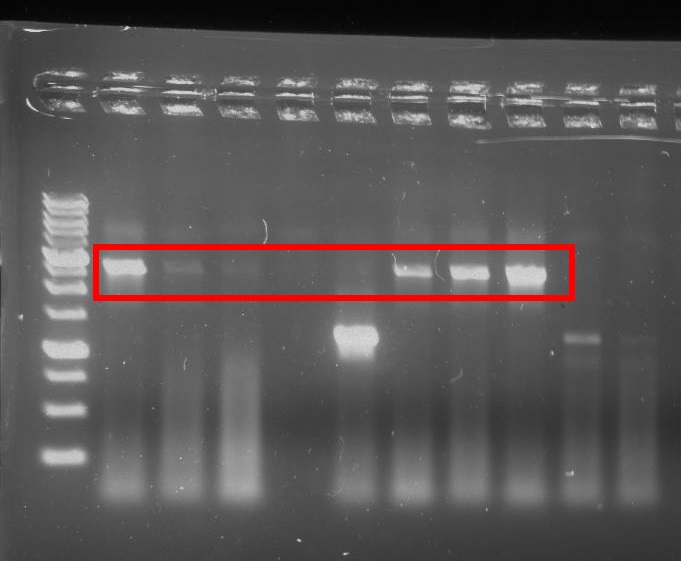

Assembly into Final Device

We asked the National Yang Ming University iGEM team (NYMU-Taipei) for a device containing YebF (BBa_K1510009) and received the part promptly. Since YebF was given to us on a composite part device, we also needed to design primers to add restrictive enzyme cutting sites. Following the same method used for ACT, we designed primers, which were synthesized by Tri-I Biotech, and performed PCR. Figure 3 shows YebF successfully inserted into a device behind our promoter (discussed below) and RBS.

Temperature-Sensitive (TempSens) Promoter

When chronic inflammation occurs, GzmB may be produced by a number of different cells (in additional to T cells and natural killer cells) (Boivin et al., 2009). This may contribute to the elevated levels of GzmB in inflammation. We wanted to avoid inhibiting all GzmB activity, since a normal level of GzmB is still an important part of the immune system. Our goal was to control the expression of our inhibitor protein, so that expression can be shut off when normal GzmB levels are reached (further discussed in Modeling). To achieve this, we looked for promoters in the iGEM parts registry that can be induced manually. We found a temperature-sensitive promoter (BBa_K608351), a composite part designed by iGEM11_Freiburg. We ordered this from the parts registry, and immediately began assembly and testing.

Assembly into Promoter-Testing Device

The first goal with the temperature-sensitive promoter was to confirm that it was functioning. In order to test the promoter’s activity, we designed a testing device with green fluorescent protein (GFP) as the reporter (Figure 4). We hypothesized that at lower temperatures the promoter should not initiate transcription; therefore, no GFP would be present. When exposed to higher temperatures, the promoter would then begin transcription and express the downstream GFP. As seen in Figure 5, we successfully inserted the temperature-sensitive promoter in front of a GFP generator (BBa_E0840).

Testing Activation Temperature

After successfully cloning in the temperature-sensitive promoter, we realized one immediate problem: the exact temperature of activation is unknown. In order to test this, we restreaked bacteria containing the promoter and GFP generator device onto several plates. These were incubated at different temperatures: 30⁰C, 32⁰C, 34⁰C, 35⁰C, 36⁰C, 37⁰C, and 42⁰C (Figure 6, some temperatures not shown). Bacteria successfully grew on all plates (Figure 6); however, under blue light conditions, it can be seen that only bacteria incubated at 37⁰C actually glowed (Figure 7). This is evidence that the temperature-sensitive promoter is only active at and above 37⁰C.

Testing Activation Time

After determining the activation temperature of the promoter, we also tested how long it takes for the promoter activation to be visually determined. Bacteria carrying the testing device were grown at a lower temperature (35⁰C), so that the promoter is not already active. The plates were then transferred to the activation temperature (37⁰C), and checked hourly until GFP was observed. After about 3 hours at 37⁰C, fluorescence was detected (Figure 8).

Assembly and Testing the Main Granzyme B Inhibitor Device

We successfully assembled and sequenced the full GzmB inhibitor device (Figure 9).

After completing our full device, and knowing that we cannot directly test the effects of ACT3m on human GzmB (we do not have the safety clearance to test human samples!), we wanted to see if our chassis was actually expressing the correct protein. We ran an SDS-PAGE gel using E. coli samples containing our full device (Figure 10).

We also ran a biuret protein color indicator test (Figure 11), which turns from blue to purple. The biuret solution turning purple indicates that proteins were secreted into the LB. The tube containing ACT3m only (without YebF) remained blue, which indicates that proteins were not found in the solution. Combined with our SDS-PAGE results, this indicates that the full device synthesized and secreted YebF+ACT3m out of the bacteria.

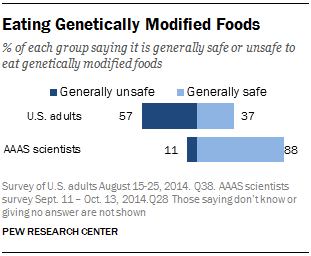

Functional Prototype

According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2014, 88% of scientists polled believe it is generally safe to eat genetically modified foods, compared to only 37% of U.S. adults (Figure 12; Funk & Rainie, 2015). There is a huge difference in opinion between scientists and the public. These results match a survey that we gave during our school's Spring Fair as well, where we found that over 52% of students polled are uncomfortable with genetically modified products. Given this information, we imagine that the public would be fearful of using biopharmaceuticals where living bacteria is used either in or on the body. We wanted to design the least invasive and most socially acceptable method of drug delivery: a topical solution where bacteria (our chassis) is prevented from entering into the body, and the only thing delivered is the GzmB inhibitor.

We envision two different drug delivery methods, for either localized or general treatment. Localized treatment focuses on topical delivery of our inhibitor ACT3m into targeted inflamed areas through a bandage (Figure 14). On the other hand, general treatment of the entire body can be achieved using a cream (containing our inhibitor; Figure 23).

Control of GzmB Inhibitor Device

Since we want to design topical prototypes for our drug delivery, we first needed to make sure that contact with skin doesn't directly activate our temperature-senstiive promoter. We still want to retain control of when to start expression of our GzmB inhibitor. The skin temperatures of different areas were measured using an infrared thermometer.

Average temperatures for different areas are shown in Figure 13. The overall average temperature is 33.35 ⁰C, which is safely below the activation temperature. These results demonstrate that contact with skin will not activate the device directly, and we can still control its expression by application of a heat pack.

Localized Treatment: Bandage

Our first prototype focuses on localized conditions (such as wounds), where a bandage may be applied to deliver our GzmB inhibitor. Because we want to keep bacteria outside of the human body, we needed to design a prototype that would retain bacteria inside our bandage (Figure 14).

We decided to use a semi-permeable membrane with pores small enough to retain the bacteria within our bandage, but large enough to allow proteins to diffuse through. Since the size of E. coli is 0.5µm x 2µm, we used a mixed cellulose ester membrane with pore sizes of 0.2µm. Bacteria can be grown on a thin LB agar contained between our semi-permeable membrane and an outer hydrocolloid covering (to keep bacteria from escaping on the other side). We have successfully built a functional prototype, and used different methods to test the effectiveness of both the semi-permeable membrane's ability to contain bacteria and allow proteins through.

Testing the Semi-Permeable Membrane

Prototype testing allows us to determine the viability of our theoretical drug delivery construct. First, we tested the ability of the semi-permeable membrane to sustain bacteria growth on LB agar, but prevent the bacteria from moving to the other side. We streaked out bacteria onto LB agar on one side of the membrane, and placed a clean LB agar on the other side (set up shown in Figure 15). After allowing growth overnight, we checked for the presence of bacteria on the clean LB agar. Two trials were done, and our results show no growth on the clean LB agar (one trial shown in Figure 16). This demonstrates that the 0.2µm cellulose ester membrane can be used to keep bacteria inside the bandage, so there is no direct contact with the skin.

A second test was carried out to independently test the semi-permeable membrane (Figure 17). Again, we found that the membrane was successful in preventing bacteria from moving across.

After showing that bacteria cannot pass through the membrane, we needed to test whether the proteins could actually move across the membrane. We placed our membrane in a Buchner funnel over a filter flask (Figure 18). Liquid cultures were prepared and pulled through the membrane using a vacuum. For our experiment, we set up 3 groups: (A) lysed cells releasing free GFP; (B) E. coli cells expressing GFP; (C) LB without bacterial cells. Each group was filtered through the 0.2 um pore membrane and the filtrate was collected. When the filtrate was exposed to blue light, only the group that contained lysed cells glowed (Figure 19). This shows that proteins passed through the membrane.

Building and Testing the Bandage Prototype

We built the entire bandage prototype, and found that the semi-permeable membrane used successfully keeps bacteria inside the bandage in our final product (Figure 20).

Microneedles

For conditions where inflamed sites are not directly exposed to the bandage, such as swollen joints in rheumatoid arthritis, microneedles may help delivery of ACT3m through the skin. Microneedles can create tiny channels in the epidermis (Prausnitz, 2004) so that our GzmB inhibitor can be delivered to deeper areas pass the skin (Figure 21).

General Application: Cream

In cases where chronically inflamed sites are not localized (such as in psoriasis, Figure 22), we envision a second prototype for general topical use. Our GzmB inhibitor protein (ACT3m) would be extracted from bacteria, purified, and put into a cream (Figure 23). One of the following methods might be used to deliver our protein through the skin.

Microneedles

Microneedles can create tiny channels in the epidermis (Prausnitz, 2004) to deliver our ACT3m protein in the cream through the skin. A microneedle roller can be used before applying the cream.

TD1

TD1 is a patented peptide (PP, et al. 2014) with the sequence ACSSSPHKHCG. When mixed with proteins, this peptide can carry proteins through the skin. To help transdermal ACT3m delivery, TD1 will be added into the cream.

Transfersomes

Transfersomes are specialized liposomes (made by a certain procedure) that can carry the encapsulated materials through the skin (Jain et al., 2003). ACT3m would be put into transfersomes, so that when the cream is applied, these transfersomes will bring our GzmB inhibitor through the skin.

Tocopheryl Phosphate Mixture (TPM)

Tocopheryl phosphate is a natural form of vitamin E, which, when mixed with proteins, increases their transdermal delivery (Cottrell, 2014). TPM was developed by Phosphagenics, an Australian biotechnology company. Using this technology, Phosphagenics developed an insulin cream, which is currently going through the FDA approval process (Segal & Michelson, 2015). If successful, this could also be used in our cream prototype to deliver ACT3m.

Safety Device

Our prototype (described above) is designed to contain bacteria within a bandage. However, accidents (almost always) happen. How can we make sure that bacteria do not escape into the environment? A safety device to ensure cell death outside of our bandage prototype.

There are two main components: a gene that encodes T4 Endolysin (BBa_K112806), which is controlled by a repressible promoter called pDapA (BBa_I718018). T4 Endolysin is an enzyme from the virus Enterobacteria phage T4 (Young, 1992). When expressed, T4 Endolysin can degrade peptidoglycans in bacterial cell walls, which kills the bacteria (Young, 1992). The promoter we use is pDapA, a constitutive promoter that can be repressed by diaminopimelic (DAP) acid.

Since pDapA is always unless at least 300µM DAP acid is present, we will add the DAP acid into the LB agar in our bandage prototype. This way, the E.coli bacteria do not die within the bandage. If they escape the bandage, however, as DAP acid is usually not found in the environment, pDapA will be activated (Acord and Masters, 2004) and expression of T4 Endolysin will kill the bacteria.

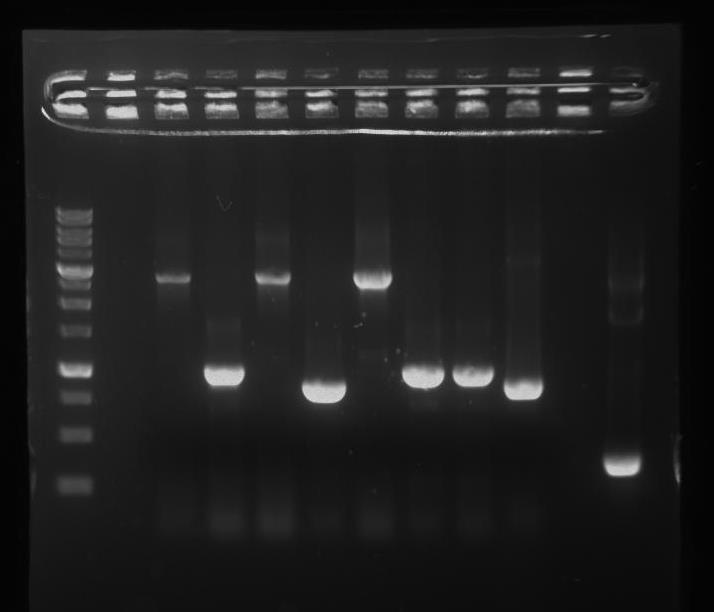

Assembly into Final Safety Device

First, we inserted a double terminator (BBa_B0015) behind T4 Endolysin, and the pDapA promoter before a strong RBS (BBa_B0034). Next, we wanted to assemble these parts together. Figure 25: shows a PCR gel check of the cloning products, where the correct PCR product is estimated to be ~1kb.

Our future plans include confirming whether we have the correct safety device through sequencing. We also want to test if the device works; if no DAP acid is present, the bacteria should die.

Citations

Sipione, S., Simmen, K., Lord, S., Motyka, B., Ewen, C., Shostak, I., . . . Bleackley, R. (2006). Identification of a Novel Human Granzyme B Inhibitor Secreted by Cultured Sertoli Cells. The Journal of Immunology, 5051-5058. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5051

Ang, L., Boivin, W., Williams, S., Zhao, H., Abraham, T., Carmine-Simmen, K., . . . Granville, D. (2011). Serpina3n attenuates granzyme B-mediated decorin cleavage and rupture in a murine model of aortic aneurysm. Cell Death & Disease, E209-E209. doi:10.1038/cddis.2011.88

Marcet-Palacios, M., Ewen, C., Pittman, E., Duggan, B., Carmine-Simmen, K., Fahlman, R., & Bleackley, R. (2014). Design and characterization of a novel human Granzyme B inhibitor. Protein Engineering Design and Selection, 9-17.

Cottrell, J. (2014). Patent No. US 8652511 B2. US.

Funk, C., & Rainie, L. (2015, January 29). Public and Scientists’ Views on Science and Society. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/29/public-and-scientists-views-on-science-and-society/

Prausnitz, M. (2004). Microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 581-587.

Jin, P., Li, F., Ruan, R., Zhang, L., Man, N., Hu, Y., . . . Wen, L. (2014). Enhanced transdermal delivery of epidermal growth factor facilitated by dual peptide chaperone motifs. Protein & Peptide Letters, 21(6), 550-555.

Jain, S., Jain, P., Umamaheshwari, R., & Jain, N. (2003). Transfersomes--a novel vesicular carrier for enhanced transdermal delivery: Development, characterization, and performance evaluation. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 29(9), 1013-1026.

Segal, D., & Michelson, R. (2015, April 17). Phosphagenics Initiates Oxycodone Patch Dosing in. Retrieved from Phosphagenics: http://www.phosphagenics.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2015-April-17-Phosphagenics-Initiates-Oxycodone-Patch-Dosing-in-Phase-2-Clinical-Trial.pdf

Young, R. (1992). Bacteriophage lysis: mechanism and regulation.Microbiological Reviews, 56(3), 430–481.

Acord, J., & Masters, M. (2004). Expression from the Escherichia coli dapA promoter is regulated by intracellular levels of diaminopimelic acid. FEMS Microbiol Lett., 235(1), 131-7.