Riboswitches

Riboswitches are essentially mRNA molecules which have a regulatory section which controls whether or not the protein coding section is read or not. There are quite a few different types of riboswitches, each with different mechanisms. In general, the presence/absence of a ligand/trigger (from small metal ions, to amino acids, to proteins, to other RNA molecules), or changes in conditions such as temperature/pH, causes a change in conformation of the riboswitch which then either allows or stops the protein coding region from being read by a ribosome and the protein produced. Broadly, riboswitches can be put into two groups; those which act at the transcriptional level, and those at the translational level. This section will describe the general mechanisms of each type.

Transcriptional Control:

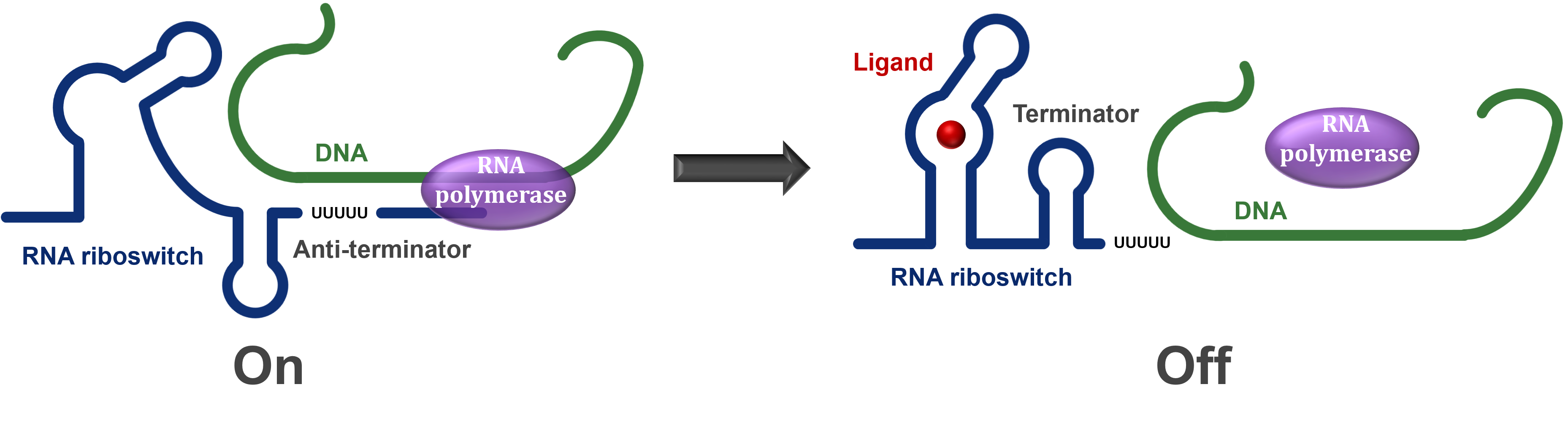

One of the main types of riboswitches controls the production of its own mRNA. During transcription, the riboswitch section of the mRNA is produced first while the rest of the coding section is being synthesised. This regulatory section is able to take on one of two structures depending on the presence/absence of a ligand/change in conditions.

If the riboswitch is turned off by the conditions/ligand presence, then it will cause a terminator to form in the mRNA and hence the RNA polymerase will stop transcription before the entire mRNA is produced, resulting in an essentially useless mRNA molecule. However, if the riboswitch is turned on, then an antiterminator is formed instead and the RNA polymerase is able to read through the entire mRNA and allow the protein to be expressed (Figure 1).

Translational control:

Riboswitches which act at the translational level usually work by sequestering the RBS (ribosome binding site) away from the ribosome, and hence stop translation of the mRNA and protein production. There are different mechanisms of sequestering and revealing the RBS. One of these ways is through cleavage of the riboswitch. In the absence/presence of a certain ligand/condition, the riboswitch can take on a conformation in which a cleavage site is revealed. If the riboswitch becomes cleaved, then the RBS can be released and accessed by a ribosome, which can then read the protein coding region of the mRNA. The cleavage of this riboswitch can be carried out by a protein/ribozyme, or in some cases by the riboswitch itself.

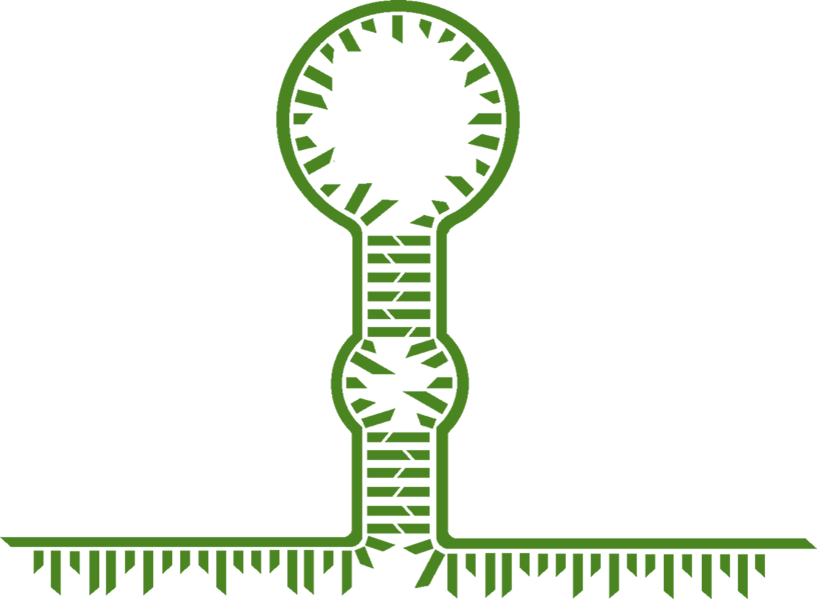

Another way in which an RBS can be sequestered is by being placed within a loop structure. When in a loop structure, the ribosome is unable to bind to the RBS sequence, and hence the protein can't be produced. If a ligand/condition changes the conformation of the riboswitch causing the loop structure to be removed, then the ribosome becomes able to bind to the RBS and read the rest of the mRNA (Figure 2).

Other types of riboswitches:

There are many types of riboswitches which are found in nature, each with a different type of mechanism. Our project is based around a specific riboswitch called a toehold switch. In the next section, the use of riboswitches in synthetic biology will be discussed in addition to a description of the structure and mechanism of a toehold switch.

Natural and Synthetic Toehold Switches

As has been discussed in the previous sections, RNA is an important molecule which is involved in many functions, including cellular regulation. Discussed in some detail in the previous section were riboswitches and the different types and mechanisms of action. For our project we have designed and improved upon a specific type of riboswitch; a toehold switch.

Toehold switches are riboswitches which regulate at the transcriptional level via RBS sequestration, and they are so named for the toehold structure which is an integral part of the riboswitch (figure 1). The basic mechanism of action is that an RNA molecule with a complementary sequence to that of the switch region of the toehold switch binds to the switch and causes the structure to open up, removing the toehold structure and revealing the RBS to allow the ribosome to bind. This mechanism is discussed in further detail below.

Green et al. 2014:

Riboswitches are found in abundance naturally in bacteria and work well as regulators, however synthetic biology is in the business of taking things found in nature and adapting them to our own needs. This is exactly what a research group led by Alexander Green (

Green et al. 2014) has done.

Riboswitches have the potential to be amazingly useful tools in a range of areas (discussed in more detail on the

'Future' page), however natural riboswitches have a few issues which means that they are not as easy to use as tools as they might be. One of the limitations of these riboswitches is that they tend to have a low dynamic range. The dynamic range can be thought of as the ratio between the high and low levels of a signal - in the case of riboswitches this would be the ratio between the levels of protein controlled by the riboswitch when switch is on vs. off. Typically, natural riboswitches have dynamic ranges of about 55 fold for riboswitches which enhance protein production, and about 10 fold for those which repress production. Another limitation is that natural riboswitches tend to have significant cross-talk (i.e. their activity is able to be altered by more than one input), which can make their specificity relatively low.

Synthetic biology is based on being able to easily engineer biological 'tools' to our own needs, however the structure of some natural riboswitches can make this difficult. Figure 2 shows a generic structure of many natural RNA-binding riboswitches. The region labelled as the 'switch region' is where the trigger RNA binds to activate the riboswitch. As can be seen, there are two regions which give constraints to the switch region sequence. The first of these are that a section near the middle of the switch region must show complementation to the RBS, the second is that the end of the region must follow the YUNR motif. The YUNR motif is a pattern of nucleotides which allows the binding of trigger RNA as either a loop-linear interaction, or a loop-loop interaction. These constraints increase the difficulty of engineering these riboswitches as trigger RNAs have the same constraints as the switch region. This can cause cross-talk between riboswitches within the same system as the triggers will have regions which show homology (the same/very similar) due to the same constraints being imposed upon them. If this issue could be worked around, then not only would it make riboswitches easier to engineer, but also reduce the issue of cross talk. In fact, this is exactly what Green

et al. did.

The research group led by Alexander Green designed a toehold switch of the general structure shown in figure 3. As can be seen, the constraints placed upon the switch region in natural riboswitches are no longer present.

Toehold switch mechanism:

The toehold switch mechanism is similar to any other RNA-binding riboswitch which regulates at the translational level. The trigger RNA binds to the switch region of the toehold in a linear-linear way, causing the toehold structure to open up. This then releases the RBS from the loop, allowing a ribosome to bind it in a linear-linear way. The ribosome can then read along the coding region of the toehold switch, hence giving off a signal. The Green

et al. 2014 paper shows that toehold switches of this design are able to have dynamic ranges of over 400 (comparable to below 60 for natural riboswitches), and a crosstalk level of below 12%. These changes mean that toehold switches are more suitable for use in synthetic systems.

Our Development:

These toehold switches show amazing potential in many areas, but we think that the area of diagnostics could greatly benefit from the development of toehold switches. This is why we decided to develop further the toehold switches made by Green

et al.. We plan to develop a standard toehold switch which can be changed in a relatively simple way in order to detect any given RNA, and hence diagnose many different diseases. We also wish to make a set of toehold switches with different indicators, mainly fluorescence, colour change, and luminescence. Another of our goals is to characterise toehold switches in a cell free system, and use the data from this to inform a model, which could then predict how other toeholds may act under the same conditions without carrying out many different experiments.