Team:TJU/Design

Design

Naturally, we can barely find microorganisms that live in isolated niches, instead, there are full of various material, energy and information communications. In our project, we have been aware that Shewanella can efficiently use lactate as carbon substrate for power production. Therefore, high-yield of lactate seems critical for current generation and also for a reliable interaction between different species. Moreover, flavins mediated EET pathway is able to directly affect the electrons transfer and output, which inspired us to adopt flavins as a factor to achieve information interaction. Based on the research above, we further developed and optimized a co-culture system with three strains of bacterium in the MFC to achieve a more robust and efficient system. Apart from that, we designed a pH sensing and proteolysis system as a practical tool for troubleshooting and an attempt to benefit the future researchers.

1 Lactate producing system

Generally material flow, information flow, together with energy flow are key factors to regulate relations among bacterial consortium. Material flow, in particular, known as the most reliable and convenient method, is adopted in our construction. Typically the substances of the flow are often necessary nutrition for bacterial survival such as essential amino acid and carbon sources.

Shewanella oneidensis can generate electricity with a relatively narrow range of carbon substrates, including lactate, acetate, formate, pyruvate and some amino acid.[1] It has been shown that Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 prefers the utilization of lactate as an energy-favorable carbon substrate as lactate-based biomass yield was higher than that for either acetate or pyruvate. Similarly, the lactate-based growth rate was much higher as well.[2] Thus, lactate is the most suitable carbon source and also the key mediator for the material flow in our system.

In order to develop a proper mechanism for lactate supply, we use Escherichia coli, a well characterized bacterium, to produce lactate. Previously, researchers has developed a system that was able to produce 142.2 g/L of L-lactate with no more than 1.2 g/L of by-products accumulated by knocking out ldhA and lldD and inserting L-LDH.[3] Consequently, E.coli has many advantages as a host for production of lactic acid, including the ability to produce optically pure lactate, rapid growth under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, and its simple nutritional requirements.[4]

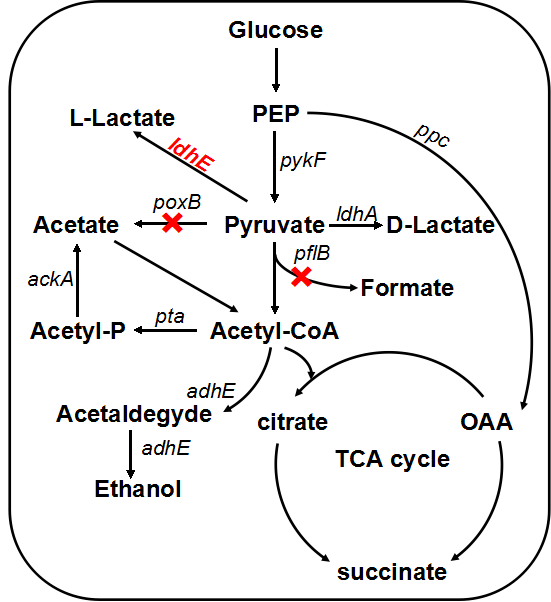

Escherichia coli grows fermentatively in glucose-containing medium under anaerobic condition with formation of a mixture of organic acids (lactate, acetate, formate and succinate) and ethanol, and lactate only takes no more than 50% of the total metabolites.[4] Since we need to provide enough material support for the growth and metabolism of Shewanella under anaerobic condition, we decided to enhance the yield of lactate by genetic engineering through two strategies:

1.1 ldh- Lactate dehydrogenase(LDHE)

LDH is an enzyme found in nearly all living cells (animals, plants, and prokaryotes), which catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate with NADH serving as the coenzyme. Naturally, E.coli can produce D-lactate by itself but the amount and the activity of lactate dehydrogenase becomes the bottleneck. We found that those two factors of enzyme are hard to change dramatically in vivo. So in our project, we intend to introduce high-yield exogenous L-(+)-lactate dehydrogenase gene (ldhA) from Lactobacillus, which can convert the redundant pyruvate and subsequently provide even more sustenance for Shewanella. Similar metabolic pathway has been found in a variety of organisms, to distinguish the differences, we renamed the heterogenous L-lactate dehydrogenase gene ldhE while homogenous one keeps original ldhA.

After we transferred our part into E.coli BL21, we found there was little difference between the experimental group and control group.

In order to enhance the transformation efficiency from glucose to lactate, as well as improve the characterization of our ldhE part, we decided to knockout the the pflB and poxB.

1.2 pflB knockout

PFL is a crucial enzyme in the glucose metabolism under anaerobic condition, which can catalyze one molecule of pyruvate to one molecule of formicate and one molecule of acetylcoenzyme A (AcCoA). According to metabolic pathway, pyruvate is consumed both in the PFL and LDH reactions. In the wild type E. coli, LDH reaction is not as competitive as the reaction through PFL, and therefore, knockout of the PFL related genes will contribute to redistribute the metabolic flux. When the PFL pathway is blocked, E. coli will conceivably alter the distribution of these products to overcome the imbalanced reducing equivalents caused by the pathway knockout. Therefore, knockout of pflB not only decreased the carbon flow to acetyl-CoA under anaerobic condition but also reduced the anaerobic consumption of NADH through reductive TCA. [5]

After the knockout of pflB, though the growth rate was slightly slowed down, the yield of lactate of engineered strain was improved greatly and showed a significant difference from the wild type MG1655. From the result, we can see our part functioned as expected.

1.3 Knockout strategy

For genes knockout, we adopted a effective, easy-to-use two-step system in which the cell is first transformed with a helper plasmid harboring genes encoding the λ-Red enzymes, I-SceI endonuclease, and RecA. λ-Red enzymes expressed from the helper plasmid are used to recombineer a small ‘landing pad’, a tetracycline resistance gene (tetA) flanked by I-SceI recognition sites and landing pad regions, into the desired location in the chromosome. After tetracycline selection for successful landing pad integrants, the cell is transformed with a donor plasmid carrying the desired insertion fragment; this fragment is excised by I-SceI and incorporated into the landing pad via recombination at the landing pad regions.[6]

First round of recombineering consists of three rounds of PCR for the construction of recombinant genome cassettes which subsequently positively selected by selection markers such as Tetr. In the second step, TetA marker was released by simultaneous induction of I-SceI and Red recombinase expression which serves as a negative selection.[7] (More details in Method.)

2 Flavins producing system

Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, a facultative anaerobe, has been widely used as a model anode biocatalyst in microbial fuel cells (MFCs) due to its easiness of cultivation, adaptability to aerobic and anaerobic environment and both respiratory and electron transfer versatility. [8]

Particularly, EET pathway can be subdivided into direct EET and mediated EET and the latter one limits the efficiency of electron transfer between bacteria and electrode due to the deficiency of electron mediator. To regulate relations of energy and information in the consortium, flavins hold the key to success.

It is widely accepted that interfacial EET is the rate-limiting step in the EET processes which can be relieved by some redox active molecules such as quinines and metal-centered porphyrin-ring derivatives. However, those redox active molecules are generally costly and toxic to anodic electricigens. Besides, Shewanella is capable of utilizing self-secreted flavins like riboflavin (RF) to accelerate EET, which is much more efficiently than other exogenous active molecules. More specifically, riboflavin (RF) and flavin mononucleotide (FMN) enhance EET more than five times, with much lower concentrations than those needed for anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) shuttling. So we choose flavins as one entry point to enhance the electricity output of MFCs. [9]

In EET model, outward current flows from interior of cells to outer membrane (OM) and extracellular anodes through a metal-reducing conduit (Mtr pathway), where electrons (from NADH, the intracellular electron carrier) flow through the menaquinol pool, CymA (inner membrane [IM] tetraheme c-type cytochromes [c-Cyts]), MtrA (periplasmic decaheme c-Cyts), MtrB (β-barrel trans-OM protein) and finally to MtrC and OmcA (two OM decaheme c-Cyts). However, the principle of how flavins function still remains controversial. [10]

Traditional model demonstrates that flavins carry the electrons from OM c-Cyts to electrode by diffusion, which has been in debate due to thermodynamic disproof. Recently, another interfacial EET model was proposed, where flavin may serve as a co-factor binding to OmcA or MtrC to dictate EET. Fully oxidized flavin (Ox) accepts one electron from reduced heme of OM c-Cyts, and binds to OM c-Cyts as a cofactor in the semiquinone (Sq) form with shifted potential. Ox/Sq redox cycling in OM c-Cyts donates electrons to electrodes in a one electron reaction mode via direct contact.[10]

Although Shewanella uses endogenous flavins to mediate electrons, the amount of its production is deficient and multi-tasks brought by self-engineering may also reduce the transfer efficiency. As a consequence, we had two strategies to construct the zymophyte and further improve the production. Firstly, we introduced flavin producing genes using the E.coli as chassis. Secondly, we get an engineered B.subtilis strain from the lab of Dr. Tao Chen [11](more detail in attribution)

Based on the EET pathway theory, we suggest that by maximizing the amount of flavins, we may significantly enhance the EET efficiency and achieve a relatively high power generation.

We found a part BBa_K1172303 in Part Registry constructed by 2013 Team Bielefeld-Germany which was also aimed at producing riboflavins. However, the gene cluster showed a maximum output of 6 mg/L even with a strong promoter, which was insufficient to maintain a high and constant efficiency of EET pathway in our co-culture system. So we decided to optimize the part BBa_K1172303 to enhance the production of riboflavins.

As we learn from metabolic flux (figure 2), it reveals the relevant pathways of riboflavin production and engineering strategies for riboflavin production. In their previous research(Tao, et al) [7] ,they construct a high-yield E.coli strain with a yield of 229.1 mg/L. Based on their study, we constructed a flavin producing part (ribABDEC cluster) named EC10.(as shown in figure 11a). The part(BBa_K1696011) we designed, compared with BBa_K117230, has been well optimized and the yield of that reached 17 mg/L.( as shown in figure 13). We can see from the results, the functionality of their parts has successfully improved.

In the meanwhile, based on co-factor model, EET pathway points out that FMN plays a critical role in electron transfer. Through the study by Dr. Tao Chen, they have weakened the RBS upstream of ribC to divert more of the material flux to RF production.[7] Based on their viewpoint, we got further to design a strong RBS sequence upstream of the ribC and we rename the new part as EC10*(BBa_K1696010). The yield of EC10* reached 90 mg/L(as shown in figure 11b). The strong RBS before ribC sequence can lead to the FMN accumulation while riboflavin consumes a bit, which may in turn, result in increasing both for riboflavin and FMN as a whole.

When we characterized our part, we were not able to detect the FMN for lacking proper equipments. However, we were surprised to find that the production of EC10* was even better with a larger output of riboflavins. For riboflavin measurements, culture samples were diluted with 0.05 M NaOH to the linear range of the spectrophotometer and the A444 was immediately measured, according to the Dr. Tao Chen’s method [7]. As for the reason of production improvement of RF, we speculate that the strengthening of ribC gene can improve both the RF and FMN yield through the flavin metabolic pathway.

3 Co-culture MFC -- Division Of Labor

Microorganisms rarely live in isolated niches. One reason is that the maintenance of viability of these microbes may need supplementary metabolites or other signaling chemicals provided by other microbes in the ecosystems and communities.[11] Conforming to the trend of revolution, we apply the bacterial consortium in our MFC for greater power generation and increased duration.

Apart from the universal trend of nature, the mixed culture shares some unique advantages particularly in our MFC. For example, Shewanella originally can merely use few simple carbon substrates like lactate, acetate, formate, pyruvate and some amino acid.[1] However, our consortium as a whole can expand the absorption range of carbon resources and develop a more complex diagram of carbon input for Shewanella. Also, our intention is able to achieve comprehensive functions through “Division Of Labor” that monoculture can hardly manage. For instance, if we use only Shewanella to supply electricity, the production of flavins as well as other related reaction will inhibit current creation. These are fundamental reasons that we adopt the “mix” strategy in our project.

3.1 First Trial

Our experiment started with monoculture of Shewanella, in which we have found several important conclusions that might be used in the later trials: (i) Shewanella alone cannot take good use of glucose as the mere carbon source to generate power. (ii) Voltage has been improved when we add flavins to the monoculture medium, which proved that flavins indeed would help the power enhance. (iii) As an attempt to choose a proper substance being used in the experiment, we put sodium lactate into service and found that Shewanella could achieve power output.

3.2 Second Trial:

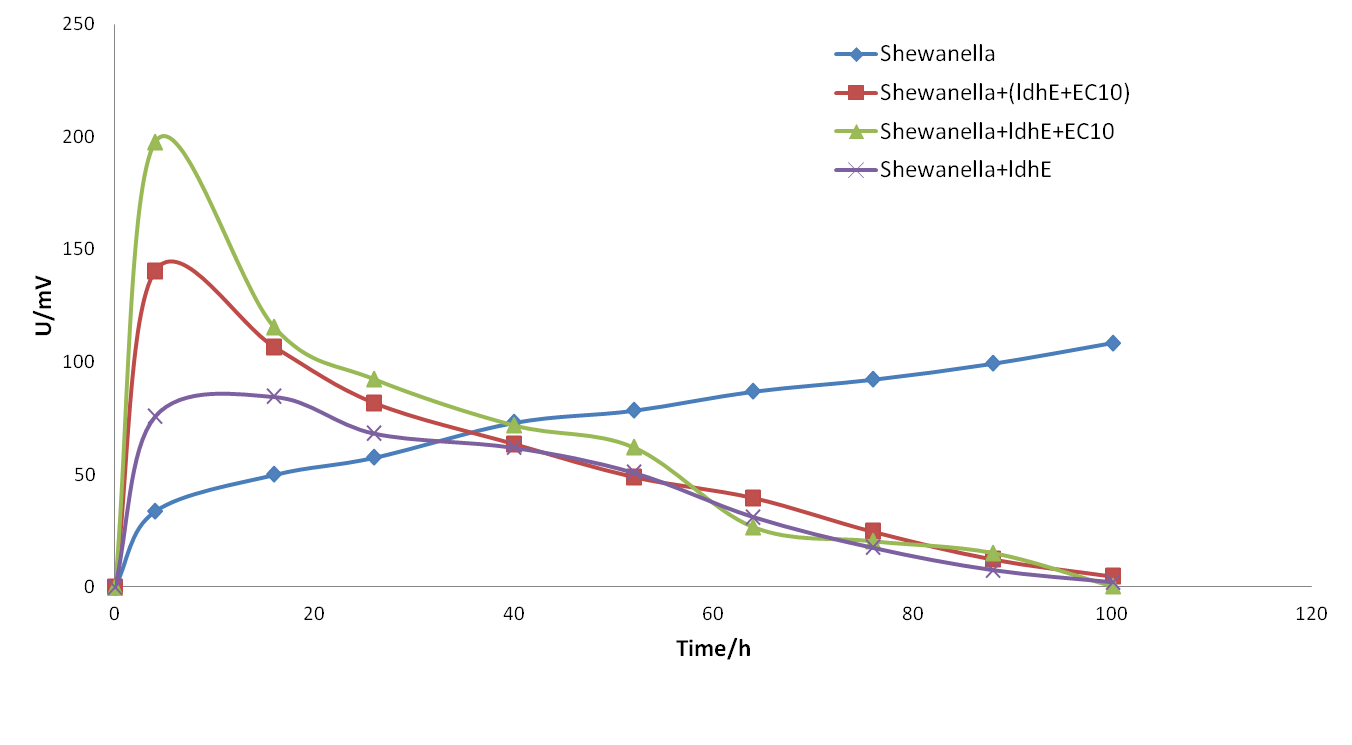

Since we’ve constructed the lactate producing strain (ldhE), the flavin producing strain (EC10) and an engineered strain bearing both ldhE and EC10, we initiated our co-culture experiment with different division of labor.

3.3 Third trial

When we have preliminarily optimized the bacterial proportion and medium compositions, we got a significant improvement of the electricity output in spite of the relatively short sustaining time.(shown as follows)

We also attempted to put the fermentation bacteria into the system some time after Shewanella. However, the later joining of fermentation bacteria will the stability of the system so that the output oscillated for a period of time. We can see from the figure 18, even though the lasting time was longer than before, the maximum electricity output was still limited.

Figure 18. The electrical output of co-culture system with fermentation bacteria added 8 h later into the system

MFC device—simple, convenient and high efficiency

References

[1] Tang Y J, Meadows A L, Keasling J D. A kinetic model describing Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 growth, substrate consumption, and product secretion.[J]. Biotechnology & Bioengineering, 2007, 96(1):125–133. [2] Feng X, Xu Y, Chen Y, et al. Integrating Flux Balance Analysis into Kinetic Models to Decipher the Dynamic Metabolism of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1[J]. Plos Computational Biology, 2011, 8(2):e1002376-e1002376. [3] Highly efficient L-lactate production using engineered Escherichia coli with dissimilar temperature optima for L-lactate formation and cell growth. [4] Liu H, Kang J, Qi Q, et al. Production of lactate in Escherichia coli by redox regulation genetically and physiologically.[J]. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2011, 164(2):162-169. [5] Zhu J, Shimizu K, Zhu J, et al. Effect of a single-gene knockout on the metabolic regulation in Escherichia coli for D-lactate production under microaerobic condition[J]. Metabolic Engineering, 2005, 7(2):104–115. [6] Thomas E, Kuhlman, Edward C, Cox. Site-specific chromosomal integration of large synthetic constructs.[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2010, 38(38). [7] Lin Z, Xu Z, Li Y, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of riboflavin[J]. Microbial Cell Factories, 2014, 13(1):1-12. [8] Wang X, Tao L, Wang H, et al. Improving mediated electron transport in anodic bioelectrocatalysis[J]. Chemical Communications, 2015. [9] Okamoto A, Nakamura R, Nealson K H, et al. Bound Flavin Model Suggests Similar Electron‐Transfer Mechanisms in Shewanella and Geobacter[J]. Chemelectrochem, 2014, 1(11):1808-1812. [10] Yang Y, Ding Y, Hu Y, et al. Enhancing Bidirectional Electron Transfer of Shewanella oneidensis by a Synthetic Flavin Pathway[J]. Acs Synthetic Biology, 2015. [11]Shi S, Chen T, Zhang Z, et al. Transcriptome analysis guided metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for riboflavin production[J]. Metabolic engineering, 2009, 11(4): 243-252. [12] Song H, Ding M Z, Jia X Q, et al. Synthetic microbial consortia: from systematic analysis to construction and applications[J]. Chem.soc.rev, 2014, 43(20):6954-6981.

E-mail: ggjyliuyue@gmail.com |Address: Building No.20, No.92 Weijin road, Tianjin University, China | Zip-cod: 300072

Copyright 2015@TJU iGEM Team