Difference between revisions of "Team:Cambridge-JIC/Stretch Goals"

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

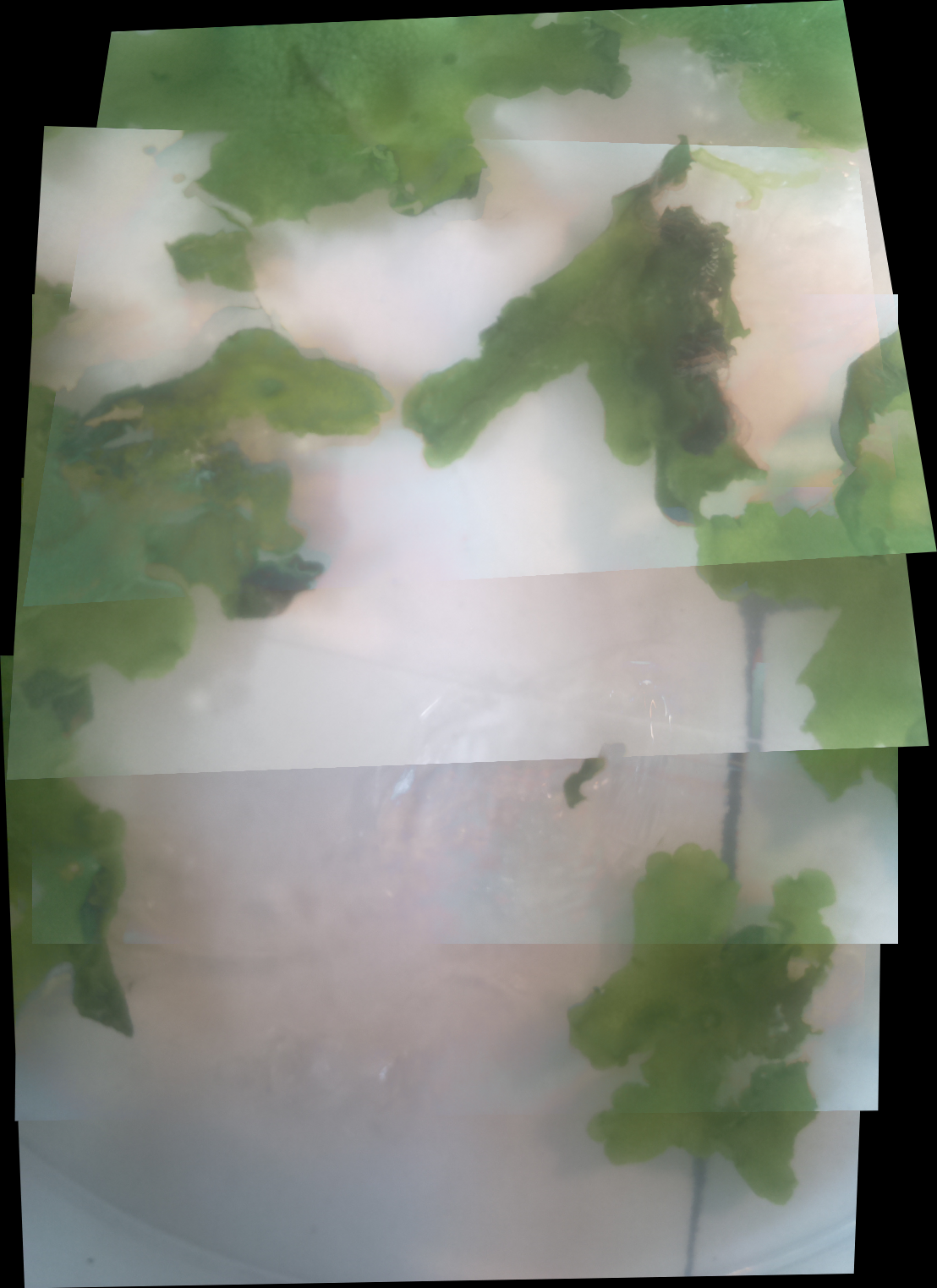

<p>We began to develop some python libraries to automatically manage this process, with an architecture as seen in the image to the right. The software in its current state is available within the 'lib' and 'hw' directories in our Github repository, which can be found on our <a href="//2015.igem.org/Team:Cambridge-JIC/Downloads">downloads page</a> (or go <a href="//github.com/sourtin/igem15-sw">here</a> to look for future revisions). It is based around a series of abstraction layers with the ultimate goal of hiding any underlying hardware and allowing easy automation of experiments. Our example use case focused on here is an automated screening system as described above whereby a macroscopic camera images a large sample set, software is then used to identify individual samples which are independently imaged by a microscopic camera, finally we screen these images using a range of image processing algorithms to identify different phenotypes. We can then select for these, e.g. by physically marking them, or even transferring them or destroying negative samples.</p> | <p>We began to develop some python libraries to automatically manage this process, with an architecture as seen in the image to the right. The software in its current state is available within the 'lib' and 'hw' directories in our Github repository, which can be found on our <a href="//2015.igem.org/Team:Cambridge-JIC/Downloads">downloads page</a> (or go <a href="//github.com/sourtin/igem15-sw">here</a> to look for future revisions). It is based around a series of abstraction layers with the ultimate goal of hiding any underlying hardware and allowing easy automation of experiments. Our example use case focused on here is an automated screening system as described above whereby a macroscopic camera images a large sample set, software is then used to identify individual samples which are independently imaged by a microscopic camera, finally we screen these images using a range of image processing algorithms to identify different phenotypes. We can then select for these, e.g. by physically marking them, or even transferring them or destroying negative samples.</p> | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

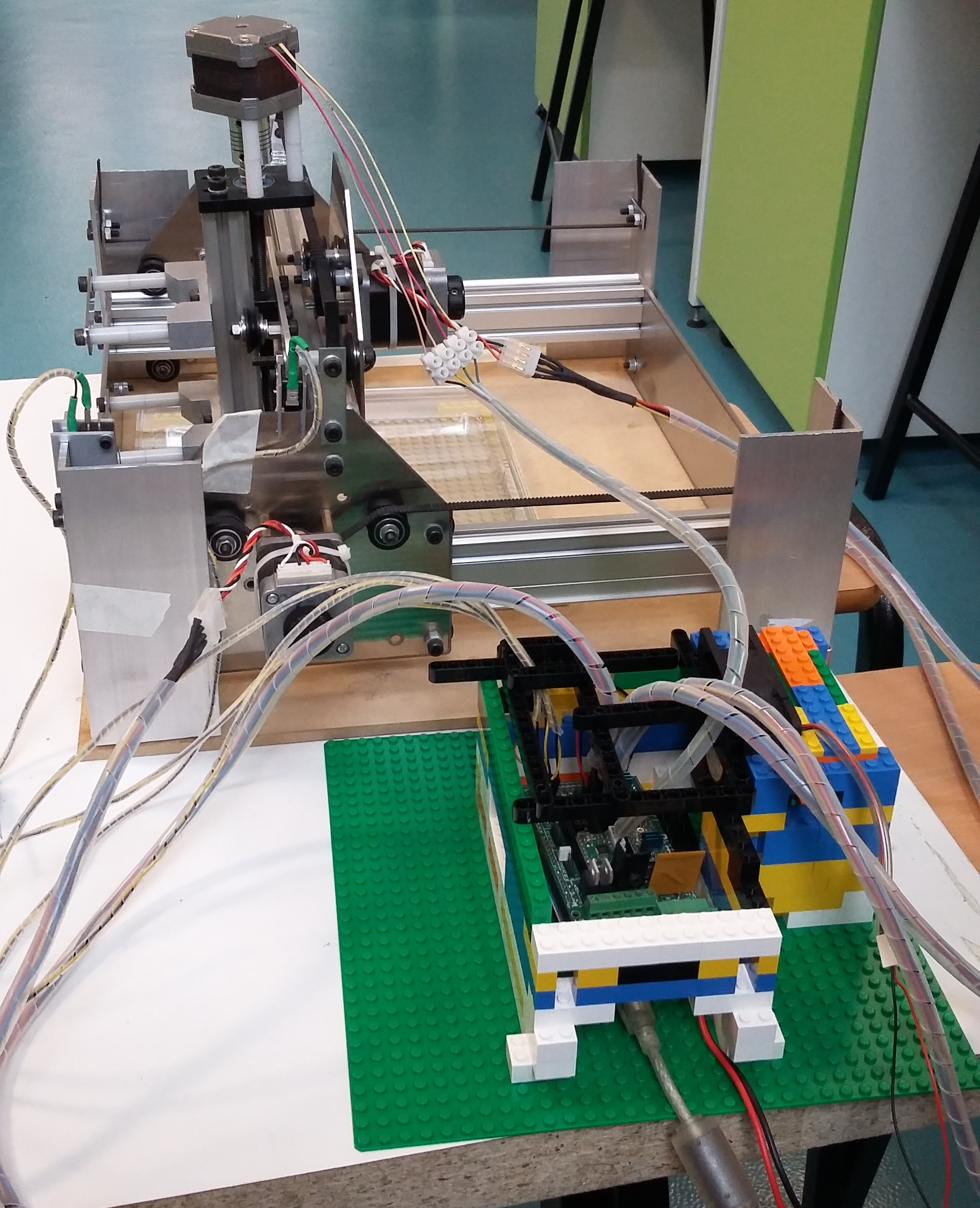

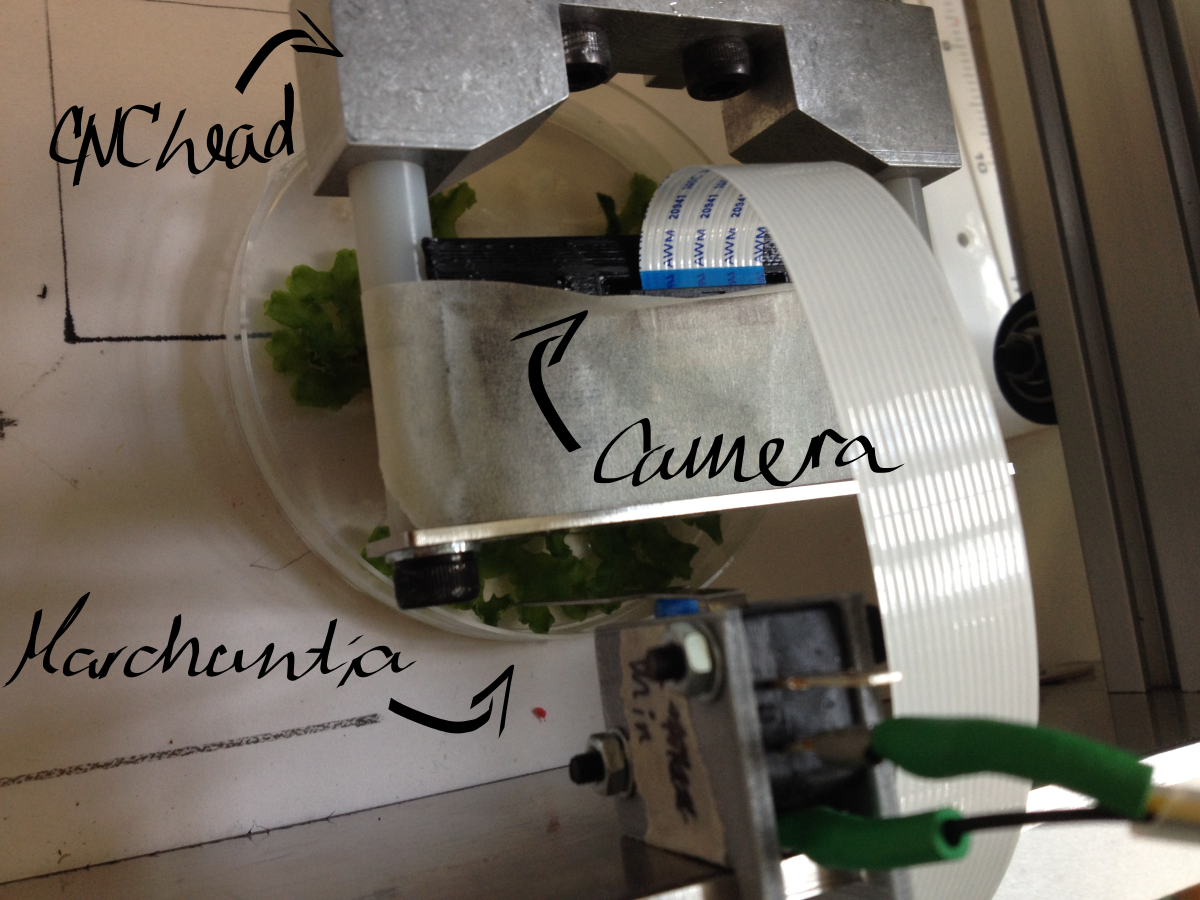

| − | <li>We start with the hardware itself. An xyz translation system, such as a Shapeoko or other CNC machine, is fitted with at least one 'head'. The most important head for our use is our OpenScope microscope. In our example we would also fit the Shapeoko with a macroscopic camera (or an overhead camera with a sufficiently large field of view). Further, we intend to have a marker. There are multiple ways to switch out heads; one simple way is a turret-like rotational mechanism, as used to switch out objectives in a desktop microscope. Another might be a magnetic mechanism to pick up and drop heads in a specially allocated bay within the xy stage. Our libraries are sufficiently general that hopefully we can automate even more complicated experiments, such as by adding in a Gilson pipette head.</li> | + | <li><p>We start with the hardware itself. An xyz translation system, such as a Shapeoko or other CNC machine, is fitted with at least one 'head'. The most important head for our use is our OpenScope microscope. In our example we would also fit the Shapeoko with a macroscopic camera (or an overhead camera with a sufficiently large field of view). Further, we intend to have a marker. There are multiple ways to switch out heads; one simple way is a turret-like rotational mechanism, as used to switch out objectives in a desktop microscope. Another might be a magnetic mechanism to pick up and drop heads in a specially allocated bay within the xy stage. Our libraries are sufficiently general that hopefully we can automate even more complicated experiments, such as by adding in a Gilson pipette head.</p></li> |

| − | <li>The next layer up is the driver software which interacts directly with this hardware. | + | <li><p>The next layer up is the driver software which interacts directly with this hardware.</p> |

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| − | <li>The Shapeoko itself is controlled by an Arduino Mega with a G-code interpreter installed which we can interface with to send complex movement commands (such as precision arcs) and to recalibrate at any time. Our driver can handle unexpected events such as cable disconnection with ease, recalibrating afterwards in case of unaccounted-for interruptions.</li> | + | <li><p>The Shapeoko itself is controlled by an Arduino Mega with a G-code interpreter installed which we can interface with to send complex movement commands (such as precision arcs) and to recalibrate at any time. Our driver can handle unexpected events such as cable disconnection with ease, recalibrating afterwards in case of unaccounted-for interruptions.</p></li> |

| − | <li>We anticipate that most other heads will be controlled by Arduinos (or a Raspberry Pi for the OpenScope camera, due to the high bandwidth requirements). The OpenScope software can be directly leveraged for the camera heads.</li> | + | <li><p>We anticipate that most other heads will be controlled by Arduinos (or a Raspberry Pi for the OpenScope camera, due to the high bandwidth requirements). The OpenScope software can be directly leveraged for the camera heads.</p></li> |

| − | <li>In our calibration tests we attached a pen to the Shapeoko head. This was much simpler as we could control the z axis to apply the pen at will, without any additional arduinos to interface with.</li> | + | <li><p>In our calibration tests we attached a pen to the Shapeoko head. This was much simpler as we could control the z axis to apply the pen at will, without any additional arduinos to interface with.</p></li> |

| − | <li>We also have some virtual hardware in our examples and tests to demonstrate the abilities of the software, such as a camera which can navigate a gigapixel image of the Andromeda galaxy</li> | + | <li><p>We also have some virtual hardware in our examples and tests to demonstrate the abilities of the software, such as a camera which can navigate a gigapixel image of the Andromeda galaxy</p></li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| − | These drivers use a common software class to unite their differences under a common language. In this way we can abstract away from all the intricacies of each hardware head and control the hardware with ease.</li> | + | <p>These drivers use a common software class to unite their differences under a common language. In this way we can abstract away from all the intricacies of each hardware head and control the hardware with ease.</p></li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

Revision as of 15:25, 18 September 2015

To integrate OpenScope onto a desktop translation system (CNC), such as the

To integrate OpenScope onto a desktop translation system (CNC), such as the