Difference between revisions of "Team:Cambridge-JIC/3D Printing"

Simonhkswan (Talk | contribs) |

KaterinaMN (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<style> | <style> | ||

h1.guide{ | h1.guide{ | ||

| − | font-family: 'Hiragino Sans GB', 'Open Sans'; text-align: center; font-size: 32px; padding-bottom: 5px; | + | font-family: 'Hiragino Sans GB', 'Open Sans', 'Sans Serif'; text-align: center; font-size: 32px; padding-bottom: 5px; |

} | } | ||

h2.guide{ | h2.guide{ | ||

| − | font-family: 'Hiragino Sans GB', 'Open Sans'; background-color: #ddd; margin-bottom: 6px; padding-bottom: 5px; | + | font-family: 'Hiragino Sans GB', 'Open Sans', 'Sans Serif'; background-color: #ddd; margin-bottom: 6px; padding-bottom: 5px; |

} | } | ||

h3.guide{ | h3.guide{ | ||

| − | font-family: 'Open Sans'; background-color: #eee; margin-bottom: 6px; padding: 5px; | + | font-family: 'Open Sans', 'Sans Serif'; background-color: #eee; margin-bottom: 6px; padding: 5px; |

} | } | ||

p.intro{ | p.intro{ | ||

| − | font-family: 'Open Sans'; | + | font-family: 'Open Sans', 'Sans Serif'; |

} | } | ||

p.guide{ | p.guide{ | ||

| − | font-family: 'Open Sans'; | + | font-family: 'Open Sans', 'Sans Serif'; |

} | } | ||

section.guide-section a:link, section.guide-section a:visited{ | section.guide-section a:link, section.guide-section a:visited{ | ||

Revision as of 11:21, 17 September 2015

So you think you can 3D print?

A short guide to 3D printing.

3D printing has been an essential tool in the development of the OpenScope. The ability to rapidly prototype, edit and create objects has allowed our team to design a microscope accessible to anyone and easy to modify to tailor to your own needs.

This short guide gives an overview of the things we have learned and had to consider over the past 3 months of printing and should at least get you started in the art of 3D printing.

Getting Started

You will need a 3D printer, filament, and 3D CAD software before you get started on the road to producing your own 3D gems.

Types of printers

There are many 3D printers available on the market that come within a wide range of costs with different pros and cons. Before purchasing a printer, consider what you are willing to create and check out a guide such as “Which 3D Printer Should I Buy?”

Things to consider are: build plate size (eg. the old printer in our lab was too small to print our microscope in full size), z-axis resolution, features such as bed heating (see Sticking to Base and Warping), and a dual extruder (See Filament).

Our team upgraded to an Ultimaker 2 and after some configuring, found that it perfectly suited our needs.

Filament

The two main types of filament used are ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) and PLA (Polylactic Acid). Other filaments also exist (some are even conductive) but these two are the standard.

ABS has a glass transition temperature around 105°C. As it can withstand higher temperatures than PLA (65°C) it is often used in industry.

At high enough temperatures ABS breaks down into its constituent chemicals, one being butadiene which is carcinogenic to humans. (Note: The breakdown temperature is above 400°C, which is much higher than the operating temperature for 3D printing. Therefore, normally the use of ABS does not impose a safety hazard.)

PLA is a biodegradable plastic, derived from plants as opposed to petroleum and natural gas, which makes it a green alternative to ABS. The chassis of the OpenScope is made of PLA, it is biodegradable and recyclable.

We found that PLA was able to handle bridging much more reliably than ABS. It is also less brittle than ABS, which our microscope takes advantage of in its flexure mechanism. PLA also sticks to the base of the 3D printer more easily and warps less than ABS. Therefore, we recommend avoiding the hassle and sticking with PLA as your choice of filament – it also comes in a huge variety of colours! Bear in mind that different colours imply slightly different chemical constitution of the filament and so print quality may vary between colours.

Software

To make the design of OpenScope easily modifiable to others, we used the program OpenSCAD, a free multiplatform CAD (computer aided design) program that is easy to learn. An hour of experimenting is all you need to start creating and there is a massive community based around OpenSCAD to inspire your own designs. We have made an effort to make the design of our creation as simple and modular as possible whilst still being functional as a microscope.

OpenSCAD is not an interactive modeller, but rather a 3D-compiler which reads a script file that describes the object you wish to render in 3D. Each object is defined geometrically, with its characteristic sizes, and positioned in an [xyz] coordinate system. This different approach to CAD modelling makes it great for creating advanced 3D printing files (.stl). With a little bit of algebra, our script files describing each component on our website have been parametrically defined, so if you need a microscope that is slightly bigger, taller, or shorter, you can simply change a few numbers at the start of the file! We encourage anyone to edit the details of the code too, though, make sure you structure the code so that it is easy for other (and yourself!) to reedit it later.

Design Process

It is important to note that the object your design in your 3D CAD software and the object the 3D printer creates are two different things. 3D printers still have their limitations. Once you get designing, here are a few things to be aware of, they are common issues that people run into.

Bridges & Overhangs

3D printers that use a thermoplastic filament work by printing layer upon layer. Therefore, a problem arises when the printer tries to print a layer over nothing. If your design has some sort of overhang one option is to print supports, the issue with this is cleanly removing the supports from the final print - it be hard or sometimes impossible to do. Most printers can cope well with overhangs that have an incline greater than 45 degrees as the plastic layer underneath is able to support the protruding plastic above. The alternative is to print a bridge. This is simply a flat overhang that is supported at both ends.

When printing bridges and overhangs, such as the ones in OpenScope, the cooling fans need to be on so that the plastic cools as it leaves the extruder (this can be at a compromise to prevent warping). Bridges are printed best when they simply go from one support to another with no holes or features in the way. We had to deal with problematic bridges when printing the CCD cube and the stage of our microscope. Particular shapes can always be made by stacking bridge upon bridge.

Sticking to Base

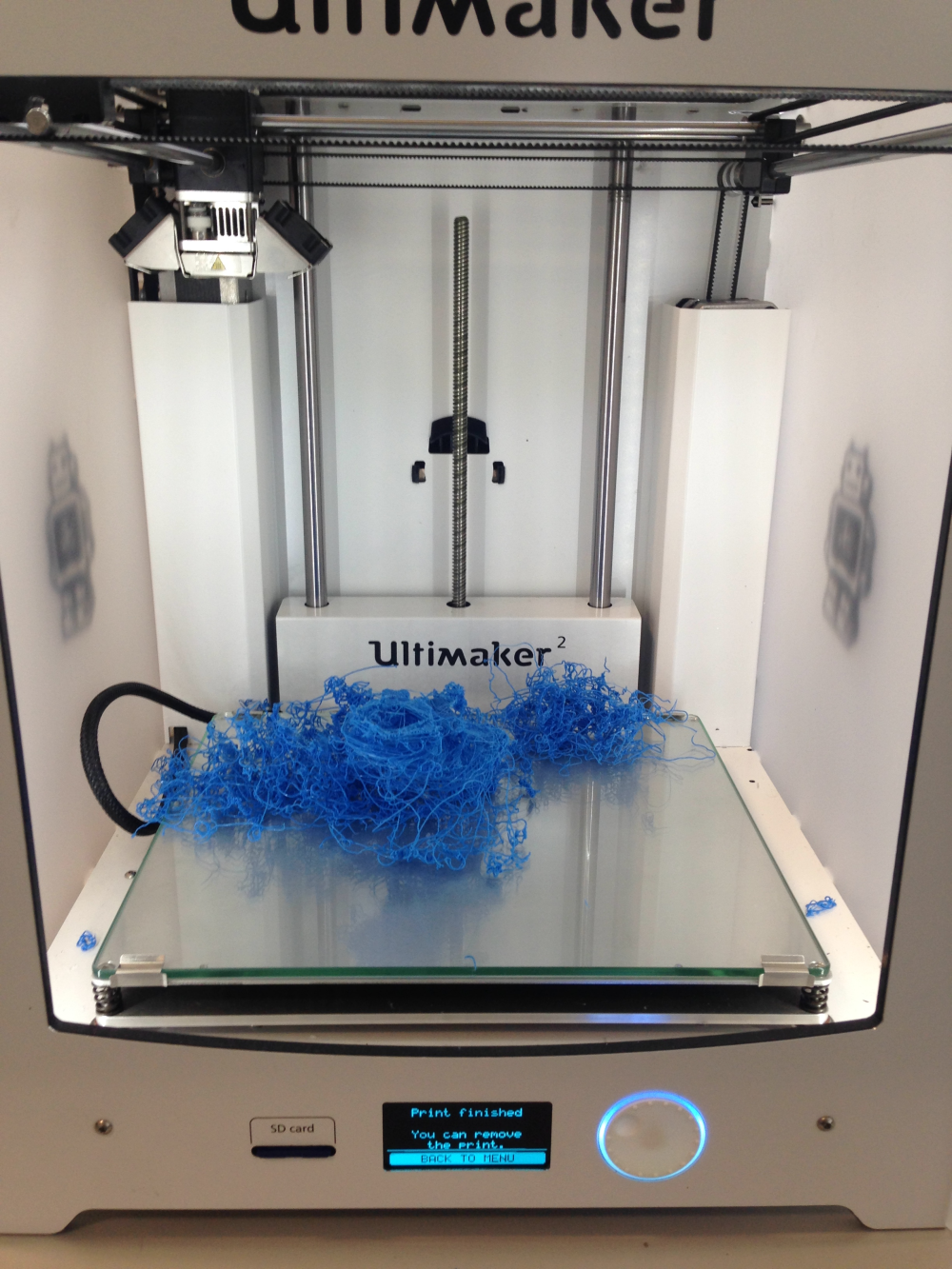

The first issue we experienced when 3D printing was keeping our objects stuck to the bed of the printer. If the object slips mid-print it can often be dragged around resulting in a tangled mess of plastic. Those who choose PLA will have less problems with slipping than those using ABS.

The first issue we experienced when 3D printing was keeping our objects stuck to the bed of the printer. If the object slips mid-print it can often be dragged around resulting in a tangled mess of plastic. Those who choose PLA will have less problems with slipping than those using ABS.

An unlevelled printer bed can be a common reason for misprints: when the print bed is too low, the thermoplastic is not pushed down enough and cannot stick; when it is too high, there is no room for filament to extrude, so the nozzle gets clogged and the feeding gear begins to grind into the plastic. If this happens, take the filament out and remove the worn out piece.

The Ultimaker 2 printing bed has 3 screws which are to be calibrated and the included manual suggests using paper. We have found that it is preferable to position the bed slightly lower than the manual advises though. Another useful feature of the Ultimaker 2 is the heated print bed (almost essential for ABS) to keep the base near its glass transition temperature, reducing the chance of warping and unsticking.

We found that an easier method of calibrating the bed was to print a large square (one layer high) and observe the filament on the bed. It is much easier to then fine tune the screws so that the filament is pressed onto the bed enough to stick, but the bed isn’t too high so that no filament can be extruded.

Note that the higher the print bed is, the less likely the object will detach or warp, but the more likely that your print will develop elephant’s feet (see below).

Warping

Like most materials, PLA and ABS are subject to thermal expansion/contraction (ABS more so than PLA). As each layer of plastic is layed down hot and cools down, the uppermost layer of your print is constantly contracting. This can cause objects to warp upwards around their edges and corners and is a major problem with large flat prints in particular. There are some clever tactics to prevent warping by modifying your .stl files before printing (see this video for an example), though, we have found that printing an object with a brim and keeping the print bed calibrated does the trick with PLA. A brim is simply a one layer outline that is printed around your object to keep it stuck down. Programs such as Cura (the official software for the Ultimaker) allow you to add this to your .stl files before they are to the printer.

Like most materials, PLA and ABS are subject to thermal expansion/contraction (ABS more so than PLA). As each layer of plastic is layed down hot and cools down, the uppermost layer of your print is constantly contracting. This can cause objects to warp upwards around their edges and corners and is a major problem with large flat prints in particular. There are some clever tactics to prevent warping by modifying your .stl files before printing (see this video for an example), though, we have found that printing an object with a brim and keeping the print bed calibrated does the trick with PLA. A brim is simply a one layer outline that is printed around your object to keep it stuck down. Programs such as Cura (the official software for the Ultimaker) allow you to add this to your .stl files before they are to the printer.

Another option to combat warping is to turn the cooling fans off and keep the whole object warm until it is complete, although the printer then loses its ability to print overhangs and bridges properly. When printing the OpenScope stage, we used a brim and with the fans on as normal. The brim is very easy to pull/cut off the 3D printed piece when it has cooled down.

Elephant’s Feet

'Elephant’s Feet' refers to the issue when base layers of 3D printed objects are wider than the layers above. This usually happens when the print bed is slightly too elevated, so the first layers are flatter and wider (by 0.2mm-0.8mm) than the layers above. Printing a cube usually demonstrates this problem. Most of our prints have this problem, but we did not aim to oppose it as we want to keep everything stuck to the print bed whilst printing. To fix the problem, you can edit your objects to have a chamfer around the base edges (a rough guide: at 45 degrees, 0.5mm and not curved). We have taken this into account for several parts. For objects that must slot into other parts, the holes are printed slightly larger than they should normally be – remember the values specified in your CAD model and the values printed are always slightly different. Generally, getting two 3D printed objects to fit together can be an iterative process.

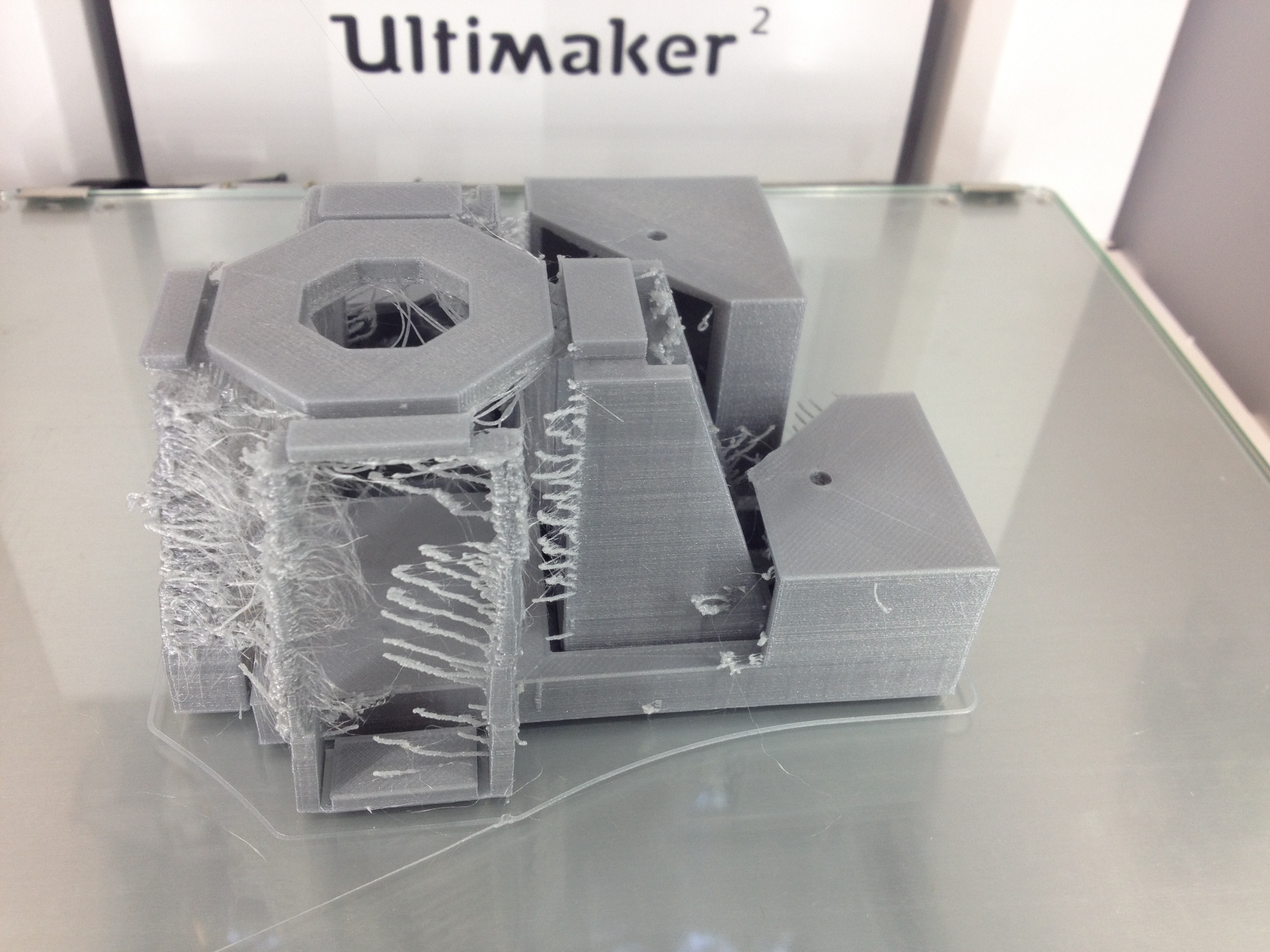

Stringing

Sometimes, prints can come out with little pieces of plastic ‘stringing’ off the object. Increasing the travel speed reduces the time for molten plastic to leave little strings of plastic behind. The print speed, however, does not affect stringing. As a general rule, slower print speeds result in higher quality prints. It is always a compromise for the print time.

Sometimes, prints can come out with little pieces of plastic ‘stringing’ off the object. Increasing the travel speed reduces the time for molten plastic to leave little strings of plastic behind. The print speed, however, does not affect stringing. As a general rule, slower print speeds result in higher quality prints. It is always a compromise for the print time.

The Message

Finding the right settings to print high quality prints is a continuous process; adjusting the settings of your printer and being aware of how certain issues are caused will enable you to quickly improve your creations.

Post processing

After printing, there are still many things that can be done, which can really transform the plastic. As the printing is done layer by layer, vertical faces are very often much rougher than the horizontal surfaces – take this into account when considering which side is your object base. All the surfaces can be smoothened with sand paper, though this can take quite a long time. One advantage of ABS is that spraying acetone onto it dissolves a very thin layer of the plastic and greatly smoothens your product. This is not as effective on PLA and can actually bleach the colour of the object.

Painting and using resin are two other methods of making artwork of your 3D prints. Apart from superglue, we chose not to have much post processing, in order to make the microscope simple to recreate. Of course, it is up to you how you want to decorate your own!

ABOUT US

We are a team of Cambridge undergraduates, competing in the Hardware track in iGEM 2015.

read moreLOCATION

Department of Plant Sciences,

University of Cambridge

Downing Street

CB2 3EA

CONTACT US

Email: igemcambridge2015@gmail.com

Tel: +447721944314