Difference between revisions of "Team:Exeter/Experiments"

| Line 295: | Line 295: | ||

In order to obtain these spectra, the chromoproteins were grown up and expressed by NEB 10b <em>E.coli</em> cells in liquid cultures over about 24 hours, after which a protein extraction (using BugBuster) was carried out to extract the chromoproteins in the soluble phase. The proteins were then loaded into a clear microplate in 50 μl amounts and read using the BMG FLUOstar Omega reader over a range of wavelengths (400 to 850 nm). The peak maximas were then determined and marked, and compared to those previously reported. | In order to obtain these spectra, the chromoproteins were grown up and expressed by NEB 10b <em>E.coli</em> cells in liquid cultures over about 24 hours, after which a protein extraction (using BugBuster) was carried out to extract the chromoproteins in the soluble phase. The proteins were then loaded into a clear microplate in 50 μl amounts and read using the BMG FLUOstar Omega reader over a range of wavelengths (400 to 850 nm). The peak maximas were then determined and marked, and compared to those previously reported. | ||

| − | < | + | <br><u>Protocols used:</u></br> |

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li><a target="_blank" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/c/c7/Exeter_protein_extraction_BB_SOP.pdf">BugBuster protein extraction.</a></li> | <li><a target="_blank" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/c/c7/Exeter_protein_extraction_BB_SOP.pdf">BugBuster protein extraction.</a></li> | ||

Revision as of 03:24, 19 September 2015

Experiments & Protocols

Toehold experiments

In order to show that toehold switches could be developed to be used in our diagnostic test, we first had to show that the toehold can be expressed cell-free, and that it responds to the correct trigger RNA. To do this we have tested two toehold designs; Green_FET1J, and our own toehold designed to target a M.bovis mRNA, code-named ZeusJ. Before testing these designs in the lab, which is expensive due to the high cost of commercial cell-free kits, we decided to test the toeholds in silico using the online software package NUPACK.The use of the control toehold, Green_FET1, which has previously been reported to work as expected experimentally, allows for comparison of in silico between our toehold (Zeus), and the data of a function toehold. This can then be used to allow for an informed decision as to whether the toehold will work practically.

In silico testing:

The use of in silico testing in synthetic biology, and indeed science as a whole, is something which is not to be overlooked. While practical experimentation is still required and an important aspect of any project, the correct use of this kind of testing and modelling can allow for better informed experiments and more efficient testing, which can be extremely important when testing may take long time, or, as in this project's case, become expensive if many experiments are run. As our diagnostic test would be carried out in the field, where the temperature can not be easily controlled, it was important to determine the integrity of the toehold structures at different temperatures. In order to do this the analysis function of NUPACK was used to perform a melt between 0C and 70C on both toeholds. Briefly, the Green_FET1 toehold structure was shown to be correct from 25C, and the Zeus toehold was shown to be correct from 15C. A full discussion of the results from the NUPACK melt can be found on the results page. As well as being able to analyse the toehold's structures at different temperatures, the formation of toehold-trigger complex formations can be determined using free energies. As can be seen, as temperature increases, the ΔG of complex formation becomes less negative, meaning that toehold-trigger binding becomes less. Again, full discussion of this can be found on the results page. The main aim of this testing was to determine the most suitable toehold design to test in the lab, which therefore decreases resources and time spent testing toeholds which would not have been/had very little function. As well as using purely NUPACK to advise practical experimentation, two main models of the toehold/diagnostic system was created using MatLab. These are a simulation of the system, and a numerical model which could be used to determine optimal conditions for the test. Further explanation and discussion of these models can be found here.

Toehold ordering and construction:

Once our toehold (Zeus) had been designed and passed in silico testing, it and the control toehold (Green_FET1) needed to be ordered. In the paper where Green_FET1 had been experimentally validated, the transcription of it was under the control of a T7 promoter, however we wished to express our toehold under the control of a constitutive promoter, namely J23100. As we wished to use Green_FET1 not only as a control, but also as a comparison in functionality to Zeus, we decided to order Green_FET1 under the control of both a T7 and J23100 promoter. The toeholds were constructed as gBlocks containing overhangs for the standard pSB1C3 plasmid so as to allow construction of the toehold into the plasmid. The gBlocks were ordered from IDT (Integrated DNA Technology), and constructed using HiFi assembly from NEB (New England Biolabs). The constructs were then transformed, grown in liquid cultures, minipreped, and sent for sequencing. The DNA concentration was also determined by Qubit for use in later toehold testing.

Protocols used:Experimental validation of GreenFET1J (BBa_K1586000):

Once the toeholds had been constructed, it was time to begin characterisation. Firstly, initial testing of the toehold's response to various amounts (including no trigger) of the correct trigger (TrigGreen; GGGACUGACUAUUCUGUGCAAUAGUCAGUAAAGCAGGGAUAAACGAGAUAGAUAAGAUAAGAUAG) was carried out. The point of this experiment was to show that GreenFET1J works as expected, i.e. as more of the correct trigger is added, GFP production increases. To carry out this experiment, six S30 cell free reactions were set up following the S30 cell free SOP. In these reactions, 0.5 pmols of GreenFET1J (BBa_K1586000) as plasmid DNA was added to five of the reactions, and 0.5 pmols of BBa_R0040 (negative GFP control) was added to another. To the reactions containing GreenFET1J plasmid, the following amounts of TrigGreen were added; 0ng, 0.21ng, 52.31ng, 1046.09ng, and 2615.225ng. All reactions were then made up to a total volume of 50μl with nuclease-free water and incubated at 37C for three hours, after which fluorescence was read by the FLUOstar Omega reader (BMG). Repeats of this data were limited by the cost of the cell-free kits that we were using and time. For a discussion of the full results collected, visit the results page.

Protocols used:Adaptability towards different triggers:

An important aspect of the concept for our diagnostic test is that the focus of the test can be easily changed from one organism to another. The way in which this can be done is by changing the switch region of the toehold to bind a different trigger RNA from the organism being detected. Again, the utilities tool on NUPACK can be used to determine whether changing the switch region of the toehold would negatively affect the overall toehold structure. Once the new switch (and corresponding linker sequences) have been determined, these changes can be implemented into the current toehold structure using Q5 mutagenesis. Primers have been designed using NEB's base-changer tool (figure 1) which would allow the site-directed mutagenesis of the switch and corresponding linker region of the Zeus toehold into a switch region which could detect the same trigger RNA as Green_FET1, however due to time constraints this could not be validated experimentally in the lab. Although the changing of Zeus's target could not be shown, Q5 site-directed mutagenesis was successfully carried out in order to remove an illegal stop codon from the linker-end region of Zeus, and to remove an illegal PstI site from the GFP protein coding region of Green_FET1.

Protocols used:Further characterisation:

As has been stated previously, we wish our diagnostic test to be carried out in the field with little technical equipment/training, therefore the visualisation of the result must be simple. In order to do this, we decided that a colour change would be best, and that the expression of chromoproteins on activation of the toehold would be a good way to achieve this. In order to better inform ourselves and the model, and also to generate data which would be useful for testing toeholds with chromoproteins as the protein coding regions, we decided to further characterise some of the chromoproteins in the iGEM registry; amajLime, aeBlue, and eforRed.

Absorbance spectra:

To begin, absorbance spectra for the chromoproteins stated above were generated so as to find their maximum peaks, and therefore the wavelength at which that chromoprotein should be measured in further tests. For aeBlue and eforRed absorbance spectra have already been recorded, meaning that generating these spectra was for verification of data already submitted. For amajLime, an absorbance spectra has not previously been submitted to the registry, making this measurement an important part of further characterising this part for future teams and researchers to use. The absorbance spectra for amajLime is shown in figure 2. For all of the spectra measured, please see our results page, or the registry page for the chromoprotein of interest (links given above).

In order to obtain these spectra, the chromoproteins were grown up and expressed by NEB 10b E.coli cells in liquid cultures over about 24 hours, after which a protein extraction (using BugBuster) was carried out to extract the chromoproteins in the soluble phase. The proteins were then loaded into a clear microplate in 50 μl amounts and read using the BMG FLUOstar Omega reader over a range of wavelengths (400 to 850 nm). The peak maximas were then determined and marked, and compared to those previously reported.

Protocols used:

Standard curve - concentration vs. OD:

In order to allow for easy quantification of chromoprotein expression, we decided to construct standard curves of [chromoprotein] vs. OD at peak maxima for all three parts (amajLime, aeBlue, and eforRed), which is new information submitted to the registry. This would allow absorbance readings to give an estimate of the concentration of chromoproteins being produced in a system, for example with our project the amount of chromoprotein expressed in the cell free system, without needing to complete a lengthy protein extraction and run an SDS-PAGE gel, which is what we had to do in order to first quantify the amount of chromoprotein in our samples being used to construct the standard curve.

Visual limit of chromoproteins:

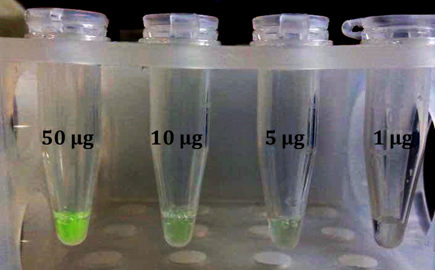

Something which would be very useful for testing toeholds that have chromoproteins as their indicators, and also something which we anticipate would be useful to other projects, is knowing at what amount a chromoprotein becomes easily visible. We therefore decided to determine visual limits for the three chromoproteins we have been characterising. To do this, we took samples of chromoproteins of known concentrations and diluted them so that they were all at the same concentration (1 μgμl-1) before carrying out further dilutions. Firstly, 1 μg of each protein was taken and made up to 50 μl (volume of our cell-free reactions) using de-ionised water and observed. This was then repeated for 5 μg and 10 μg. Shown in figure 9 is a picture of the visual limit for amajLime. For full results and discussion, see the results page.

Protocols:

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Use the arrow keys or mouse wheel to scroll through our SOPs. Click on an image to bring up the corresponding protocol.

Below is a list of all protocols, along with a downloadable ZIP folder containing PDFs of the protocols.

- E.coli transformation.

- gBlock Prep. and HiFi assembly.

- Competent cells preparation.

- Protein extraction (BugBuster).

- LB agar broth recipe.

- Agarose gel recipe.

- Running gel electrophoresis.

- Using the autoclave.

- DNA restriction digest.

- Thermo scientific FastDigest.

- DNA gel extraction.

- Cell glycerol stocks.

- Promega DNA ligation.

- Qiagen DNA miniprep.

- Liquid cell cultures.

- MgCl2 and CaCl2 recipes.

- Sterile 40% glycerol recipe.

- Qubit for DNA concentration.

- Dried DNA rehydration.

- Promega S30 cell free kit.

- Solid agar recipe for agar plates.