Difference between revisions of "Team:Cambridge-JIC/Practices"

Maoenglish (Talk | contribs) |

Maoenglish (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 416: | Line 416: | ||

<div style="width:160px;float:right;margin:10px"><center><p>For more information on TAPR, see <a href="#TAPR" class="blue">here</a>.</p><img src="//2015.igem.org/wiki/images/3/30/CamJIC-Practices-TAPROHL.png" style="width:150px"></center><br><center><p>For more information on CERN OHL, see <a href="#CERN" class="blue">here</a>.</p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/e/e1/CamJIC-Practices-CERNOHL.png" style="width:150px"></center></div> | <div style="width:160px;float:right;margin:10px"><center><p>For more information on TAPR, see <a href="#TAPR" class="blue">here</a>.</p><img src="//2015.igem.org/wiki/images/3/30/CamJIC-Practices-TAPROHL.png" style="width:150px"></center><br><center><p>For more information on CERN OHL, see <a href="#CERN" class="blue">here</a>.</p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2015/e/e1/CamJIC-Practices-CERNOHL.png" style="width:150px"></center></div> | ||

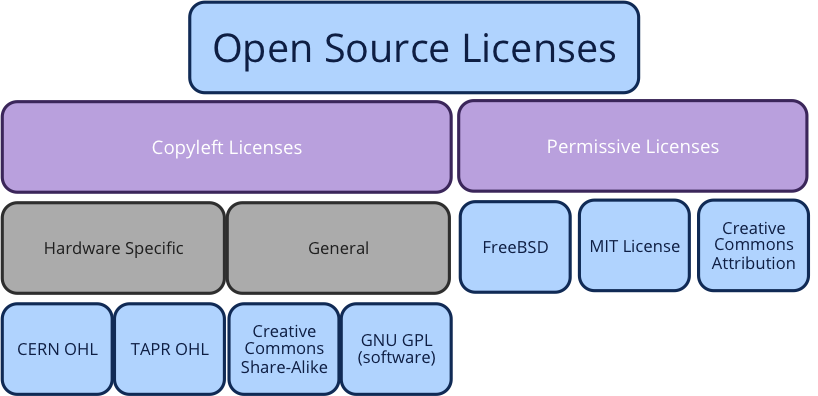

<p>Overall, the Copyleft requirements ensure that nobody is denied the rights to access the product and its documentation, including all downstream versions. In this sense the two hardware licenses (CERN and TAPR) are similar. The most significant difference between the TAPR OHL and the CERN OHL is that the TAPR OHL attempts to deal directly with the patent aspect of hardware licensing, and currently is the only license to do so [1]. As mentioned previously, the aspects of hardware such as manufacture and use mean that it is not covered by copyright, and instead must be regulated under patent law*.</p> | <p>Overall, the Copyleft requirements ensure that nobody is denied the rights to access the product and its documentation, including all downstream versions. In this sense the two hardware licenses (CERN and TAPR) are similar. The most significant difference between the TAPR OHL and the CERN OHL is that the TAPR OHL attempts to deal directly with the patent aspect of hardware licensing, and currently is the only license to do so [1]. As mentioned previously, the aspects of hardware such as manufacture and use mean that it is not covered by copyright, and instead must be regulated under patent law*.</p> | ||

| − | <p>This makes the license extremely powerful if the original creator of the hardware patented their creation: they can waive their | + | <p>This makes the license extremely powerful if the original creator of the hardware patented their creation: they can waive their IP rights under the license and provide full access to products and derivatives. However, a problem arises when the Licensor does not have patent rights over the creation [1]. The cost and complexity of obtaining a patent is a significant obstacle that the creator must attempt to overcome if they want to patent their creation. If anyone else asserts IP rights over the creation under license, and is awarded a patent, then access to the creation is no longer universal under the TAPR OHL.</p> |

<p>Ultimately the choice is yours: the TAPR OHL is particularly effective if the patent rights for the original work belong to the licensor, but it also has its drawbacks. As a license TAPR is older, but the CERN OHL has the backing of a strong community of physicists and does not deal as directly with patent rights.</p> | <p>Ultimately the choice is yours: the TAPR OHL is particularly effective if the patent rights for the original work belong to the licensor, but it also has its drawbacks. As a license TAPR is older, but the CERN OHL has the backing of a strong community of physicists and does not deal as directly with patent rights.</p> | ||

<p style="font-size:80%">* A reminder: copyright covers creative works such as designs, diagrams, software and other documentation. Patents are applicable to inventions and useful works as physical entities (the finished product). <br>[1] Keimform.de, (2009). The Tricky Business of "Copylefting" Hardware. <a href="http://keimform.de/2009/the-tricky-business-of-copylefting-hardware/" class="blue">[online]</a> [Accessed 10 Sep. 2015]</p> | <p style="font-size:80%">* A reminder: copyright covers creative works such as designs, diagrams, software and other documentation. Patents are applicable to inventions and useful works as physical entities (the finished product). <br>[1] Keimform.de, (2009). The Tricky Business of "Copylefting" Hardware. <a href="http://keimform.de/2009/the-tricky-business-of-copylefting-hardware/" class="blue">[online]</a> [Accessed 10 Sep. 2015]</p> | ||

Revision as of 09:48, 14 September 2015